JEAN GEBSER

THE EVER-PRESENT ORIGIN

Authorized Translation by Noel Barstad with Algis Mickunas

PART ONE: Foundations of the Aperspectival World

A Contribution to the History of the Awakening of Consciousness

PART TWO: Manifestations of the Aperspectival World

An Attempt at the Concretion of the Spiritual

Ohio University Press

Athens

Ohio University Press, Athens, Ohio 45701

Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data

Gebser, Jean.

The ever-present origin.

Translation of: Ursprung and Gegenwart.

Includes bibliographical references and indexes.

Contents: Foundations of the aperspectival world : a contribution to the history of the awakening of consciousness—Manifestations of the aperspectival world : an attempt at the concretion of the spiritual.

1. Civilization—History. 2. Civilization—Philosophy. 3. Intellectual life—History. 4. Civilization, Occidental. I. Title.

CB83.G413 1984 901 83-2475

ISBN 0-8214-0219-6

ISBN 0-8214-0769-4 pbk.

Ohio University Press books are printed on acid-free paper ∞

12 11 10 12 11 10

Ursprung und Gegenwart © 1949 and 1953

by Deutsche Verlags-Anstalt GmbH, Stuttgart

English translation © 1985 by Noel Barstad

Printed in the United States of America

All rights reserved.

Contents

Translator’s Preface

In memoriam Jean Gebser by Jean Keckeis

List of Illustrations

Preface

From the Preface to the Second Edition

From the Preface to the Paperbound Edition

PART ONE: FOUNDATIONS OF THE APERSPECTIVAL WORLD A CONTRIBUTION TO THE HISTORY OF THE AWAKENING OF CONSCIOUSNESS

Editorial Note regarding the Annotations

Chapter One: Fundamental Considerations

Origin and the Present 1—Mutations of Consciousness 2—Aperspectivity and the Whole 3—Individualism and Collectivism 3—The Possibility of a New Awareness 4—The Example of the Aztecs and the Spaniards 5—The Transparency of the World 6—Methodology and Diaphaneity 7

Chapter Two: The Three European Worlds

1. The Unperspectival World

Perspective and Space 9—Spacelessness Synonymous with Egolessness; Cavern and Dolmen; Egypt and Greece 10

2. The Perspectival World

The Development of Perspective since Giotto 11—Petrarch’s Discovery of Landscape 12—Petrarch’s Letter about his Ascent of Mont Ventoux 13—The History of Perspective as an Expression of the Awakening Awareness of Space 16—Eight and Night 17—Psychic Chain Reactions 17—Positive and Negative Effects of Perspectivation 18—The Realization of Perspective in Thought by Leonardo da Vinci 19—Space: the Theme of the Renaissance 21—The Age of Segmentation after 1500 A.D.; Isolation and Collectivism 22—Time Anxiety and the Flight from Time Resulting from the Conquest of Space 22

3. The Aperspectival World

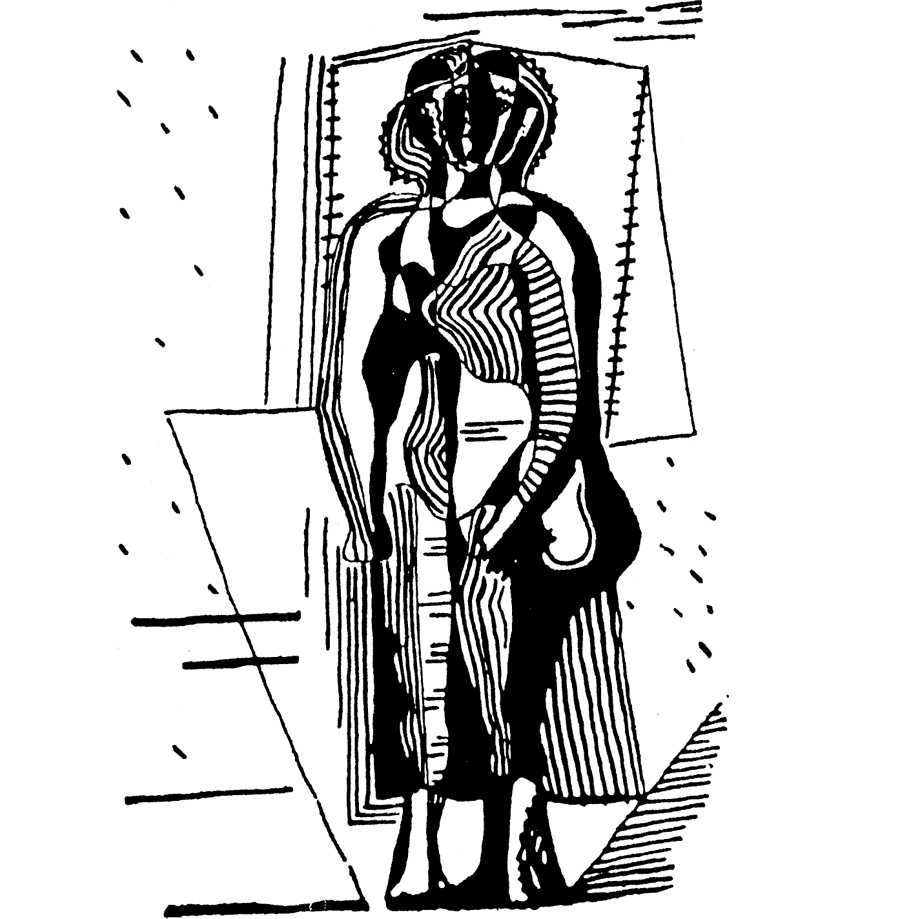

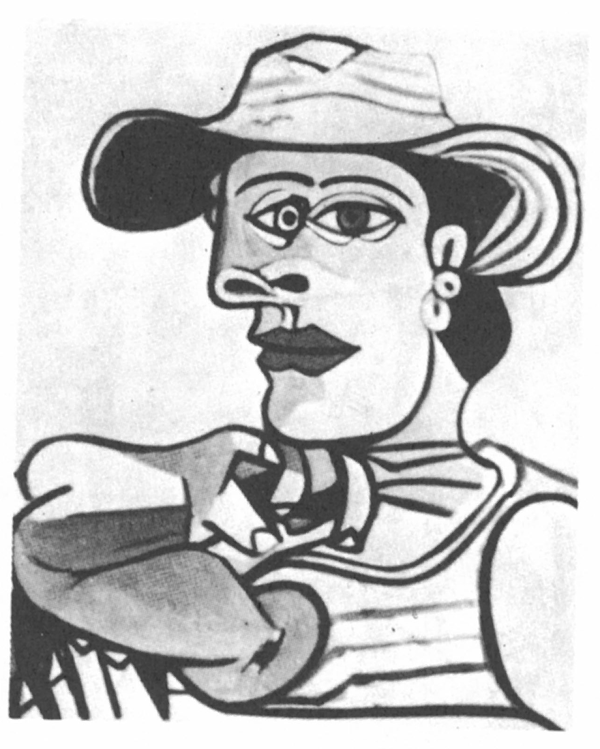

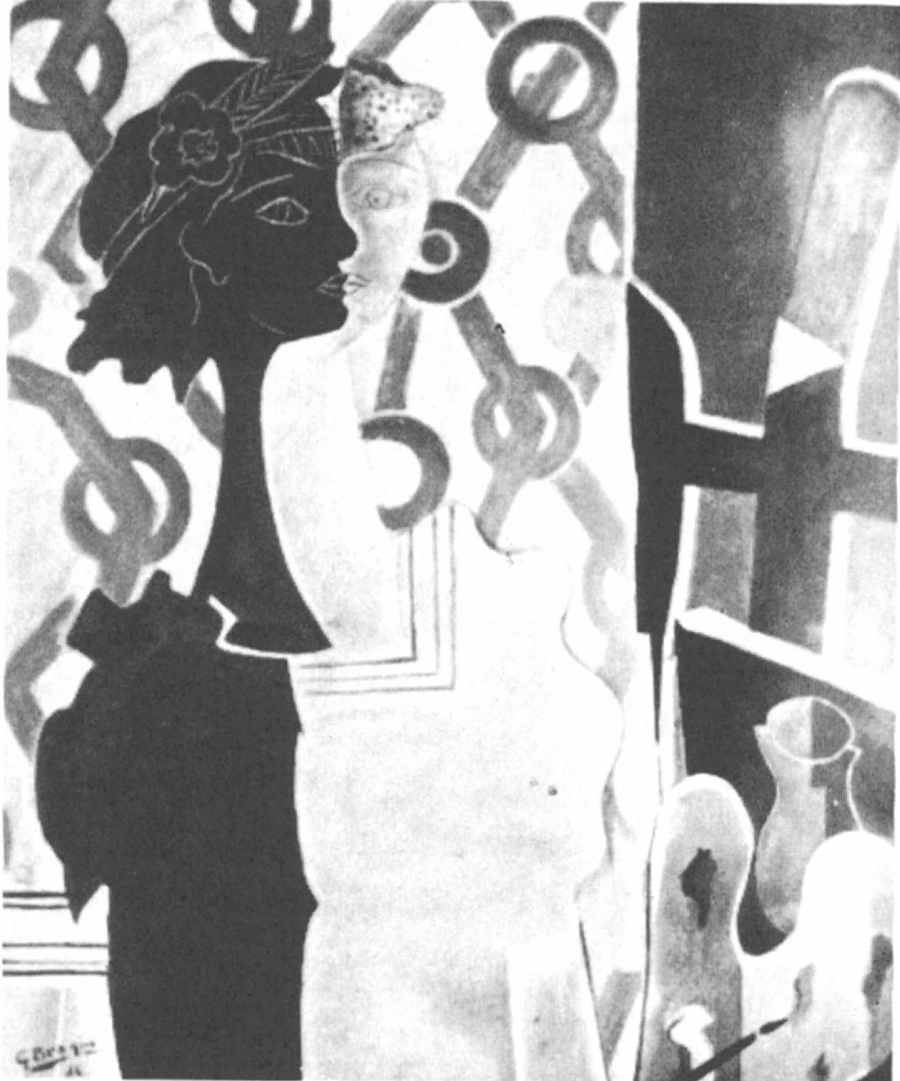

Aperspectivity and Integrality 24—The Moment and the Present; the Concretion of Time in the Work of Picasso and Braque as a Temporic Endeavor 24—The Inflation of Time in Surrealism 26—The Integral Character of the Temporic Portrait 27

Chapter Three: The Four Mutations of Consciousness

1. On Evolution, Development, and Mutation

The “New” invariably “above” the previous Reality 36—The Idea of Evolution since Duns Scotus and Vico 37—Mutation instead of Progress; Plus and Minus Mutations 38—The Theme of Mutations in Contemporary Research 39—Mutation and Development 40—Psychic Inflation as a Threat to Presentiation 43

2. Origin or the Archaic Structure

Origin and Beginning 43—Identity and Androgyny; Syncretisms and Encyclopedias; Wisdom and Knowledge; Man without Dreams 44—The Archaic Identity of Man and Universe 45

3. The Magic Structure

The One-dimensionality of the Magic World 45—Magic pars pro toto 46—The Cavern: Magic “Space”; The Five Characteristics of Magic Man 48—Magic Merging 49—The Aura; Mouthlessness 55—Magic: Doing without Consciousness 60—The Ear: the Magic Organ 60

4. The Mythical Structure

Extrication from Vegetative Nature and the Awakening Awareness of the Soul 61—Myth as Silence and Speech 64—Mythologemes of Awakening Consciousness 69—The Role of Wrath in the Bhagavadgita and the Iliad; “Am Odysseus” 71—The Great “Nekyia” Accounts 72—Life as a Dream (Chuang Tzu, Sophocles, Calderon, Shakespeare, Novalis, Virginia Woolf); the Mythologeme of the Birth of Athena 72

5. The Mental Structure

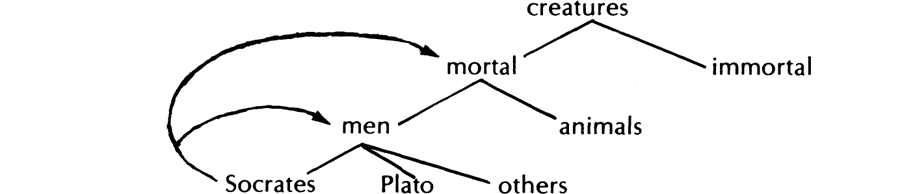

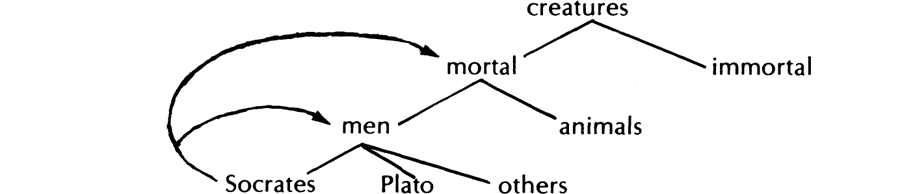

Ratio and Menis 74—Disruption of the Mythic Circle by Directed Thought 75—The Etymological Roots of the Mental Structure 76—The Archaic Smile; the Direction of Writing as an Expression of Awakening Consciousness 78—Law, Right, and Direction 79—On the “Law of the Earth”; The Simultaneity of the Awakening of Consciousness in China, India, and Greece 79—The Dionysia and Drama; Person and Mask; The Individual and the Chorus 81—The Orphic Tablets 82—The Mythical Connotative Abundance of Words and Initial Ontological Statements 83—Mythologeme and Philosopheme 84—The Riannodamento; the Consequential Identification of Right and Correct; Polarity and Duality 85—Trias and Trinity; Ancestor Worship and Child Worship 86—Origin of the Symbol 87—Symbol, Allegory, and Formula 88—Quantification, Sectorization, and Atomization; the Integration of the Soul 89—Buddhism and Christianity; The Northwest Shift of Centers of Culture 90—The Theory of Projection in Plutarch; relegio and religio 91—St. Augustine 92—The Riannodamento Completed 93—The Immoderation of the ratio 94—Preconditions for the Continuance of the Earth; the Three Axioms of Being 96

6. The Integral Structure

Traditionalists and Evolutionists 98—The Concretion of Time 99—Temporic Inceptions since Pontormo and Desargues 100

Chapter Four: Mutations as an Integral Phenomenon: an Intermediate Summary

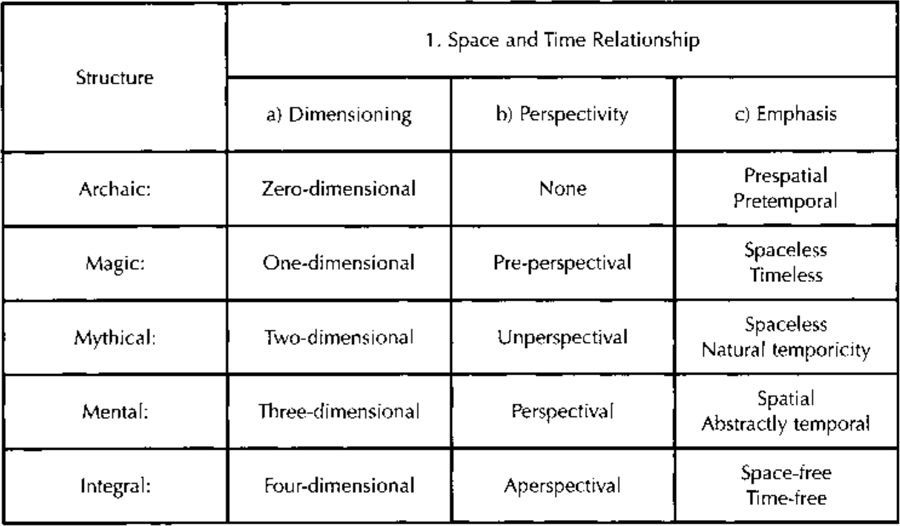

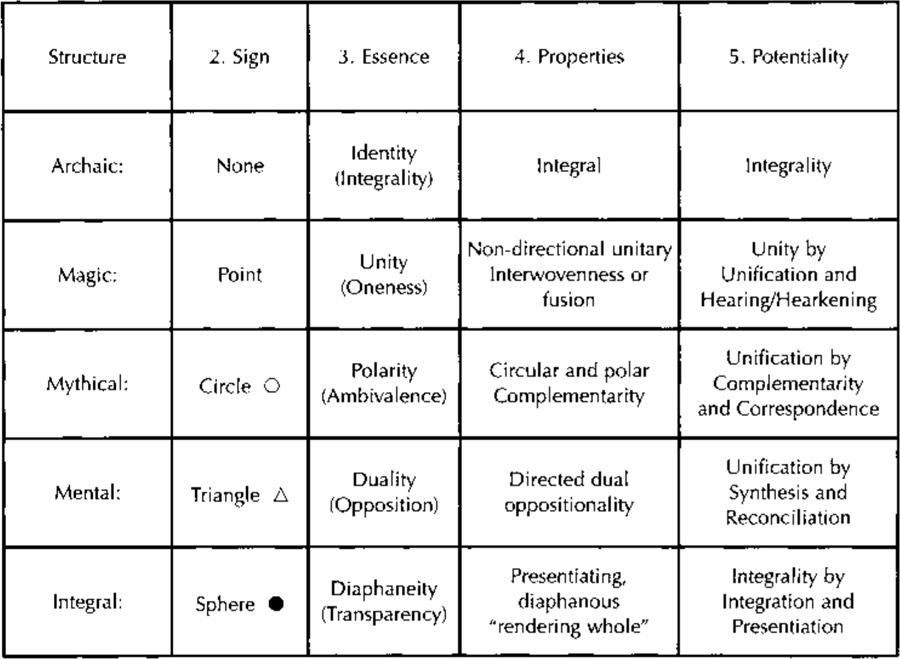

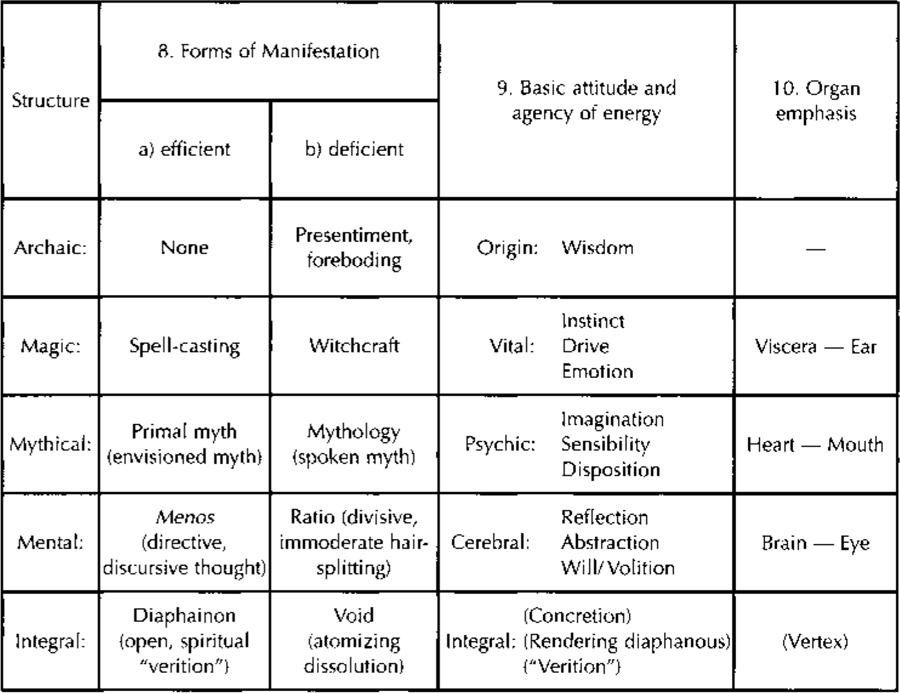

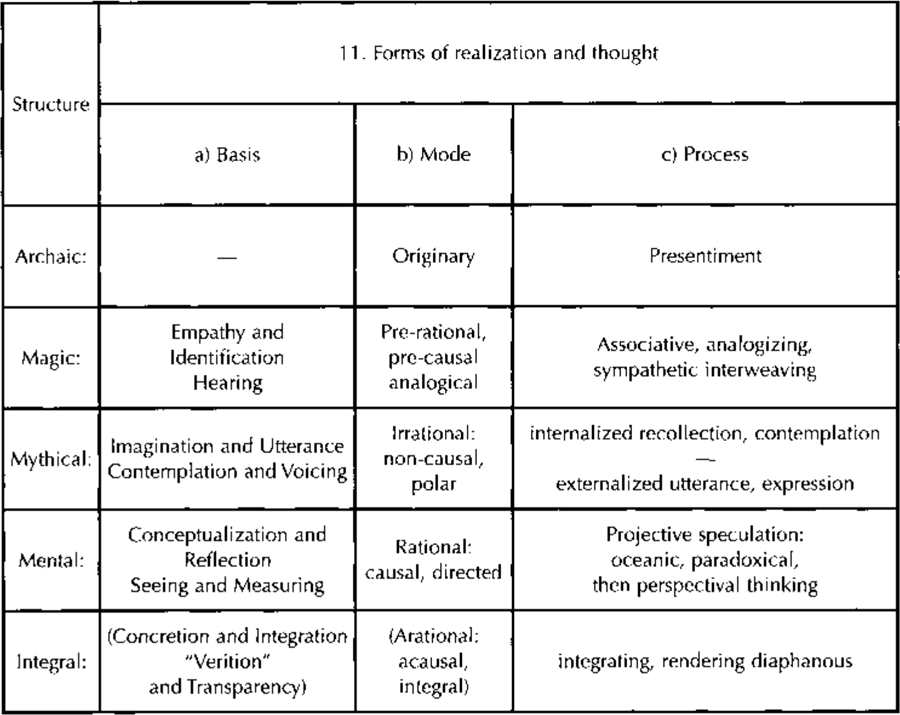

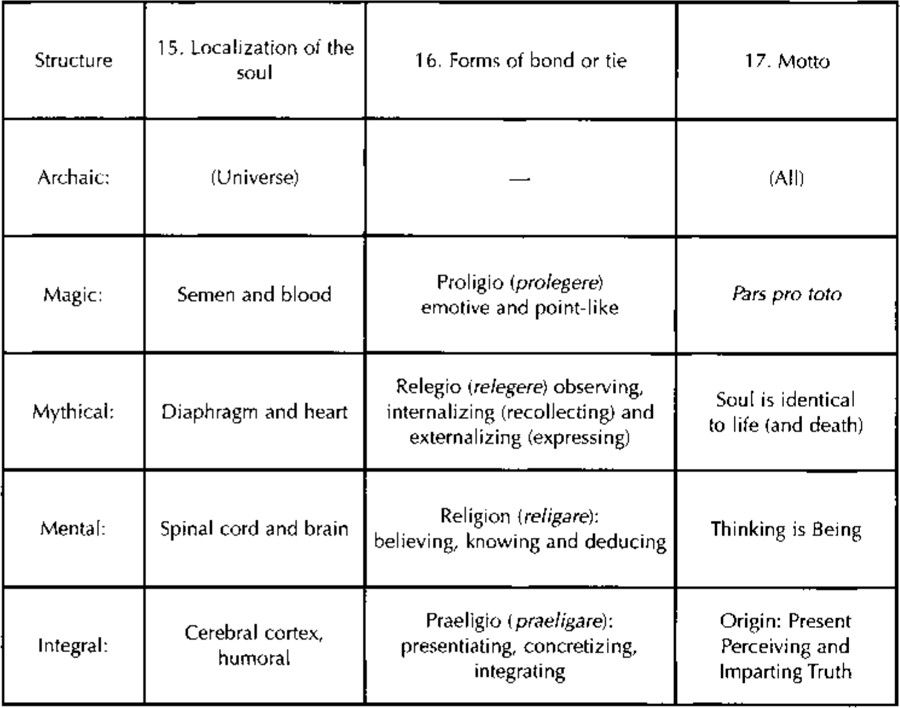

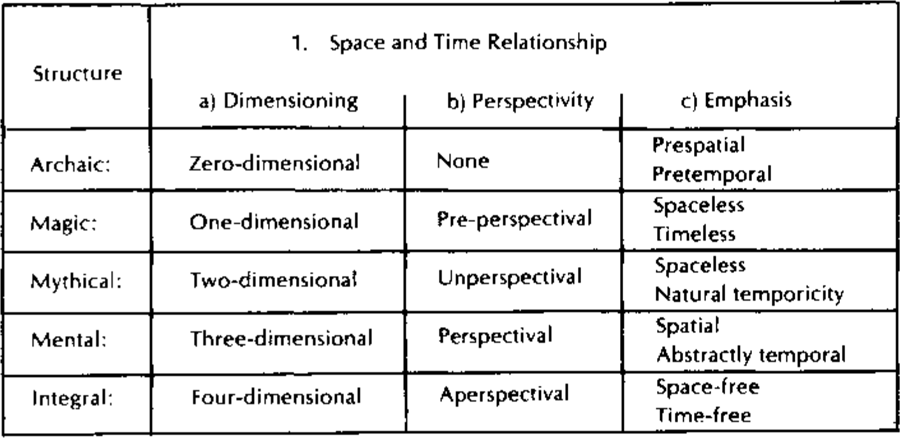

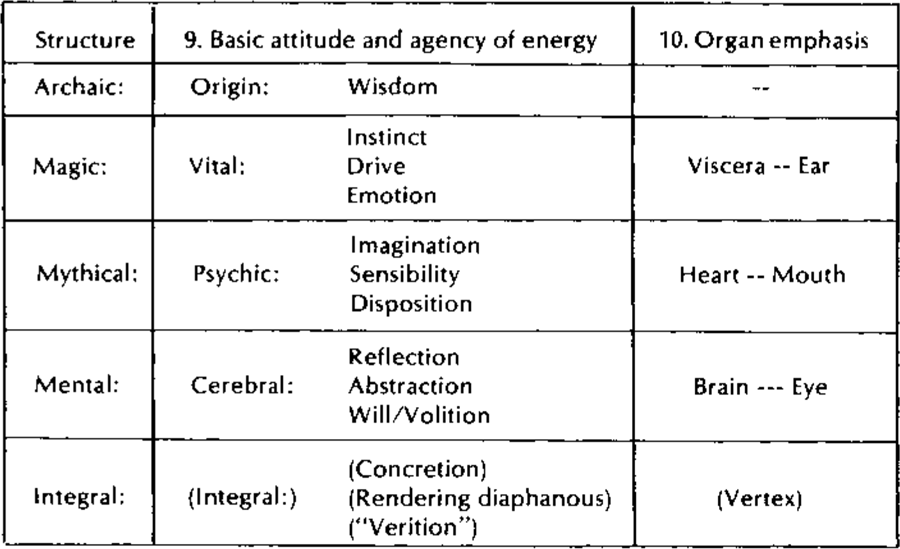

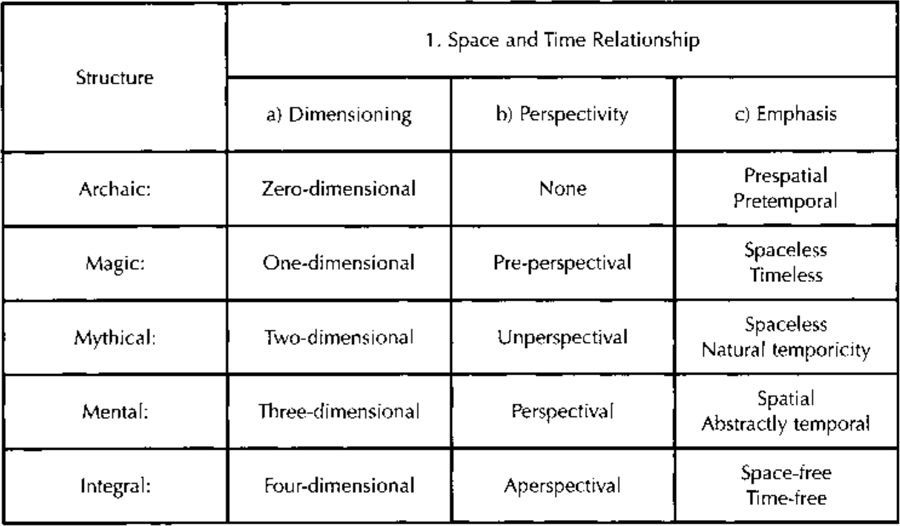

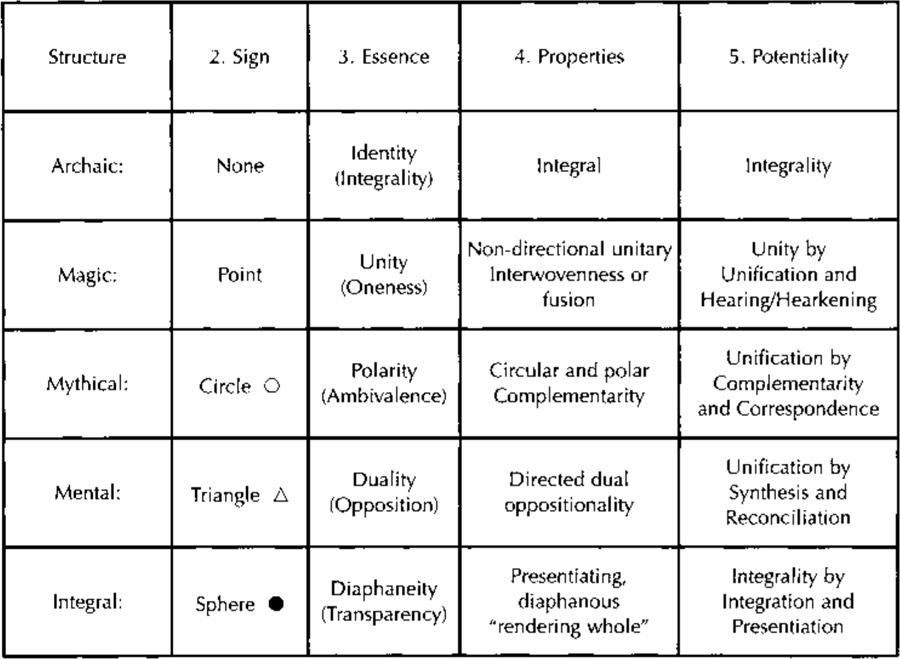

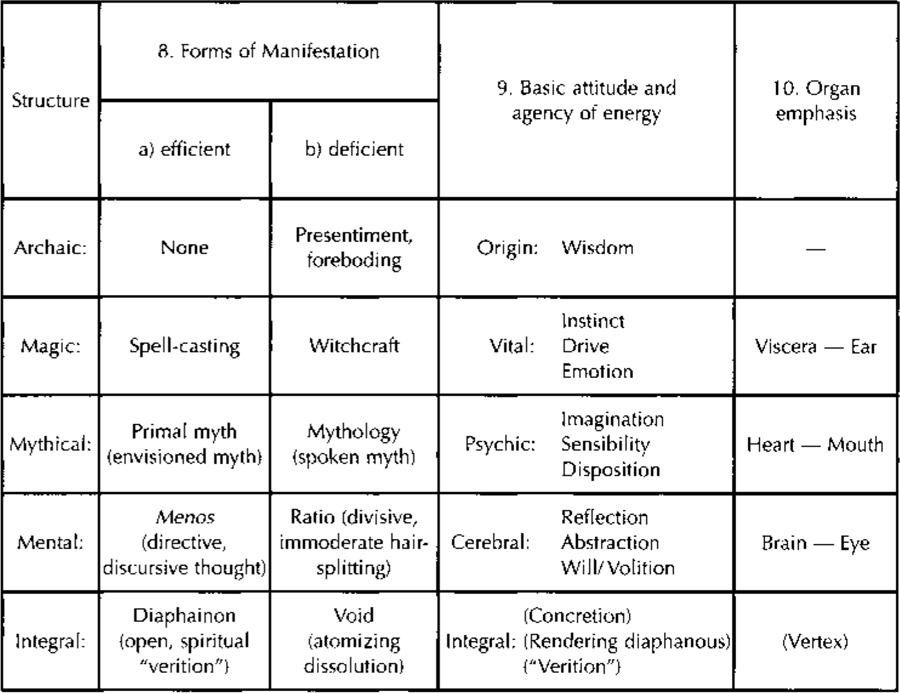

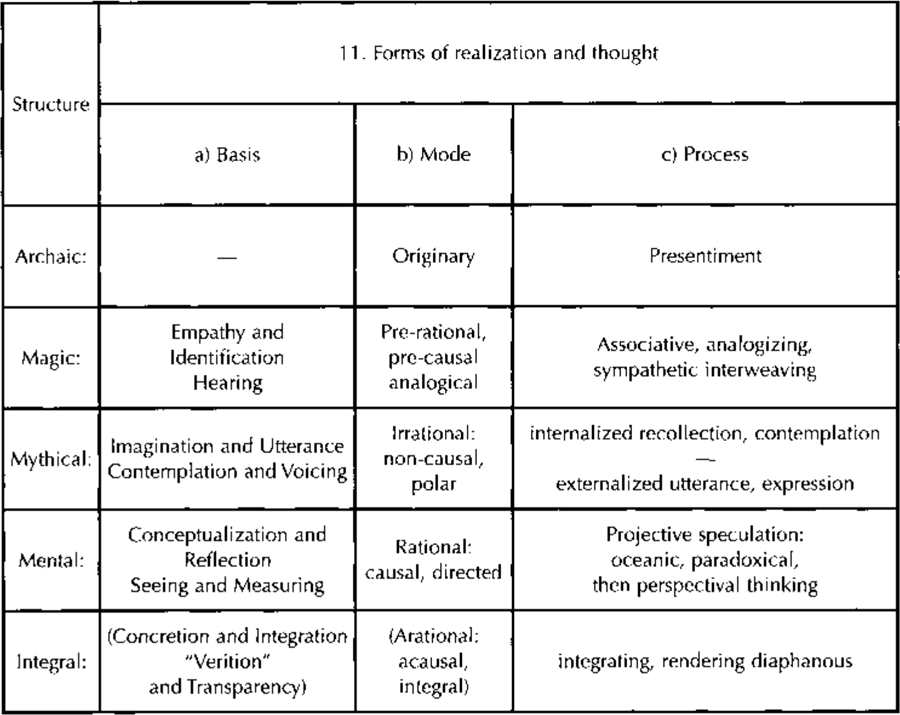

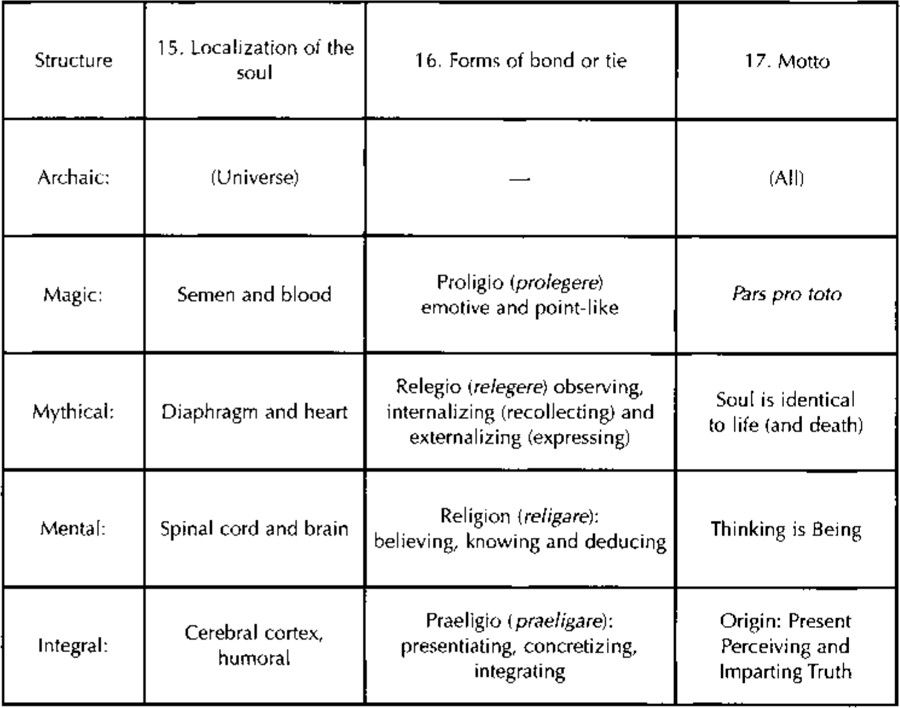

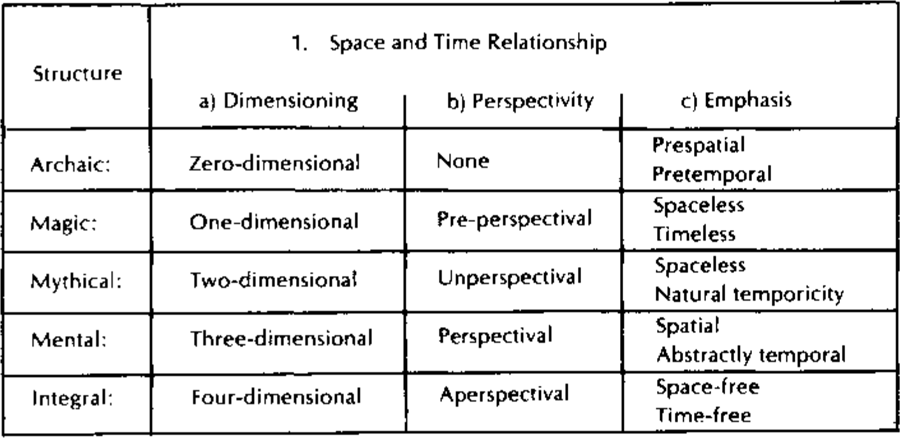

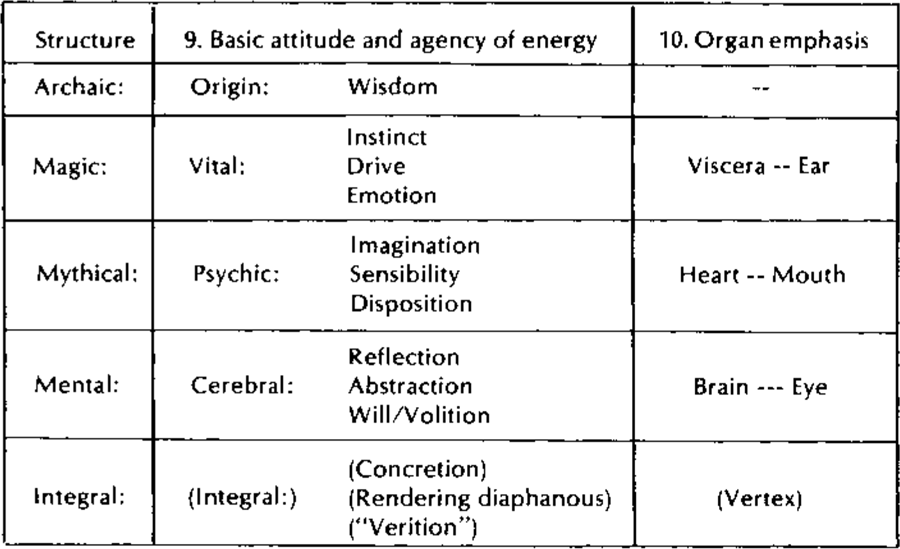

1. Cross-Sections through the Structures

The Interdependency of Dimensioning and Consciousness 117—The Diaphainon; The Signs and Essence of the Structures 118—The Presence of Origin; the Symmetry of the Mutations 120

2. A Digression on the Unity of Primal Words

An Integral Examination of Language 123—The Bivalence of the Roots; the Root Kinship of Cavern and Brightness 126—Mirror Roots 127—The Root Kinship of Deed and Death 128—The Word “All” 129

3. A Provisional Statement of Account: Measure and Mass

The Four Symmetries of the Mutations 129—Transcendence as Mere Spatial Extension 131—Technology as a Material-physical Projection 132—The Anxiety and Cul-de-Sac of our Day 133—The Itself 134—Mystery and Destiny; The “Way” of Mankind 136—Our Egoconsciousness 137—The Realization of Death 138 f.—A Glance at a New “Landscape” 140—The Possibilities of a New Bearing and Attitude 140

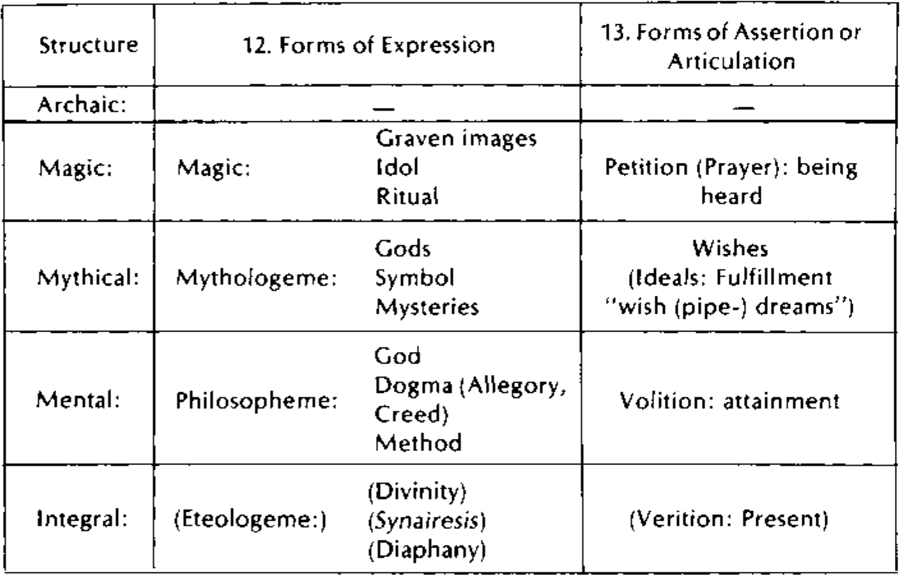

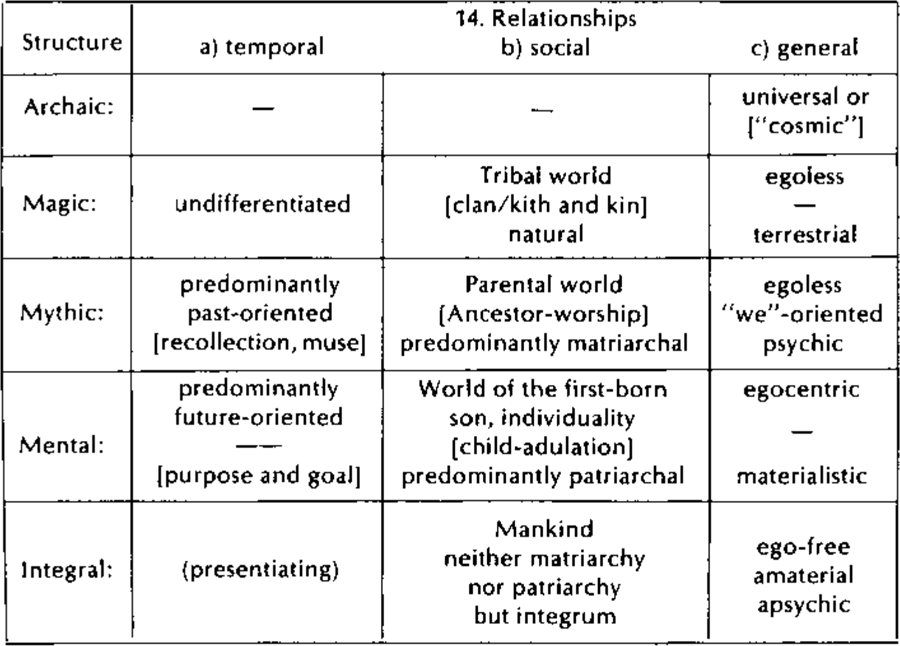

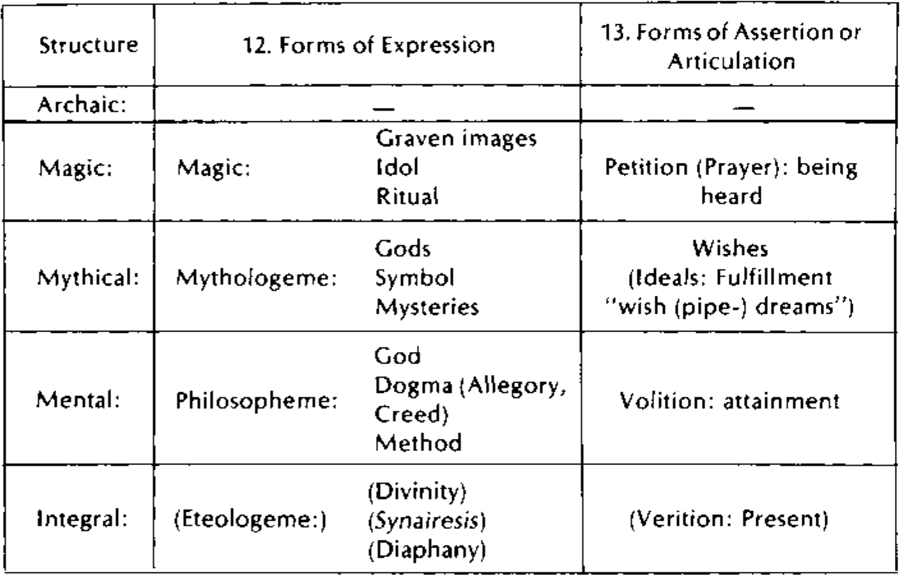

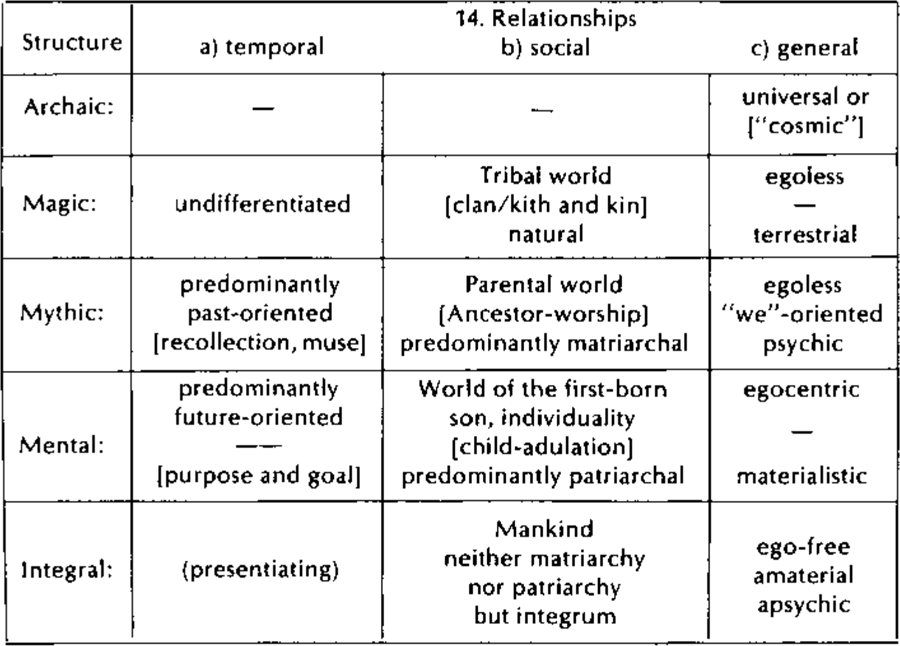

4. The Unique Character of the Structures (Additional Cross Sections)

Method and Diaphany 143—Magic “Receptivity by the Ear” 145—The Mythical Language of the Heart 145—Irrationality, Rationality, Arationality 147—Idols, Gods, God; Ritual, Mysteries, Methods 147—The Decline and Fall of Matriarchy 149—Patriarchy 150

5. Concluding Summary: Man as the Integrality of His Mutations

Deliberation and Clarification 152—The Deficient Effects of the Structures in our Time 153

Chapter Five: The Space-Time Constitution of the Structures

1. The Space-Timelessness of the Magic Structure The Magic Role of Prayer and the Miraculous Healings of Lourdes 163

2. The Temporicity of the Mythical Structure

The Polarity Principle 166—The Movement of Temporicity 166—The Circularity of Mythical Imagery 167—The Mythologeme of Kronos 168—Kronos as an Image of the Nocturnal World 168—The Emergence of Temporicity from Timelessness 170—The Significance of the Root Sounds K, L, and R 171 f.—On the Mirror Roots 172

3. The Spatial Emphasis of the Mental Structure

The Root of the Words meaning “Time”; Time as a Divider 173—The Kronos Sacrifice of Dais: the Emergence of Time from Temporicity 174—The Perversion of Time (The Divider is itself divided) and the Declassification of Time in Western Philosophy 178—Thought as a Spatial Process, and the Spatial Emphasis of the Mental Structure 180—The Beginning of Change in Space 181

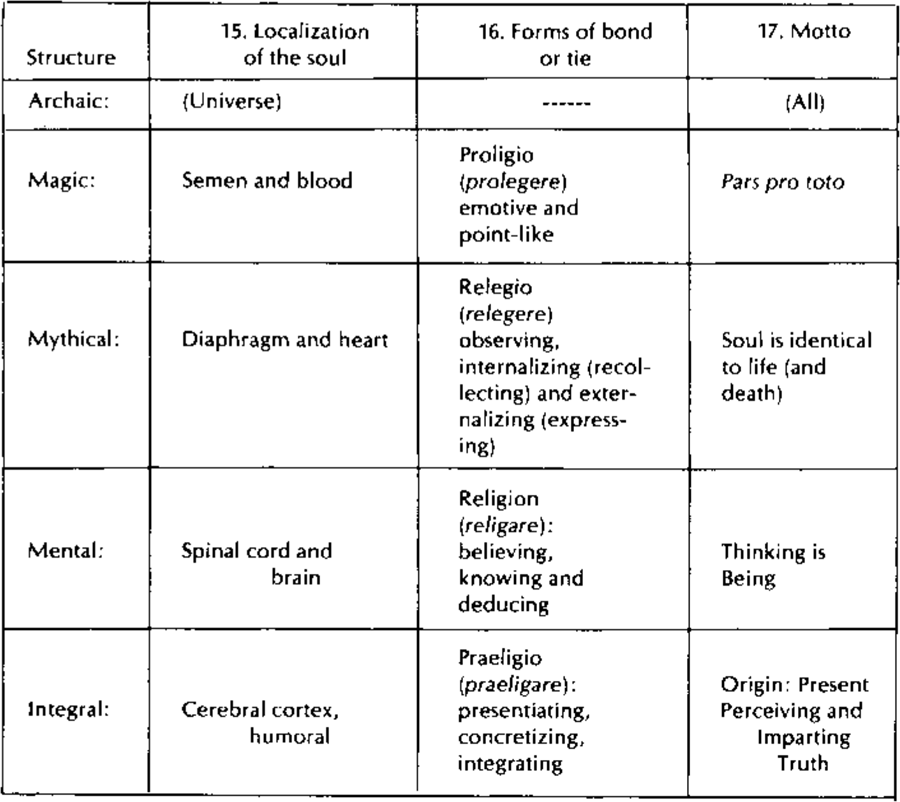

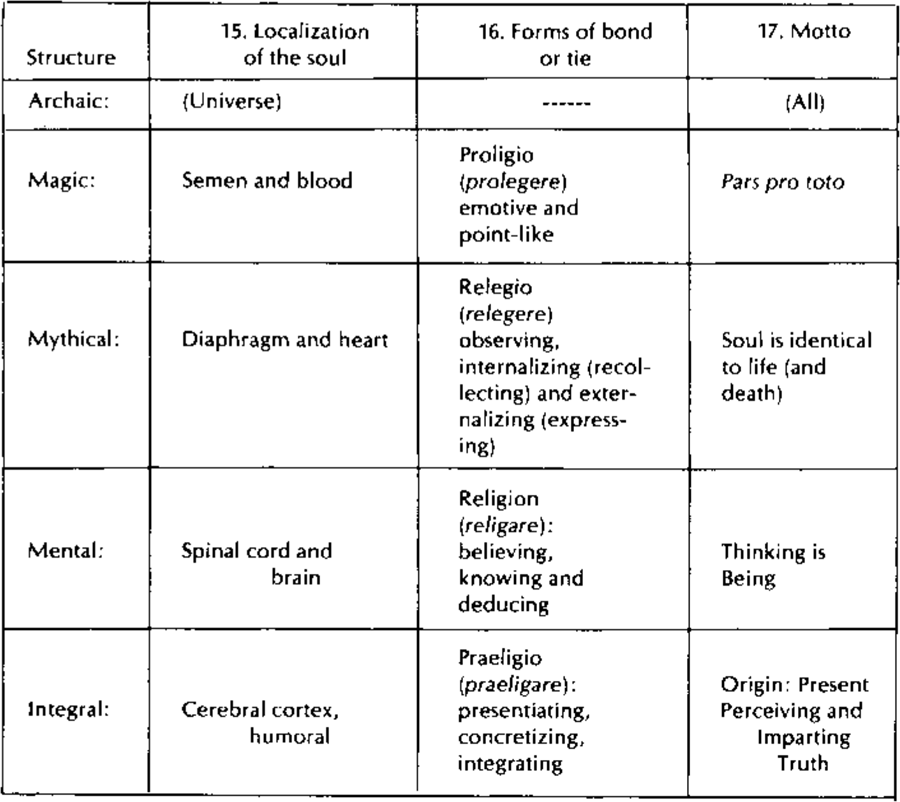

Chapter Six: On the History of the Phenomena of Soul and Spirit

1. Methodological Considerations

Soul and Time, Thinking and Space 189—The Apsychic and Amaterial Possibility of World 189—On the “Representationality” of the Unfathomable Psyche 189 f.

2. The Numinosum, Mana, and the Plurality of Souls

Previous Historical Theories 191—History and the Numinosum 193—Mana 194—The Origin of the Concept of Soul 194—Souls and the Soul; Spirits and the Spirit 197—Life and Death as an Integral Present 199—The Numinosum as a Magic Experience 201 f.—The Relocation of Numinous Provocation 202—The Ability of Human Resonance 203—Consciousness 203—Erroneous Conclusions of Postulating the “Unconscious” 204—Intensification, not Expansion of Consciousness; Psychic Potencies and the Centering of the Ego 205

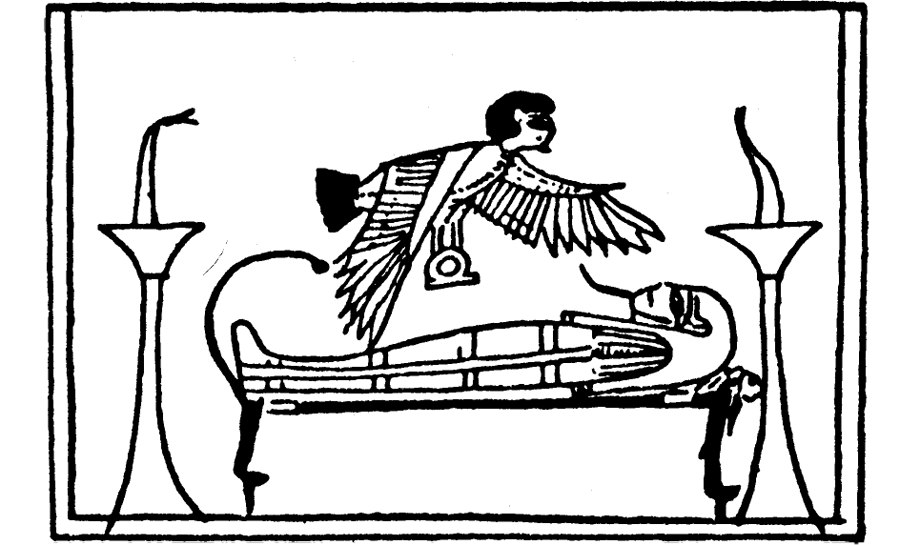

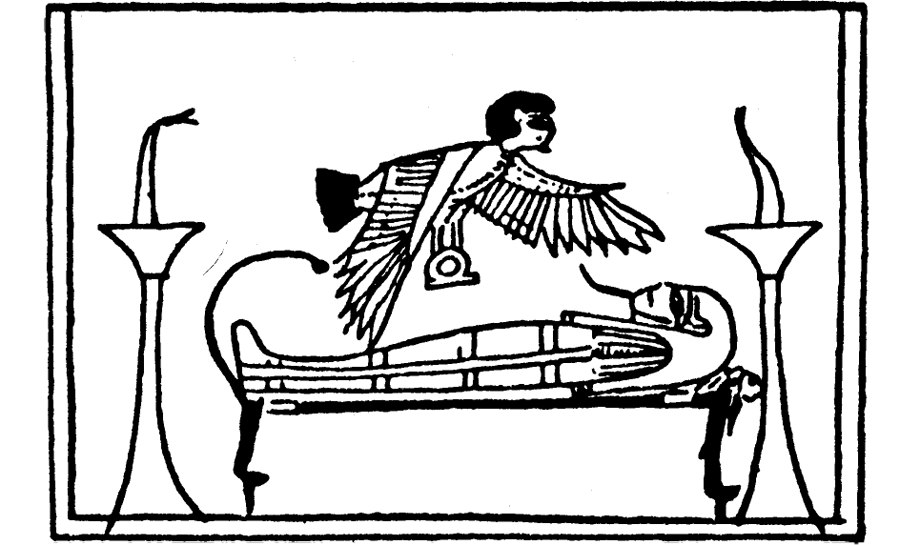

3. The Soul’s Death-Pole

The Symbolism of the Death-Soul 206—The Egyptian Soul-Bird and the Angels 207—Sirens and Muses; Death-Soul and Death Instinct—The Mythologization of Psychology and Physics 209—The Egyptian Sail as a Symbol for the Soul; The Lunar Character of the Soul in the Vedic, Egyptian, and Greek Traditions 210—The Ambivalence of Each Pole of the Soul 214

4. The Soul’s Life-Pole

The Symbolism of the Life-Pole 216—The Water Symbolism for the Life Pole 217—Water as a Trauma of Mankind 219

5. The Symbol of Soul

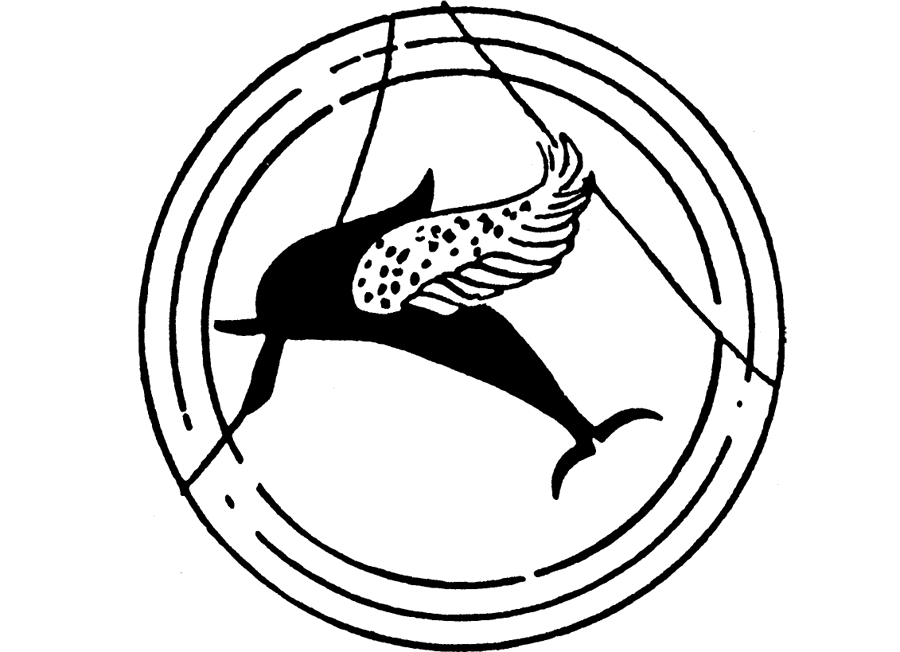

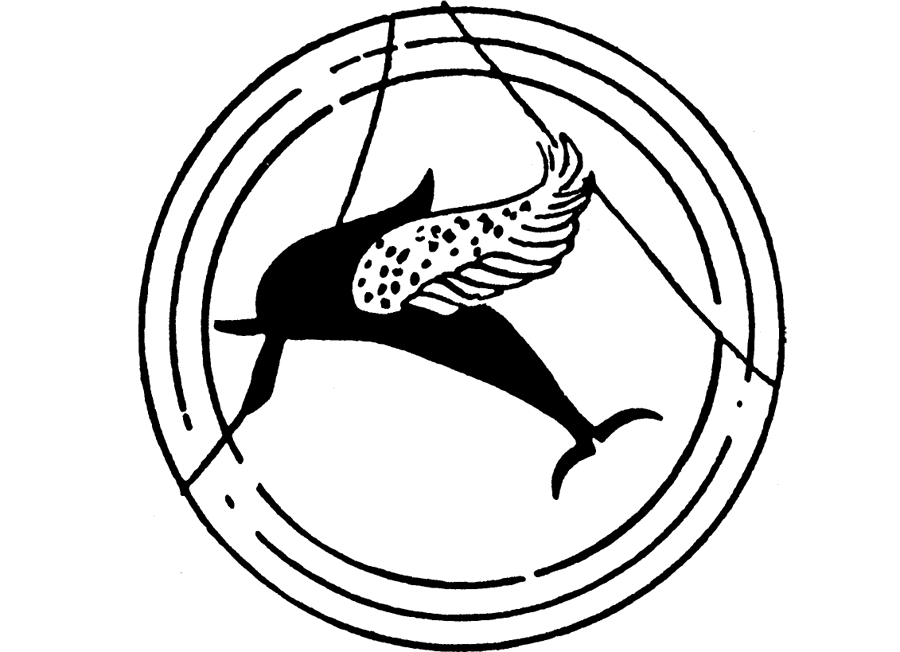

The Chinese T’ai-Ki; the Pre-Tellurian Origin of Primal Symbols; Estimative and Living Knowledge 220—Life and Death are not Antithetical 224—The Winged Dolphin as a Greek Symbol for Soul 225—The Journeys to Hades 226—The Living Knowledge of the Soul 226

6. On the Symbolism of the Spirit

Souls and Spirits 229—Early Concepts of Spirit; the Symbolism of the Spirit 230—Spirit and Intellect 231—Spirits, Spirit, and the Spiritual 232

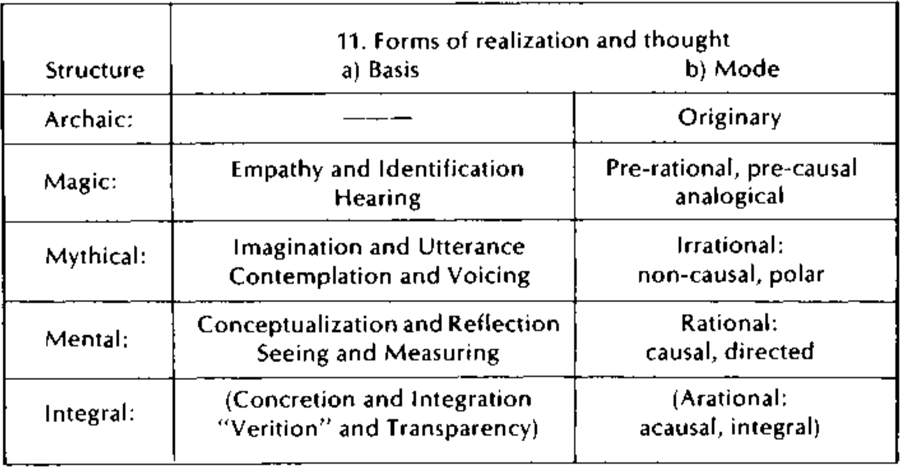

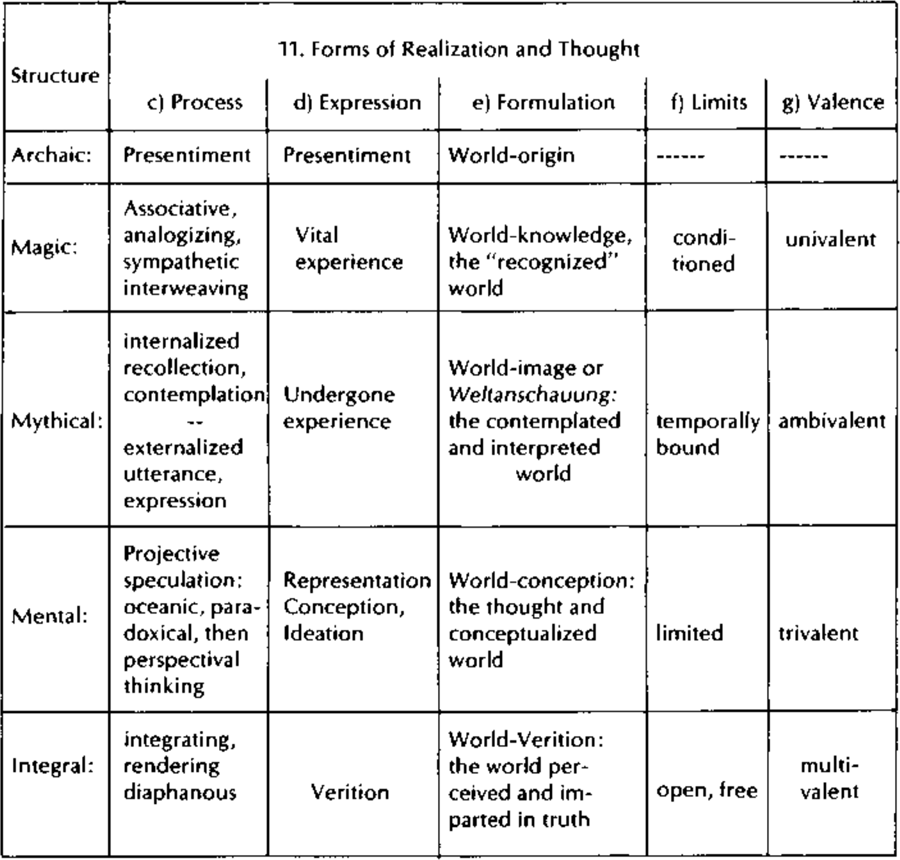

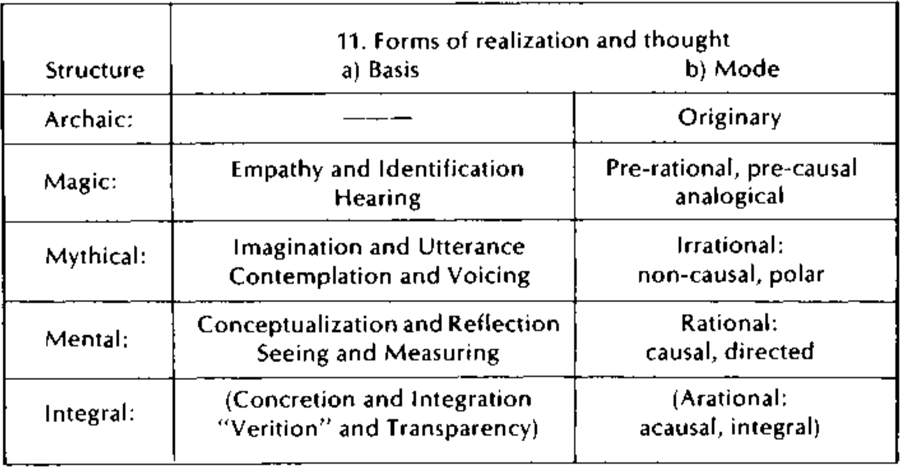

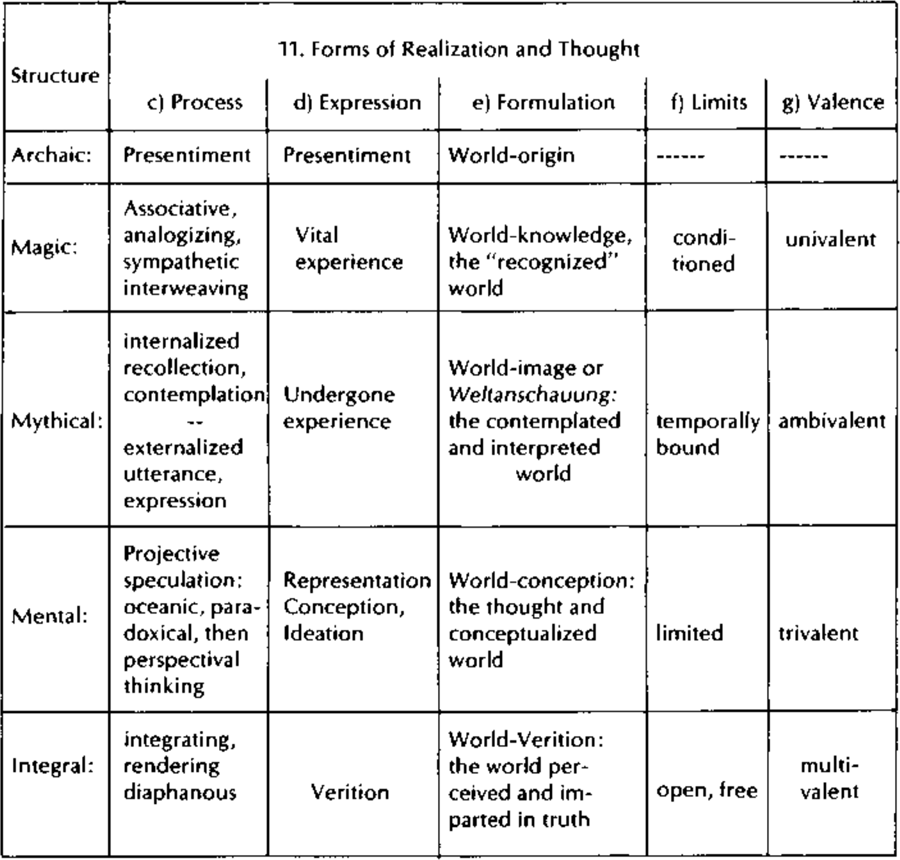

Chapter Seven: The Previous Forms of Realization and Thought

1. Dimensioning and Realization

The Dependency of Realization on the Dimensioning of the Particular Structure 249—The Constitutional Differences of the Individual Forms of Realization 250

2. Vital Experiencing and Undergone or Psychic Experience

Vital Experiencing as a Magic Form of Realization 250—Undergone Experience as a Mythical Form of Realization 251

3. Oceanic Thinking

Circular Thinking; Oceanos and the World as an Island 252—Oceanic Thinking 252

4. Perspectival Thinking

The Birth of Mental Thought 255—The Concept of Perspectivity 255 f.—The Visual Pyramid and the Conceptual Pyramid 256—The Spatiality of Thinking 258

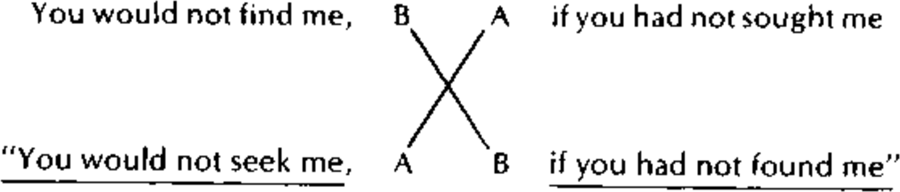

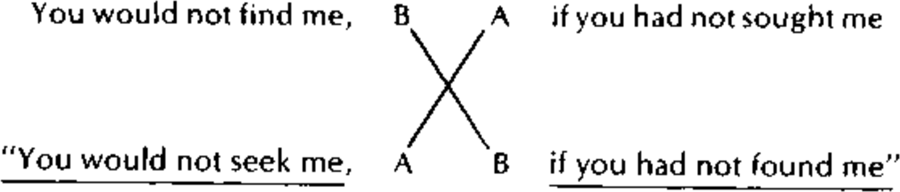

5. Paradoxical Thinking

Paradox 259—The Intersecting Parallels 260—Left-Right Inversion 261—The Awakening of the Left 262—Women’s Rights 262—Left Values in Contemporary Painting; Diaphany and Verition of the World 263

Chapter Eight: The Foundations of the Aperspectival World

1. The Ever-Present Origin (Complementing Cross Sections)

The Non-conceptual Nature of the Aperspectival World 267—The Perception and Impartation of Truth as Aperspectival Forms of Realization 268—Forms of Bond and Proligio; Praeligio; Origin as Present 271

2. Summation and Prospect

The Possibilities for a New Mutation 272—Superseding psychic and material Atomization; Mankind’s Itself-Consciousness 273—The Liberation from “Time:” Origin and Present 273

PART TWO: MANIFESTATIONS OF THE APERSPECTIVAL WORLD AN ATTEMPT AT THE CONCRETION OF THE SPIRITUAL

Author’s Comment

Interim Word

Chapter One: The Irruption of Time

1. The Awakening Consciousness of Freedom from Time

The Various Time-Forms 284—The Complexity of “Time” 285—Time as an Acategorical Magnitude; System and Systasis 286—The Revaluation of the Time Concept at the Outset of our Century 286—Time Anxiety as a Symptom of our Epoch 288—Time-Freedom 289

2. The Awakening Consciousness of Integrity or the Whole

Purely Spatial Reality 290—Europe’s Decisive Role 290—Three Examples 291—Preconditions for the Awakening Consciousness of the Whole 292

Chapter Two: The New Mutation

1. The Climate of the New Mutation

Mutational Periods as Times of Disruption 295—The Future in us and in the World 296—The Mistaken Anthropocentric Belief 299—Presence and Efficacy 300

2. The Theme of the New Mutation

How did the Steam Engine come to be discovered? 301—The Consolidation of Spatial Consciousness made possible the New Mutation 302—Time as an Intensity 304—Agricultural and Craft Cultures 305—The Loss of Nature and Culture 306—”Time,” the Theme of the New Mutation 306

3. The New Form of Statement

Hufeland’s “New Strength of Spirit” 307—The Manifestational Forms of Time; Temporal Things cannot be Spatially fixed 308—Philosopheme and Eteologeme; Systasis and Synairesis 309 f.

Chapter Three: The Nature of Creativity

1. Creativity as an Originary Phenomenon

The Inadequacy of the Psychological Explanation 313—Statements from the “Book of Changes” 314—“The Primal Depths of the Universe” 315

2. The Nature and Transformation of Poetry

The Significance of the “Muse” 317—The Muse, Musing, and “Must” 317—The Muse as a Divinity of the Well-springs, a Power of Life, and a Creative Force 318—The Siren (an Anti-Muse) and Rilke 320—The Individualization of Literature in Lyric Poetry 320—Hölderlin’s Decisive Step 323—The “Supersession of Time” by Hofmannsthal, and the “Taming of the Muses” by Baudelaire 324—Mallarmé’s “New Obligation” 325—Valéry’s “Extreme Self-Consciousness” 326—T. S. Eliot’s Rejection of the Muses and His Freedom from Ego 326 f.—Huxley and “Time Must have a Stop” 328—Eluard and Hagen 328—Today’s Altered Creative Relationship as a Demonstration of the New Structure of Consciousness 330

Chapter Four: The New Concepts

1. Inceptions of the New Consciousness

The Spiritual Inception; The Physical Inception 335—Man is Predicated; The New Dogma of Mary 339

2. The Fourth Dimension

The Fourth Dimension is Time-Freedom 340—N. Hartmann’s “Dimensional Categories”; The Non-Euclidian Geometry of Gauss 341—The History of the Fourth Dimension; Einstein; The Supersensory as a Fourth Dimension 342—The Four-Fold Discovery of Non-Euclidian Geometry; Gauss and Petrarch 343—Lambert’s “Imaginary Sphere” 345—The Magic Adaptation of the Fourth Dimension 348—The Mythical Adaptation 349—The Mental Adaptation 351—The “Queen of the Sciences” 354—On the Essence of Time-Freedom 355

3. Temporics

Temporics: The Concern With Time 356—The Non-conceptual Nature of Time 358—Today’s Time Anxiety 359—The Overwhelming Effect of Time Repressed 359—Key Words of Aperspectivity 361

Chapter Five: Manifestations of the Aperspectival World (I): The Natural Sciences

1. Mathematics and Physics

Descartes and Desargues, Galileo and Newton; Speiser’s Set Theory and Hilbert’s System of Axioms 368—The End of the Mechanistic World-View of Classical Physics 370—The Theme of Time in Physics; The Quantum of Action 371—Heisenberg’s Law; the Age of the Universe 373—Heisenberg’s “Paradoxes of the Time Concept;” The Supersession of Dualism by the New Physics 374 f.—The (Arational) Non-Visualizable Nature of the Present-Day World-View in Physics 376

2. Biology

Time as a Quality 381—Vitalism and Totalitarianism 382—Portmann’s Recognition of the Spatio-Temporal Structure of all Forms of Life 382—The Supersession of Dualism in Biology 384—Its Emphasis on Interconnections instead of Divisions; The Arational Perception of Life 385

Chapter Six: Manifestations of the Aperspectival World (II): The Sciences of the Mind

1. Psychology

The Announcement of God’s Death; Faust’s Journey into “The Void” and the Discovery of the Layers of the Earth and the Soul 393—Endeavors to Grasp the Non-Spatial or Psychic Phenomena 394—Time in the Course of Dream Events (Freud), and as “Psychic Energy” (Jung)—The Supersession of Dualism by Jung’s Theories of Individuation and Quaternity 397—The Dangers of a Psychologized Four-dimensionality 398—The Visible Manifestation of Arational Time-Freedom; Jung’s “Archetypes” 399

2. Philosophy

Heidegger’s Eschatological Mood 402—The Incorporation of “Time” as a Proper Element into Philosophical Thought; Pascal and Guardini 404—Work and Property: Time and Space; Bergson’s “Time and Freedom” 405—Husserl’s “Time Constitution” 406—Rationality’s Admission of Inadequacy; Reichenbach’s “Three Valued Logic” 406—”Open Philosophy” 407—The Supersession of Immanence and Transcendence by Simmel and Szilasi 408—The Turn Toward the Whole and Toward Diaphaneity 409—The “Sphere of Being” 411—The Self-Supersession of Philosophy 411

Chapter Seven: Manifestations of the Aperspectival World (III): The Social Sciences

1. Jurisprudence

Custom and Law 418—Montesquieu’s Maxim for Mankind; The Consideration of the Time Factor in the New Jurisprudence 419—The Mastery of Prerational and Irrational Components of Justice (H. Marti)—The New Right to Work at the Expense of Property 421—The Super-session of Dualism in Jurisprudence (W. F. Bürgi and Adolf Arndt)—Tendencies toward Arationality in “Open Justice” 424

2. Sociology and Economics

Mankind’s Descent to Hell? 424—The Consideration of the Time Factor; Marxism on a Sidetrack 426—The New Qualitative Estimation of Work (L. Preller and A. Lisowsky) 428—Time and Structure in Sociology (W. Tritsch) 429—The Supersession of Dualism by an Acceptance of Indeterminism: Marbach (Political Economics), Guardini and Brod (Sociology), and Lecomte du Noüy (Anthropology) 429—The Supersession of the Alternative: Individual vs. Collective 430—The Supersession of the Idea of a Linear Course of History by Toynbee and von Salis 432—The Role of Frobenius’ Theory of Cultural Spheres 432—The Consideration of Contexts instead of Systematization 433—Dempf’s “Integral Humanism” 434—The World’s Openness 435—Alfred Weber’s Indication of an “Extraspatio-temporal Understanding” 436—Indications of new Possibilities of Consciousness in Brain Research (Lecomte du Noüy and H. Spatz) 437

Chapter Eight: Manifestations of the Aperspectival World (IV): The Dual Sciences

The Existence of the Dual Sciences as an Aperspectival Manifestation; Quantum Biology 445—Psychosomatic Medicine 446—Parapsychology 448

Chapter Nine: Manifestations of the Aperspectival World (V): The Arts

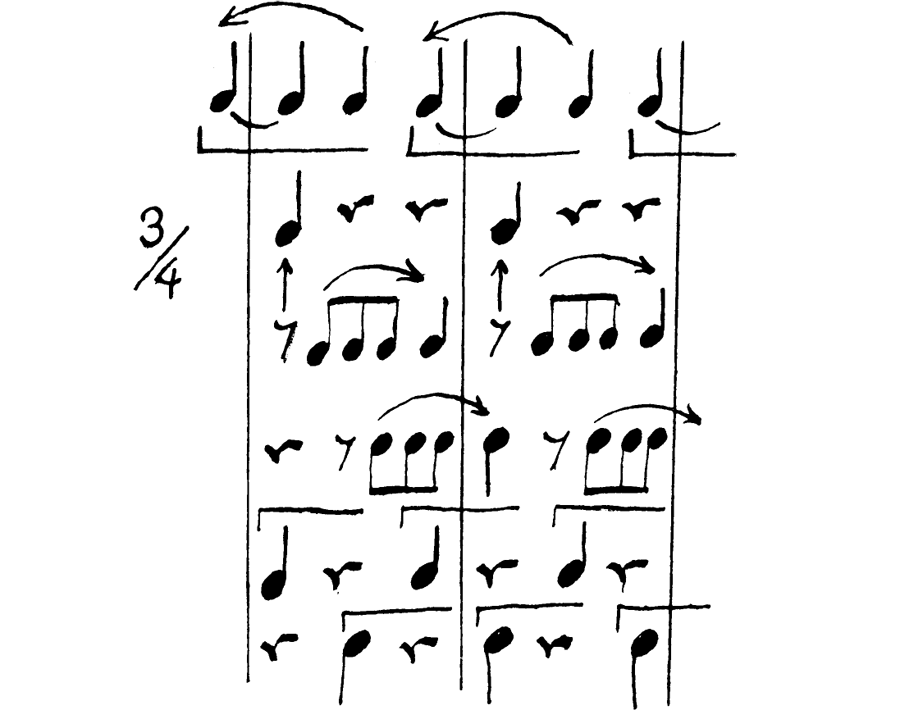

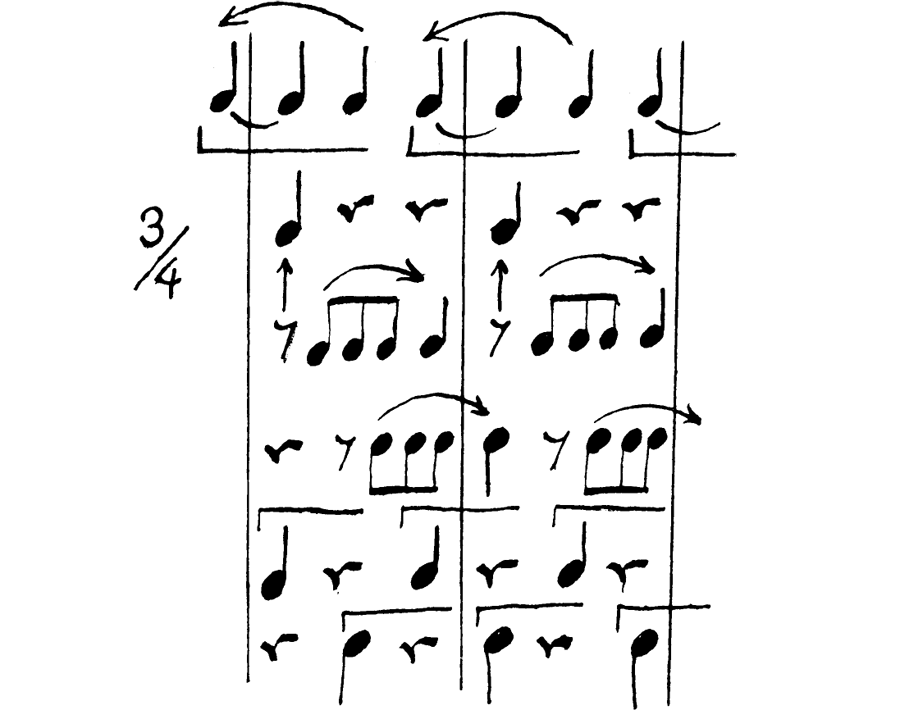

1. Music

Temporic Attempts in Music; Stravinsky’s Coming-to-Terms with Time 455—Busoni; Křenek’s New Valuation of Time 456—The Super-session of the Major-Minor Dualism 458—Liszt, Debussy and “Open Music” 459—Music’s Attempt to Realize Arationality 460—Pfrogner’s Conception of a Four-dimensional Music 461—The “Spiritualization of Music” 462—Debussy’s “Spherical Tonality” 463

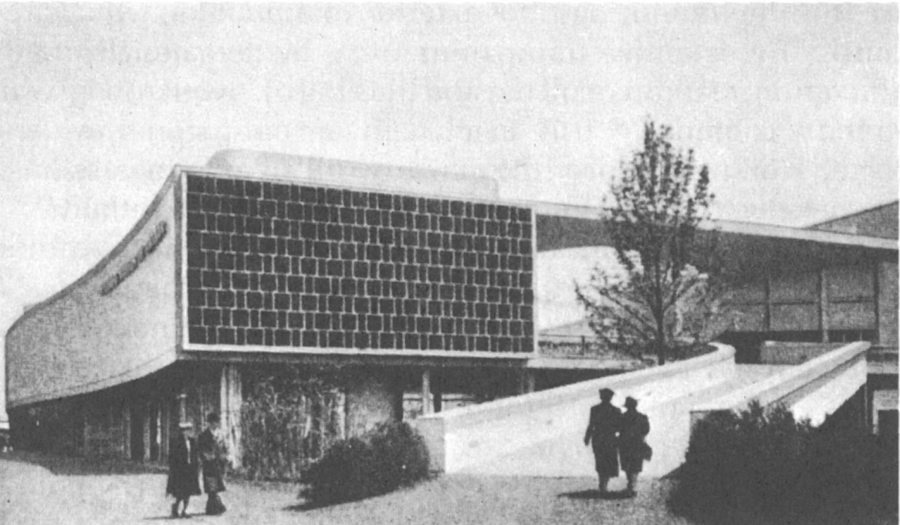

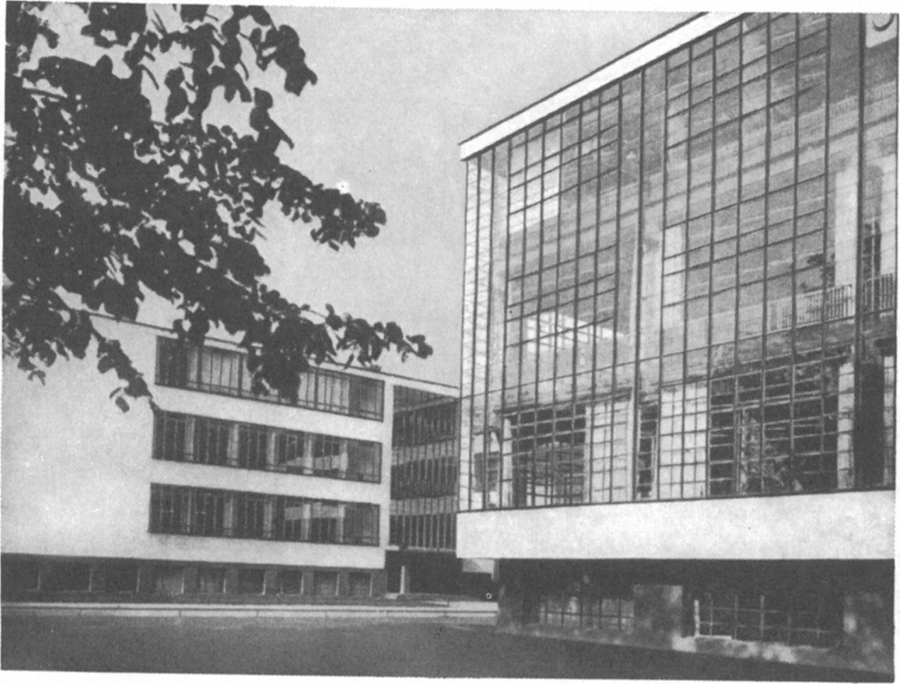

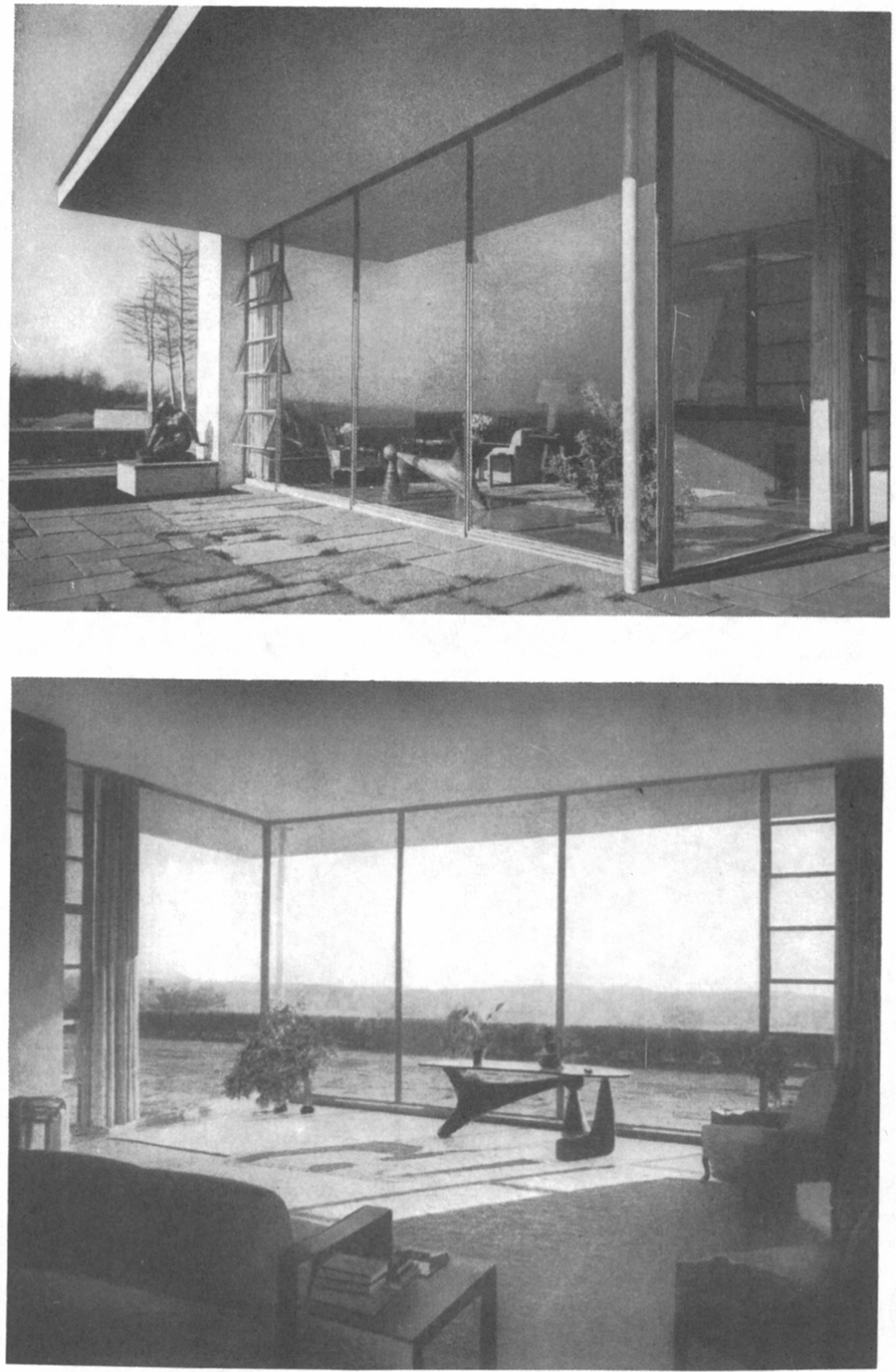

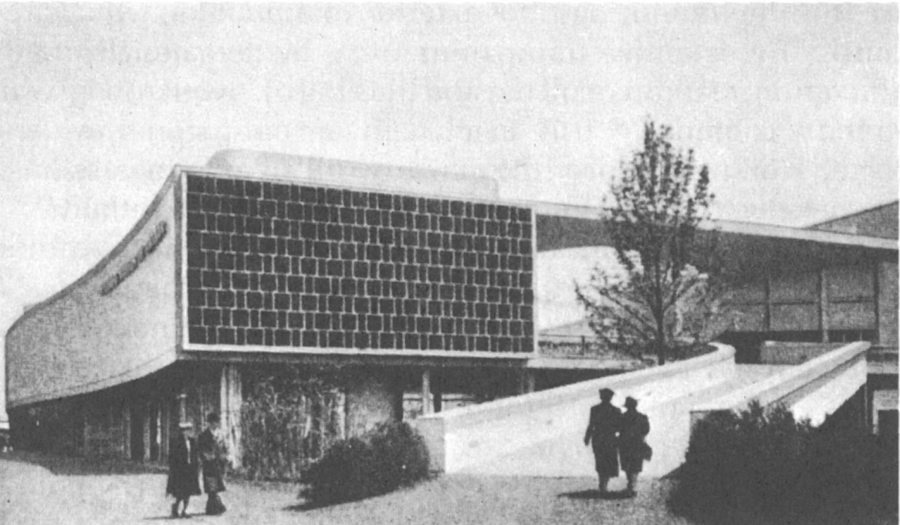

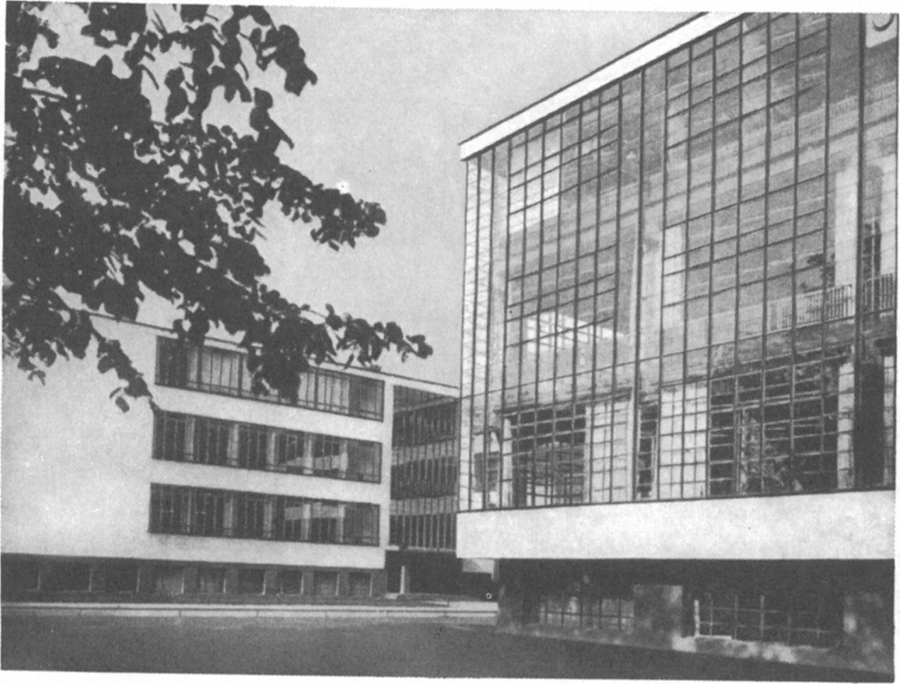

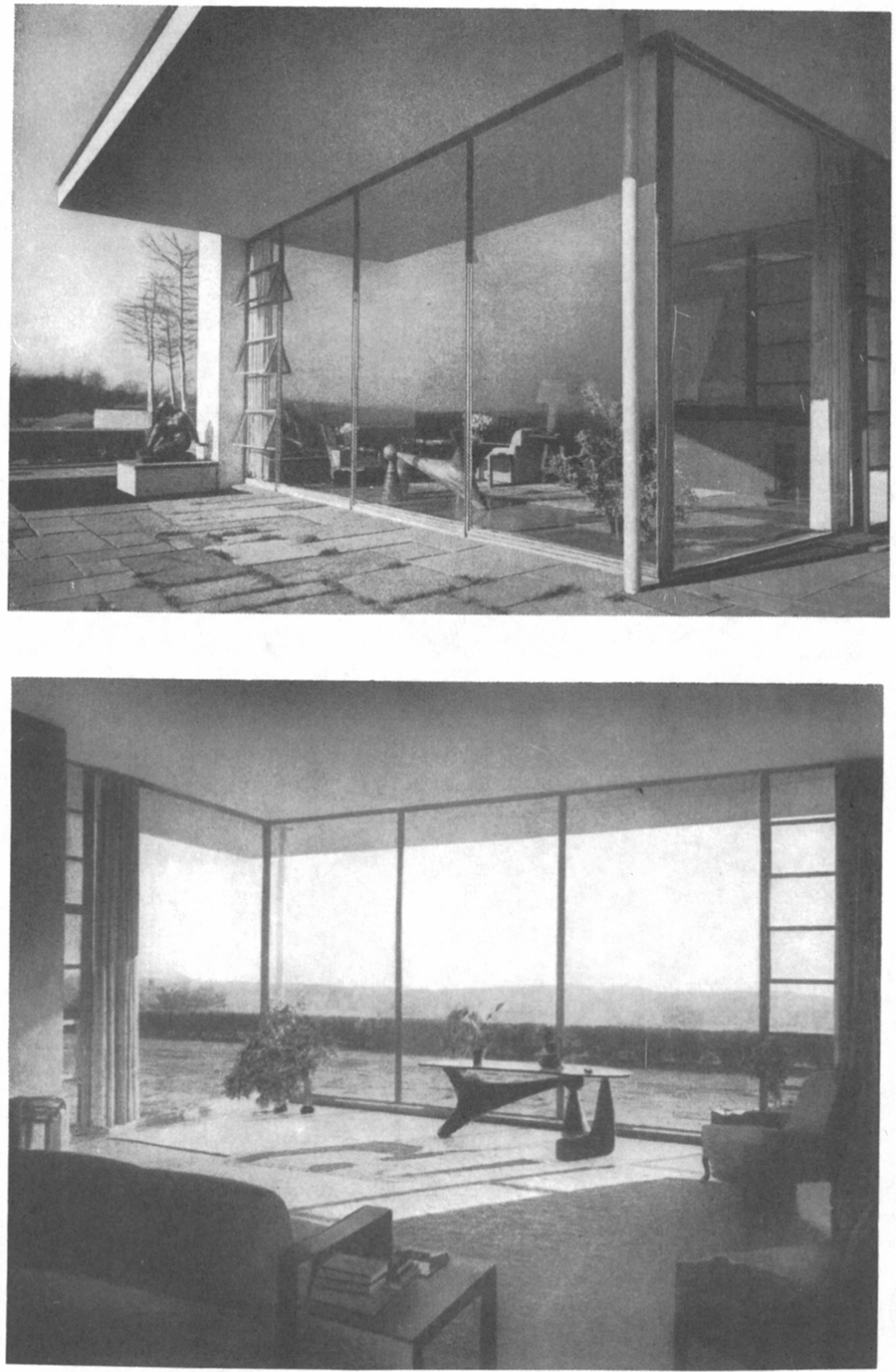

2. Architecture

Architecture: The sociological Art 464—The Solution of the Time Problem by the New Architecture; “Fluid Space;” Wright’s “Organic Architecture” 465—The “Free Plan” and the “Free Curve;” “Open Space” and the Supersession of the Dualism of Inside and Outside 467—The Arationality and Diaphaneity of the New Architecture 468

3. Painting

Precursors of the New Mode of Perception: Füssli, Géricault, Delacroix; Cézanne’s Spherical Representational Space 471—The Fourth Dimension and the Cubists 476—Simultaneity is not Time-Freedom 477—The Supersession of Dualism Initiated by the Use of Complementary Colors 478—Its Continuation by Cézanne; Klee and Gris; The Loss of the Middle not a Loss but a Gain of the Whole 479—The Arationality of the New Painting: Picasso’s Lack of Intent and the “Open Figures” of Lhote 480—The “Hidden Structure” of Things (Picasso); The “World without Opposites” a Gain of Being Together, not a Loss 481—Impressionism, Pointillism, Primitivism, Fauvism, Expressionism, Futurism, Cubism, and Surrealism as Temporic Attempts 481—“In the Origin of Creation” (Klee); The “Roots of the World” (Cézanne) 483—Diaphaneity in the Works of Léger, Matisse, and Picasso 486

4. Literature

Literature as the History of the Date-less 487—An Aphorism of Hölderlin 489—The Theme of Time in Poetry 490—The New Estimation of the Word since Hölderlin and Leopardi 491—And in French, Spanish, English, and German Poetry 491—The Psychic Element from Romanticism to James Joyce; Expressionists, Dadaists, Surrealists, Nihilists, Infantilists, and Pseudo-Myth-Makers as Destroyers of Rigidified Forms 492—Proust’s Struggle for Time-Freedom 494—The Spatio-temporal Mode of Writing in the Work of Joyce and Musil; Virginia Woolf, Thomas Mann, and Herman Hesse and the Time-Problem 495—The Recent Americans and Hermann Broch; Musil’s Maxim and the Post-War Generation 496—Hopkins and Eliot 497—Inversions and Stylistic Fractures as an Expression of the Revaluation of Time (Rilke and Mallarmé) 497—The Aperspectival Use of the Adjective 498—The Rejection of “Because” and Simile: a Rejection of Perspectival Fixity 499—The New Use of the Comparative as an Aperspectival Relation; the New Beginnings with “And” 499—The New, Aperspectival Rhyme in European Poetry 501—The Supersession of Dualism and the New Attitude toward Death 502—The Arationality of the New Poetry; the Diaphaneity of Guillén, Eliot, and Valéry 503—Aperspectival Poetry and Aperspectival Physics 504

Chapter Ten: Manifestations of the Aperspectival World (VI): Summary

1. The Aperspectival Theme

The Necessity of a New Awakening of Consciousness 528—The Aperspectival Themata; Praeligio 529—Aperspectival Reality 529

2. Daily Life

The Completion of the Mutation in the Public Consciousness 530—Factory and Office as our Self-imposed Falsifications of Time; Free Time and Time-Freedom 531—Necessary Achievements for the Individual 532

Chapter Eleven: The Two-Fold Task

Spengler’s Self-Relinquishment and Our Task 535—The Perils in the Various Areas of our Thinking and Action during our Transitional Age 536

Chapter Twelve: The Concretion of the Spiritual

Mental Thought and Spiritual Verition (“Awaring”); The Spiritual is not Spirit but Diaphaneity (Transparency); Concrescere, the Coalescence of the Spiritual with our Consciousness as the Concretion of the Spiritual 542—Integrity or the Whole 543

Postscript

Remarks on Etymology

Prefatory Note

1. The Root “kē̆l”

2. The Root Group “qer:ger (gher):ker”

3. The Root Group “kel:gel:qel”

4. The Mirror Roots “regh” and “leg”

5. The Root “da:di”

Index of Names

Index of Subjects

Synoptic Table

Translator’s Preface

As early as 1951, even before publication of the second part of Jean Gebser’s Ursprung und Gegenwart, the Bollingen Foundation contemplated the feasibility of an English-language version and requested an estimation of the book by Erich Kahler (Princeton), the distinguished philosopher of history and author of studies of the evolution of human history and consciousness (Man the Measure, 1943; The Tower and the Abyss, 1957). In his eight-page review Professor Kahler encouraged publication, calling the book “a very important, indeed in some respects pioneering piece of work,” “vastly, solidly, and subtly documented by a wealth of anthropological, mythological, linguistic, artistic, philosophical, and scientific material which is shown in its multifold and striking interrelationship.” He also noted that Gebser’s study “treads new paths, opens new vistas” and is “brilliantly written, (introducing) many valuable new terms and distinctions (and showing) that scholarly precision and faithfulness to given data are compatible with a broad, imaginative, and spiritual outlook.”

Despite this warmly appreciative and incisive estimation, the Bollingen Foundation apparently did not pursue the project further, for Gebser’s correspondence with his German publisher mentions a New York option under another name (letter of May 21, 1953) which also was not acted upon. The following year a part of Chapter three was printed in the periodical Tomorrow: Quarterly Review of Psychical Research (Summer, 1954 issue, vol. 2, no. 4, pages 44–58) in the author’s own English rendering (reprinted here in its entirety pp. 46–60 and p. 106 note 43 below), and later negotiations were taken up by the author with the London firm of George Allen & Unwin, but owing to the death of one of the partners, no agreement was signed.

Because of the continuing interest in Gebser’s work by readers and contributors of the journal Main Currents in Modern Thought, its editor, Mrs. Emily Sellon, sought to obtain foundation support for a complete translation (also from the Bollingen Foundation), and solicited from the author in 1971 a chapter to be included in the periodical. Unfortunately Jean Gebser’s declining health made it impossible for him to prepare a translation himself and the extracts printed in the November-December issue of 1972 (Main Currents, vol. 29, no. 2, pp. 80–88) were translated by Kurt F. Leidecker. Dr. Leidecker subsequently asked Algis Mickunas to collaborate on a translation of the entire work, a project which did not materialize. Jean Gebser died on May 14, 1973.

In 1975 Professor Mickunas invited the undersigned to collaborate on a translation and arranged a contract with the Ohio University Press. A preliminary version of the entire text was prepared jointly during the next three years. After discussions with the author’s widow, Dr. Jo Gebser, in April of 1977 the undersigned undertook a complete retranslation and revision of the text and is responsible for the English version in its present form.

The translation is based on the text of the 1973 edition of the German original which the author had revised for publication shortly before his death. Several corrections from Gebser’s own papers were supplied following the death of Dr. Jo Gebser in June of 1977 by Dr. Rudolf Hämmerli, Jean Gebser’s literary executor and co-editor of the collected edition of Gebser’s works (Jean Gebser Gesamtausgabe, Schaffhausen: Novalis Verlag, 1975–1981, eight volumes and index). References in the present work to the author’s other publications now collected in this edition were prepared for both publications jointly by Dr. Hämmerli and the undersigned.

For the English translation a new index was compiled primarily on the basis of the author’s own indexes to the first edition (1949/1953) and the translator’s notes (later editions of the original contained abridged indexes by others). The extensive cross-referencing in the index of subjects is intended, as in the original, to draw attention to terms and ideas which are used in the text more or less interchangeably.

The wording of the English title is that of the author himself (letter of August 20, 1971 to Emily Sellon). Included on pp. 277–278 below is the text of an introduction to the second part written by Jean Gebser in 1953 for the house publication Die Ausfahrt of the Deutsche Verlags-Anstalt, publisher of the original. A remark on editorial changes in the annotations can be found on p. xxxii.

In conclusion I would like to express appreciation to the many persons who have contributed to the realization of an English version, particularly to Mrs. Emily Sellon and the staff and contributors of Main Currents; to the late Dr. Jo Gebser (Bern), the author’s widow, who supported the project from its inception and decisively aided its completion; to Mr. Georg Feuerstein (Durham, England), who at the request of the author’s widow read and annotated several chapters of the preliminary manuscript and gave much-needed encouragement during later stages of publication; to Dr. Rudolf and Mrs. Christiane Hämmerli (Bern) for providing books and information as well as access to Jean Gebser’s archive and library in addition to the contributions noted earlier; to Mrs. Märit Schütt and Ms. Petra Bachstein of the Deutsche Verlags-Anstalt (Stuttgart) for contractual arrangements and extensions, as well as for making available letters of the author and other archival materials relating to the original publication; to Professor Jean Keckeis (Neuchâtel) for permission to include my translation of his “In memoriam Jean Gebser“ as the introduction to this edition; to Mrs. Alice L. Kahler (Princeton) for placing at my disposal Erich Kahler’s review and for providing other materials and information including a copy of a letter by Jean Gebser to Austrian novelist Hermann Broch from the correspondence mentioned in the text (p. 496 below); and to the staff of the Ohio University Press for their interest and co-operation at all stages of preparing and publishing the manuscript.

The text of this fifth printing of the paperback edition, as in the 1986, 1989, 1991, and 1994 editions, has been emended to achieve a more accurate and felicitous wording of several passages and to eliminate some of the remaining typographical errors. I remain indebted to Elizabeth Behnke (Felton, CA), Georg Feuerstein (Lower Lake, CA), and Helen Gawthrop (Ohio University Press) in particular for their many invaluable suggestions toward improving the text.

March 1997

Noel Barstad

In memoriam Jean Gebser

by Jean Keckeis

While completing his studies in Berlin during his mid-twenties—a time of precarious circumstances, as the inflation had abolished the family reserves—Jean Gebser wrote a poem entitled “Many Things are About to be Born,” which begins: “We always lose our way / when overtaken by thinking . . . ,” a thought which surely reflects a premonition of his later intellectual and spiritual journey.

Born in Posen in 1905, Gebser received his schooling in Königsberg and later in the renowned preparatory school in Rossleben on the Unstrut. He has left us a fine account of how he learned there to “swim free”; ever since a jump from the diving board “into uncertainty,” he was in possession of something that he did not fully realize until decades after. “It was then,” he wrote later, “that I lost my fear in the face of uncertainty. A sense of confidence began to mature within me which later determined my entire bearing and attitude toward life, a confidence in the sources of our strength of being, a confidence in their immediate accessibility. This is an inner security that is fully effective only when we are able to do whatever we do not for our own sake. . . .”

Following his first-hand experience of the Brown Shirts in Munich in 1931, Gebser left Germany of his own free will and went, penniless, to Spain. There the difficult decision to forego his mother tongue was rewarded by the “enriching knowledge of the Latin way of thinking, acting, and living.” He became sufficiently familiar with Spanish culture to hold for a time a position in the Republican Ministry of Culture and even to write poetry in the language of his friend Federico García Lorca (Poesias de la Tarde, 1936). Twelve hours before his Madrid apartment was bombed in the Autumn of 1936 he again set out on the path of uncertainty.

By this time he had already formed the conception of his magnum opus, The Ever-Present Origin, a conception which matured during three years of privation in Paris during his association with the circle around Picasso and Malraux. The necessary repose for completion of the work Gebser found in Switzerland, where he arrived near the end of August, 1939, two hours before the frontier was closed. He became a Swiss citizen in 1951. Unfortunately, Gebser was unable to assume the duties associated with his chair for the Study of Comparative Civilizations at the University of Salzburg; a progressively worsening case of asthma forced him to remain ever closer to his home in Berne and to avoid exertion. The flights of spirit of which he was then still capable are perhaps better known outside Switzerland; and unlike the Swiss, with their predilection for specialized knowledge as such, Gebser went on to transform a prodigious and multifaceted knowledge, gleaned with rare sensitivity from ancient to avant-garde sources, into Bildung, wisdom and sophrosyne. A glance at the Festschrift to commemorate his sixtieth birthday, Transparent World (Transparente Welt, Berne: Huber, 1965) provides evidence of the universal emanation of his creativity, which is further attested to by his extensive list of publications.

Jean Gebser did not live to see the completion of a project close to his heart (he died on May 4, 1973 in Berne): the publication of his Ever-Present Origin in an inexpensive paperbound edition (Munich: Deutscher Taschenbuchverlag, 1973, three volumes). This edition was to make the work more accessible to students and other young people who have shown their concern with a new consciousness and a new orientation toward the world.

The path which led Gebser to his new and universal perception of the world is, briefly, as follows. In the wake of materialism and social change, man had been described in the early years of our century as the “dead end” of nature. Freud had redefined culture as illness—a result of drive sublimation; Klages had called the spirit (and he was surely speaking of the hypertrophied intellect) the “adversary of the soul,” propounding a return to a life like that of the Pelasgi, the aboriginal inhabitants of Greece; and Spengler had declared the “Demise of the West” during the years following World War I. The consequences of such pessimism continued to proliferate long after its foundations had been superseded.

It was with these foundations—the natural sciences—that Gebser began. As early as Planck it was known that matter was not at all what materialists had believed it to be, and since 1943 Gebser has repeatedly emphasized that the so-called crisis of Western culture was in fact an essential restructuration. (It was in 1943 that his Transformation of the Occident was first published [Zürich/New York: Oprecht; also Dutch, French, Italian, and Swedish editions], an estimation of the results of research in the natural sciences during the first half of the century.) Gebser has noted two results that are of particular significance: first, the abandonment of materialistic determinism, of a one-sided mechanistic-causal mode of thought; and second, a manifest “urgency of attempts to discover a universal way of observing things, and to overcome the inner division of contemporary man who, as a result of his one-sided, rational orientation, thinks only in dualisms.” Against this background of recent discoveries and conclusions in the natural sciences Gebser discerned the outlines of a potential human universality. He also sensed the necessity to go beyond the confines of this first treatise so as to include the humanities (such as political economics and sociology) as well as the arts in a discussion along similar lines. This was the point of departure for The Ever-Present Origin.

Here a word might be in order about Gebser’s “method.” No later than during his sojourn in Spain he must have acquired the “Mediterranean way of thought” (as Ortega y Gasset might have called it) for which existence—the external, the concrete—is more important than the inward, the abstract, the mere awareness of being. What Gebser presents in The Ever-Present Origin was incubated, not in the study, but in the warmth of living contact with representatives of all disciplines. His examination of the present restructuration of reality and of the establishment of a new consciousness structure led him to discover earlier restructurations in mankind’s consciousness development. Accordingly, the first part of the book (first published in 1949), based on research and insights of ethnology, psychology, and philology, uncovers the “Foundations of the Aperspectival World” in which we now find ourselves (although there is an unwillingness in certain quarters to accept this as a fact). We have evidence that human consciousness has undergone three previous mutations: from the archaic or primordial basic structure the magic, the mythical, and the mental (or rational) structures have emerged. The term “consciousness structures” is to be understood as nothing other than the visibly emerging perception of reality throughout the various ages and civilizations.

This does not imply, however, that the later consciousness structures obliterate the earlier—we retain in ourselves irrevocable magic and mythical elements, origin and the present—; nor is it to suggest that a given later consciousness structure is of greater “value” than the earlier, although man has demonstrated at all times the understandable weakness of overestimating and exclusively utilizing the most recent potentialities that manifest themselves in him. This is perhaps most clearly exemplified by the hubris still evident in many quarters that overemphasizes the ratio and attempts to subordinate all else to man’s calculating reason and will.

During the interim between the publication of the first and second parts of The Ever-Present Origin—the second is an exploration of the “Manifestations of the Aperspectival World”—an important symposium was held at which prominent representatives of the various arts and sciences themselves presented the evidence of the contemporary restructuration which Gebser has demonstrated. Eighteen specialists presented two cycles of lectures at the Academy of Commerce in St. Gallen, Switzerland (1950-51), on the subject of the “New Perception of the World” which were later published in the two volumes of Die neue Weltschau (Stuttgart: Deutsche Verlags-Anstalt, 1952-53). A surprising unanimity of basic conception emerged from these lectures: an openness toward questions dealing with transcendence; a scepticism about a self-satisfied rationalism; and a courageous humility vis-à-vis insights into man’s limitations of knowledge and perception—all of these being duly noted in the press accounts. It is such interpretation and sustenance of the life-affirming energies of our epoch that form the substance of the second part of The Ever-Present Origin.

The birth-pangs of the aperspectival, integral perception of the world began in the first decade of our century. The major and unique theme of our juncture, according to Gebser, is the irruption of time into our consciousness. It is a matter of our recognizing time as a quality and an intensity rather than as an analytical system of measurable relationships, its perverted and materialized form in the perspectival age. In the new modality of perceiving the world, time appears to be its fundamental constituent; time, being immeasurable and not amenable to rational thought, emerges ever more clearly as a liberation from previous time-forms. It becomes time-freedom. “Just as the conquest of space was accompanied by a disclosure or “opening up’ as it were of surface, of the unperspectival world, so too is today’s emergent perception of time accompanied by an opening of space.” Today, as the arational-integral begins to supplant the mental-rational, the exhaustion of values at the completion of each consciousness structure becomes evident in the exhaustion and quantification of thought, of our mental capacity, as exemplified by the robot-like thinking of our machines. Nevertheless, the “aperspectival” does not imply the exclusion of the perspectival, rather that its claim of exclusivity must be abandoned in favor of something more encompassing. Gebser has evinced the salient aspects of this new consciousness structure from numerous phenomena in the humanities, the natural and social sciences, and the arts.

In one of his most recent books, The Invisible Origin (Der unsichtbare Ursprung, Olten: Walter, 1970), Gebser has again made evident something hardly describable: “evolution as the realization of a pre-established pattern.” Time and again, physicists, philosophers, psychologists, futurologists, artists, and poets have tried to express in words their intuitions of this ever-present origin. In the spring of 1960, the New Helvetic Society (Berne), with the cooperation of Studio Berne, presented a series of broadcasts with the general title: “Paths to a New Reality“(later published as Wege zur neuen Wirklichkeit, Berne: Hallwag, 1960). Besides Gebser, the participants included the physicist Houtermans, the biologist Portmann, the historian Herbert Lüthy, and historian of law Hans Marti. Toward the close of the series, Gebser came to speak specifically about ideologies as typical outgrowths of a purpose-oriented, perspectivistic era, and demonstrated how these ideologies linger about in the world as lost causes, outdone only by the search for new or “counter“ideologies. Particularly anachronistic are the effects of Christian sects posturing like ideologies.

The following year Gebser published another group of essays which had evolved from lectures of his own entitled “Standing the Test, or Verifications of the New Consciousness“(In der Bewährung, Berne: Francke, 1962). His next book, “Asia Smiles Differently“(Asien lächelt anders, Frankfurt and Berlin: Ullstein, 1968), based on his extensive travels in India, China, and Japan, shows yet another notable aspect of his integral “world perception.“The book first appeared in paperback in 1962 under the title “Asian Primer“and was intended as a brief vade mecum for Westerners to aid in their understanding of the Asian mentality. (The augmented editon of 1968 followed yet another of Gebser’s visits to India.) Both versions of the book document the considerable differences between Western and Eastern ways of thinking. The Asian, for instance, does not experience opposites as dualities or antinomies, as we do in the West, but as complementarities. And in Asia one can still encounter manifestations of what we in the Western world frequently reject as pre-or irrational malfunctions: the magic experience and mythical feeling of the world.

Gebser’s later work further explored and elaborated significant aspects of The Ever-Present Origin. He defined polarity, for example, as “the living constellation of mutual complementation, correspondences, and interdependence,“which he articulated to counter the deadening effects of dualisms. How many misunderstandings come about because we turn interdependencies into antagonisms! He also addressed the subject of “Primordial Anxiety and Primordial Trust,“the subject of his last lecture in October, 1972 at a physicians’ congress in Bad Boll (Württemberg). It is a reply from the profundity of wisdom to the three questions: Where do I come from? Who am I? and Where am I going? These and other essays are now collected in the eight volume edition of his works currently in publication in Switzerland (Schaffhausen: Novalis, 1975–1981).

From a poetic fragment written just three weeks before his death are the verses:

Entirely clear and serene

is the heaven within

and farther, in many ways,

the ascent to origin.

Were they a poetic anticipation of an experience of which he spoke in his last lecture: “Death, too, is birth”? Around 500 B.C., at the time of mutation from the mythical to the rational consciousness structure, Heraclitus had expressed it in the words: “The path of ascent and descent is one and the same.”

(1973)

List of Illustrations

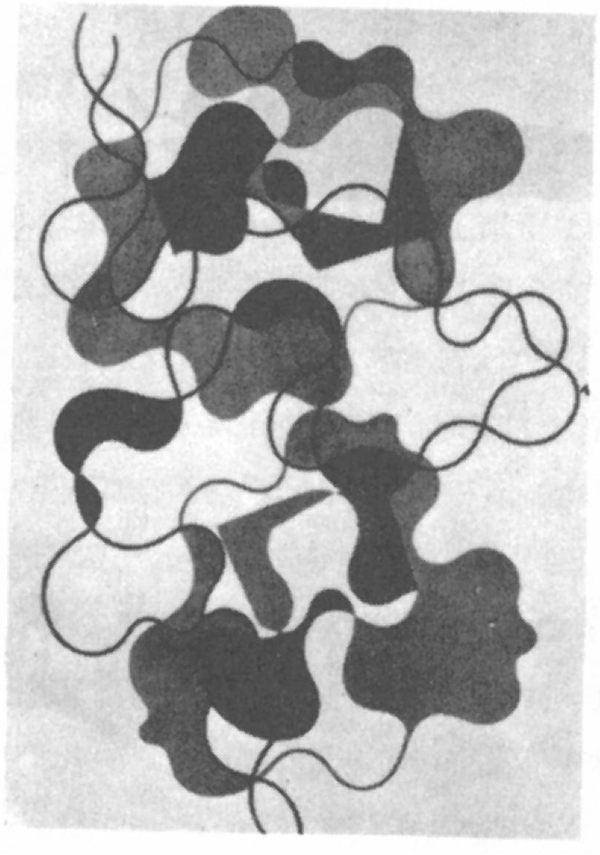

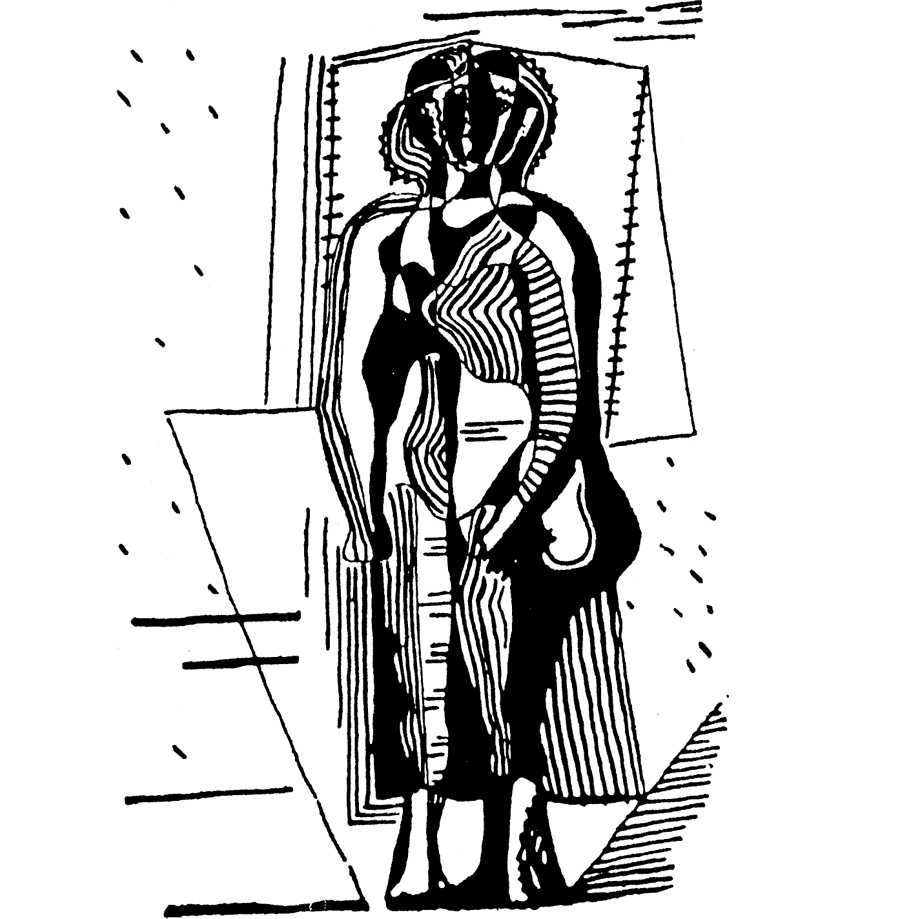

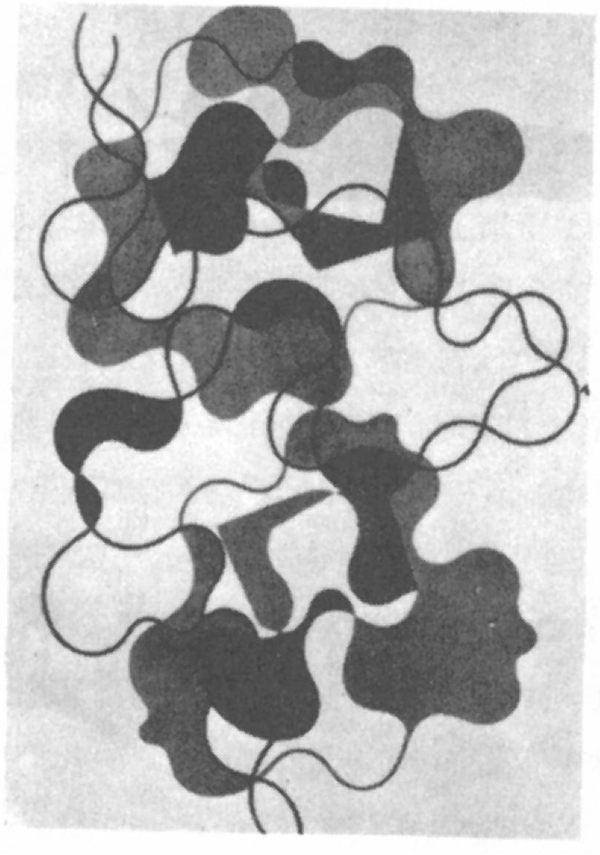

Fig. 1 Pablo Picasso, Drawing (1926)

(By permission of the Galerie Gasser, Zürich)

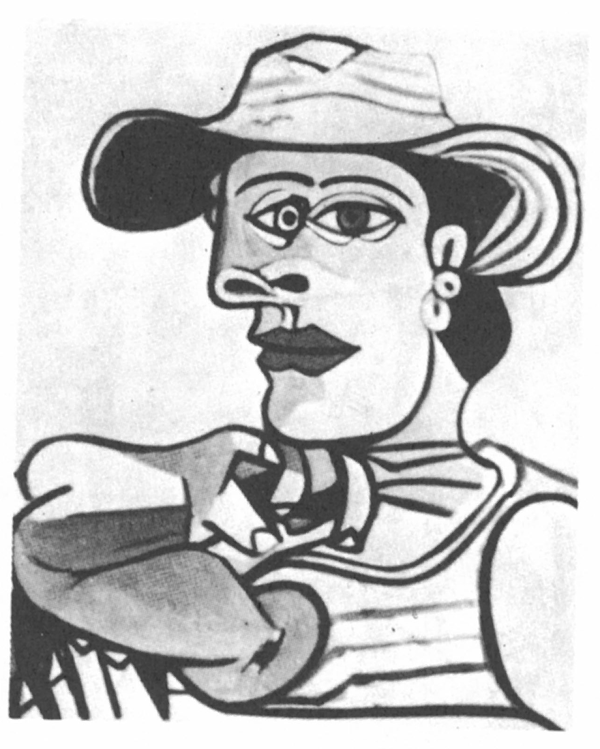

Fig. 2 Pablo Picasso, Le Chapeau de paille (The Straw Hat) (1938)

(From a photograph furnished by the Kunsthalle, Berne)

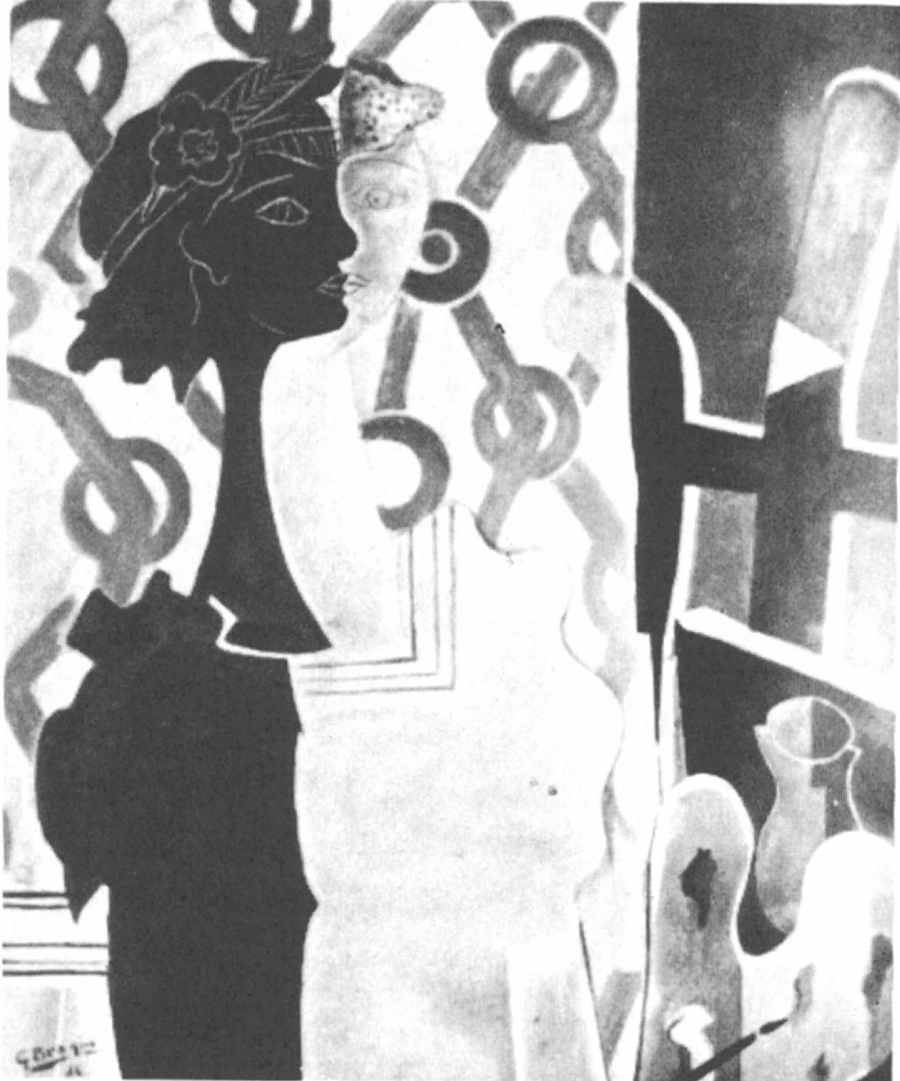

Fig. 3 Georges Braque, Femme au chevalet (Woman before an Easel) (1936)

(By permission of the Galerie Rosenberg, Paris)

Fig. 4 Prehistoric depiction of a bison from the cave at Niaux

(source credit note 38, p. 105)

Fig. 5 “Nubian Battle,” from a painting on a chest from the tomb of Tutankhamen

(source credit note 47, p. 107)

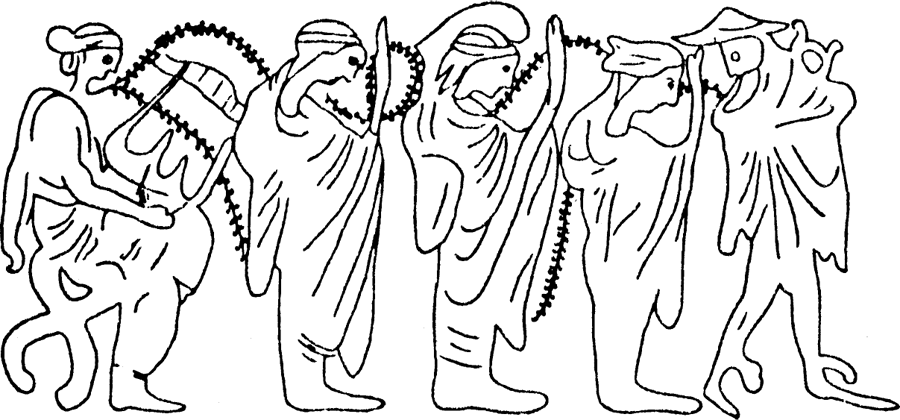

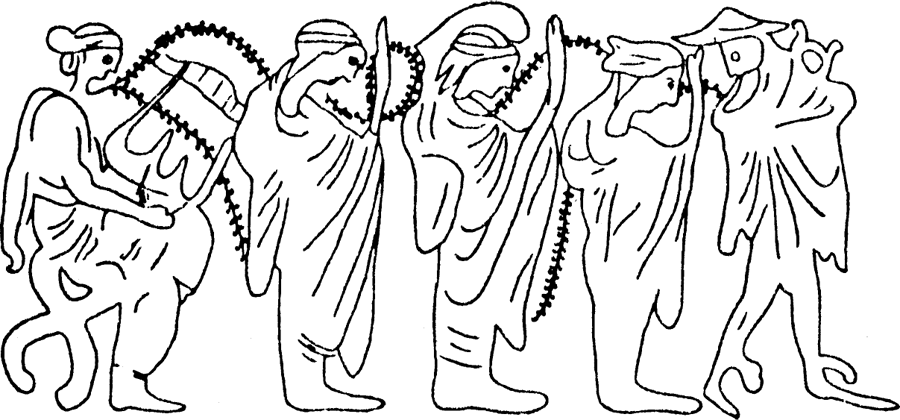

Fig. 6 Fragment of a Boeotian vase drawing

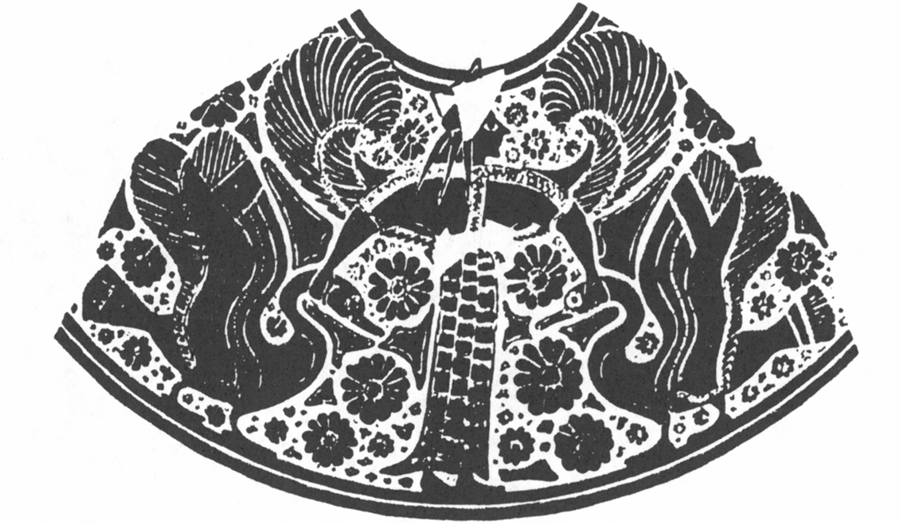

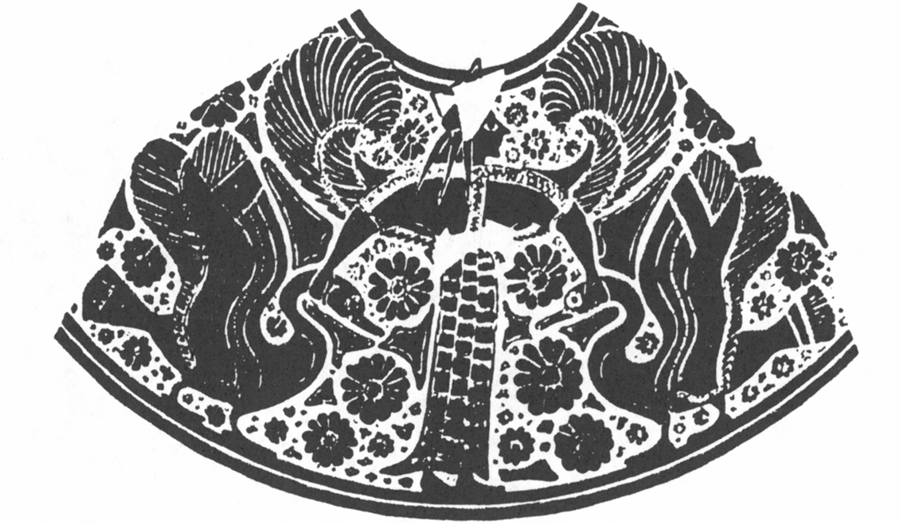

Fig. 7 “Artemis as Mistress of the Animals”; Corinthian vase painting

(source credit note 50, p. 107)

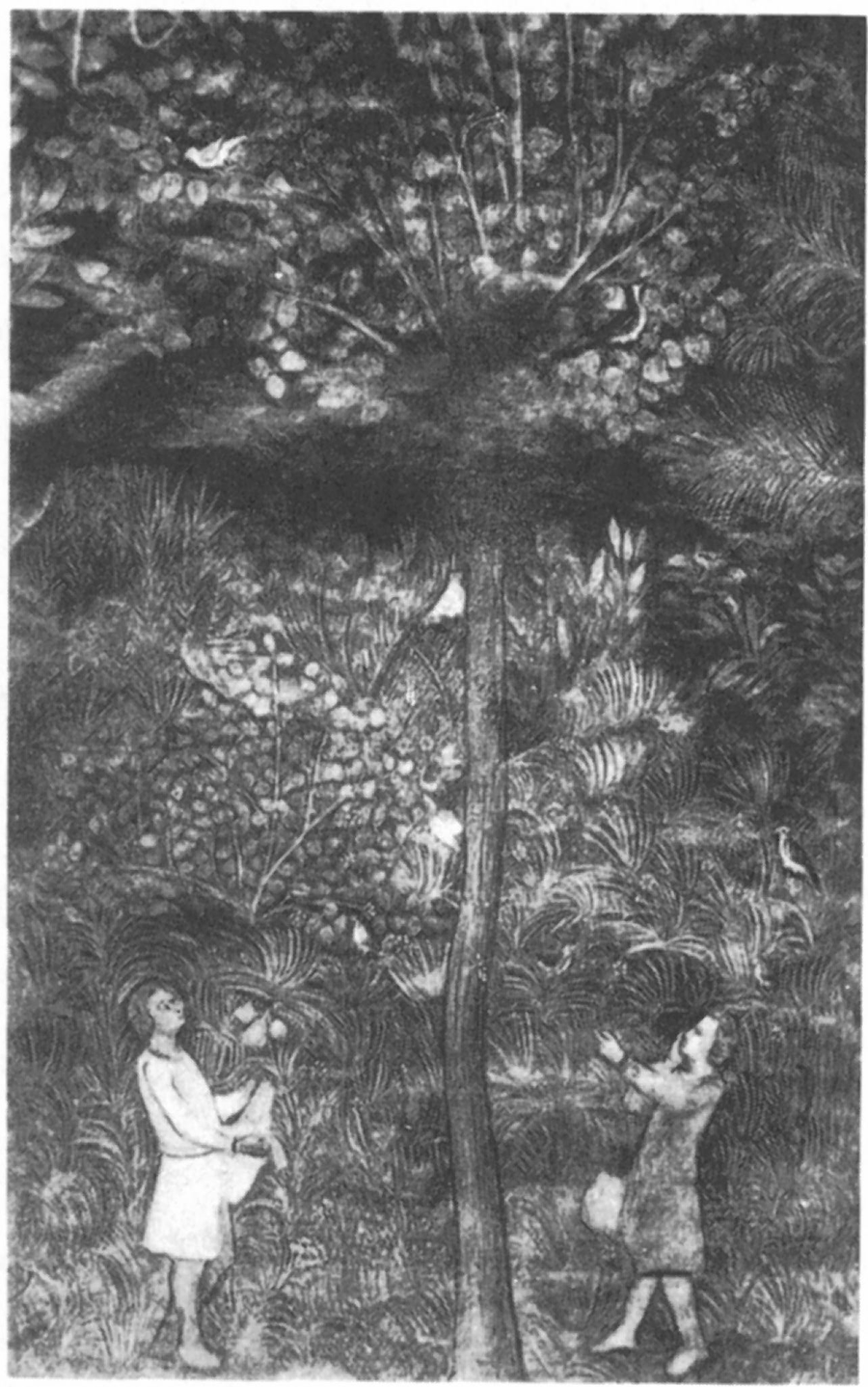

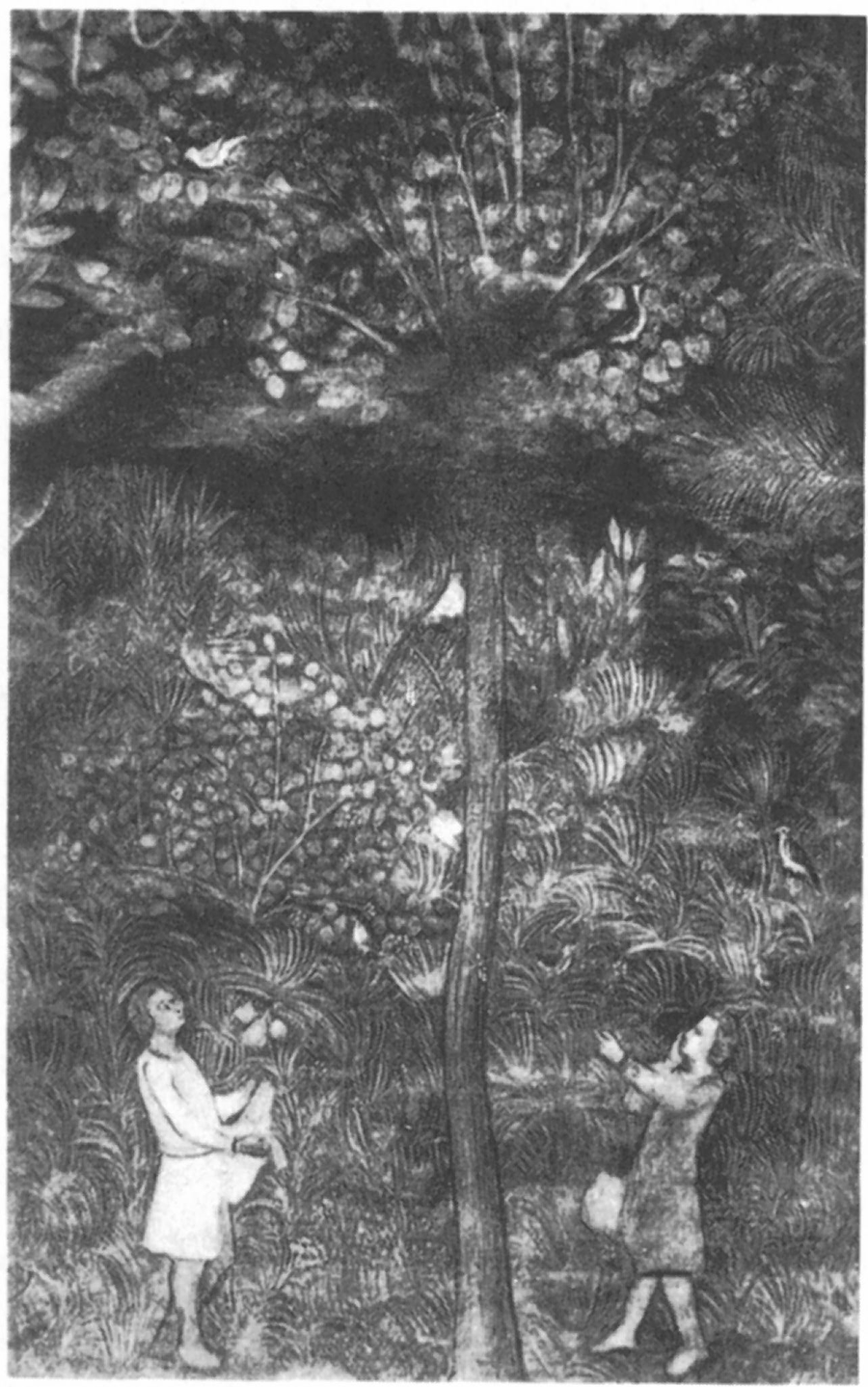

Fig. 8 Fresco in the “Tour de la Garderobe” in the Palace of the Popes, Avignon

Fig. 9 Prehistoric cave drawing from Australia

(source credit note 55, p. 107)

Fig. 10 Irish miniature from a psalter in Dover

(source credit note 57, p. 107)

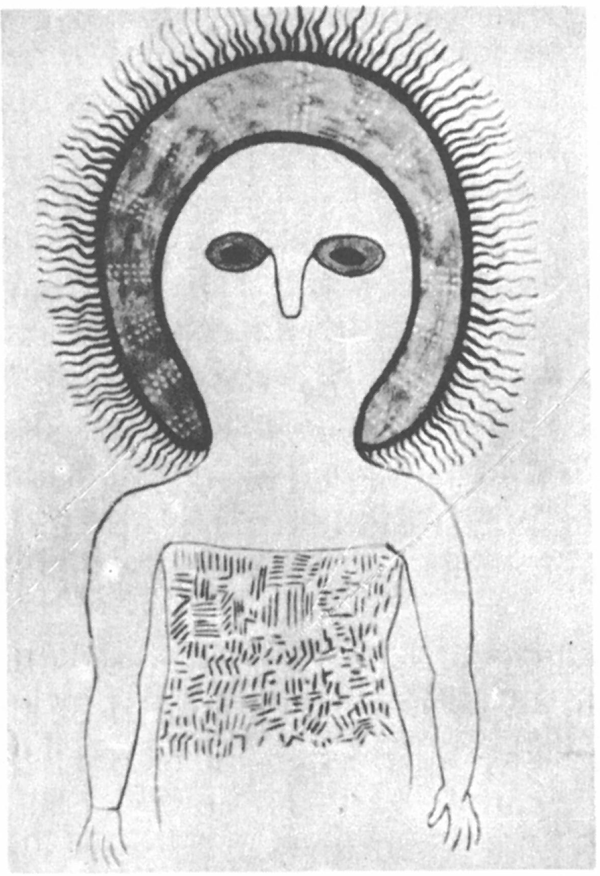

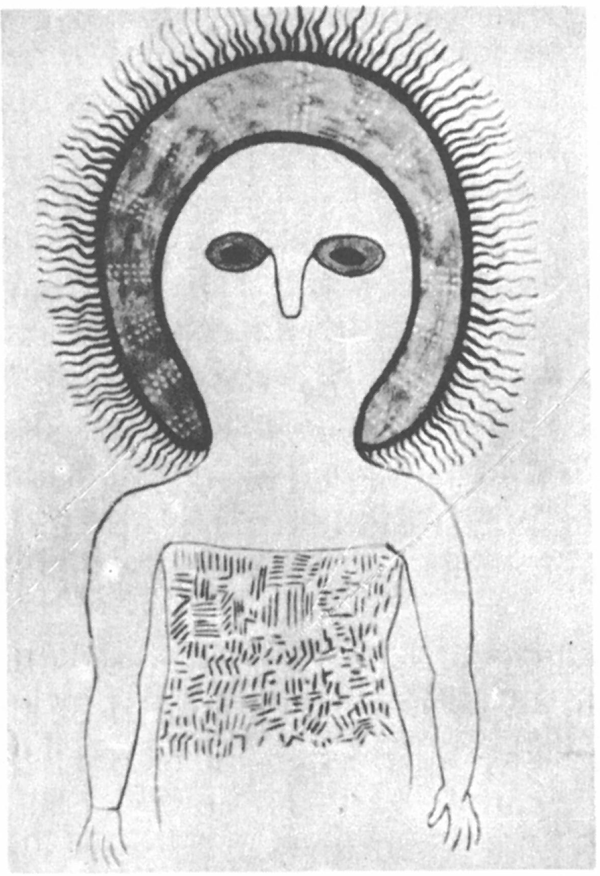

Fig. 11 Prehistoric cave drawing from northwestern Australia

(source credit note 58, p. 107)

Fig. 12 Female idol found at Brassempouy, Dép. Landes (Western France); ivory, reproduced actual size; dates from the middle or upper Aurignacian (Upper Paleolithic period, ca. 40,000 B.C.)

(source credit note 59, p. 107)

Fig. 13 Frontal view of figure 12

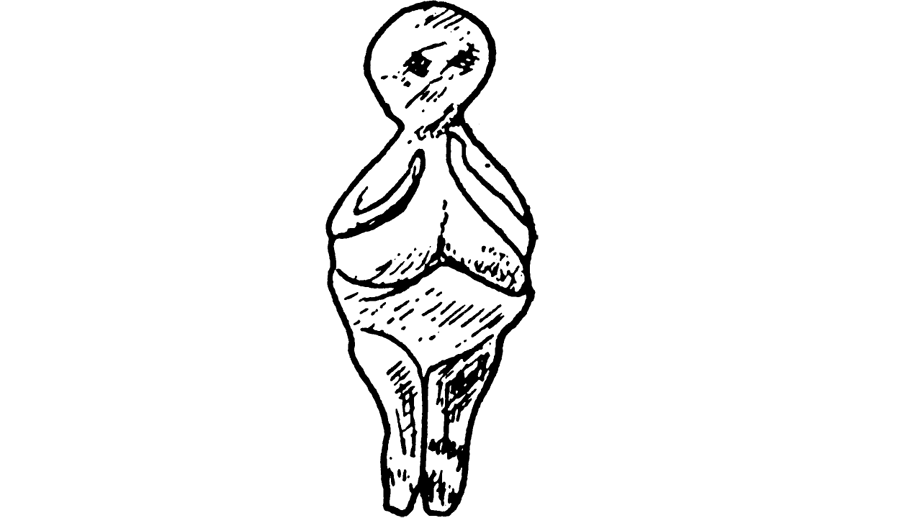

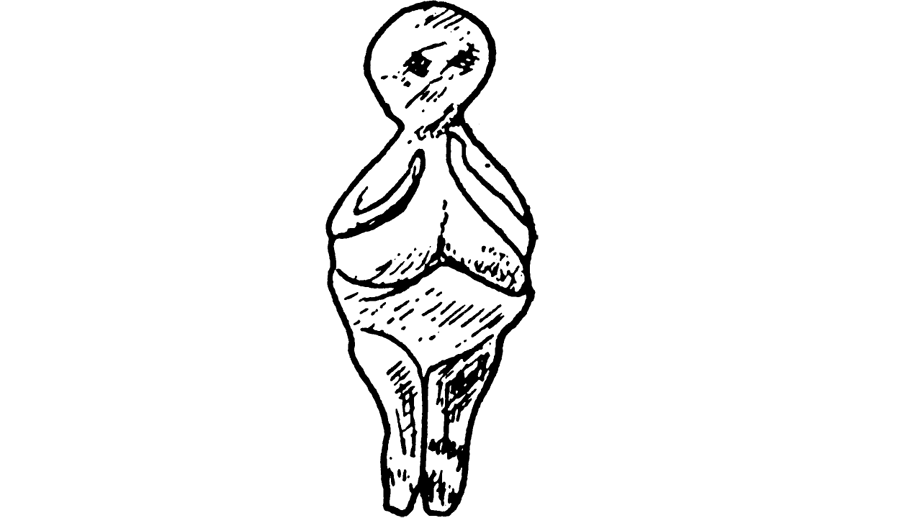

Fig. 14 Female idol found at Gagarino (Upper Don, Tambor province, Lipezk district, Russia); stone, reproduced actual size; dates from the Aurignacian-Perigordian period (Paleolithic, ca. 30,000 B.C.)

(source credit note 60, p. 108)

Fig. 15 Sumerian idol from the Aleppo Museum; fourth to third millenium B.C.

(source credit note 61, p. 108)

Fig. 16 Sumerian idol from the Bagdad Museum; fourth to third millenium B.C.

(source credit as for figure 15)

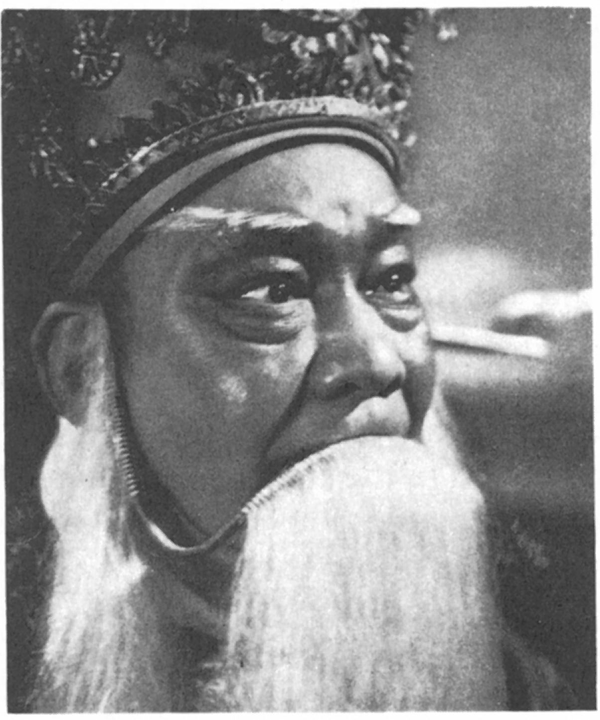

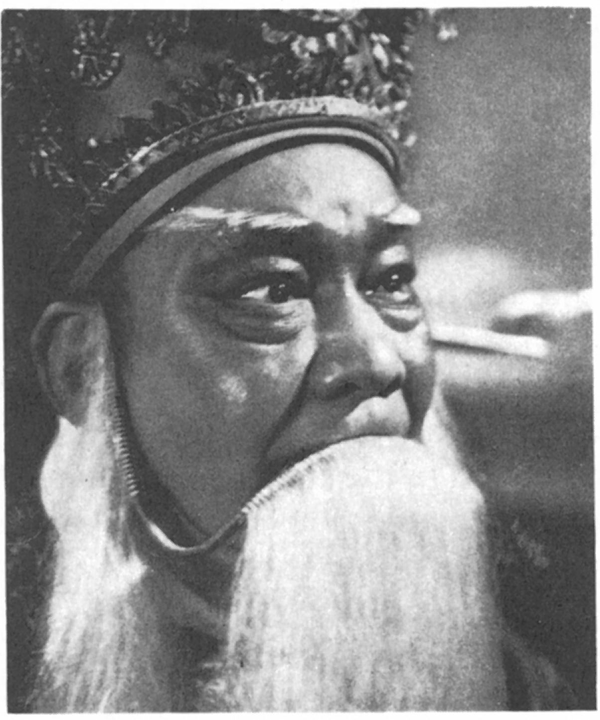

Fig. 17 Chinese mask from the Peking Opera

(source credit note 62, p. 108)

Fig. 18 Bearded mask from the Peking Opera

(source credit note 63, p. 108)

Fig. 19 “The Prince with the Crown of Feathers”; colored stucco relief from Knossos (Crete)

(source credit note 69, p. 109)

Fig. 20 “Hermes accompanied by Hera, Athene, Aphrodite” (and seated muse?); early Greek vase drawing

(source credit note 70, p. 109)

Fig. 21 The muse “Kalliope” from the François vase

(source credit note 76, p. 109)

Fig. 22 Kronos with sickle (from a Hellenistic copper bowl)

(source credit note 13, p. 182)

Fig. 23 Veiled Kronos (after a mural in Pompeii)

(source credit as for figure 22)

Fig. 24 Kronos (on a shield), from an archaic clay pinax found in Eleusis

(source credit note 16, p. 183)

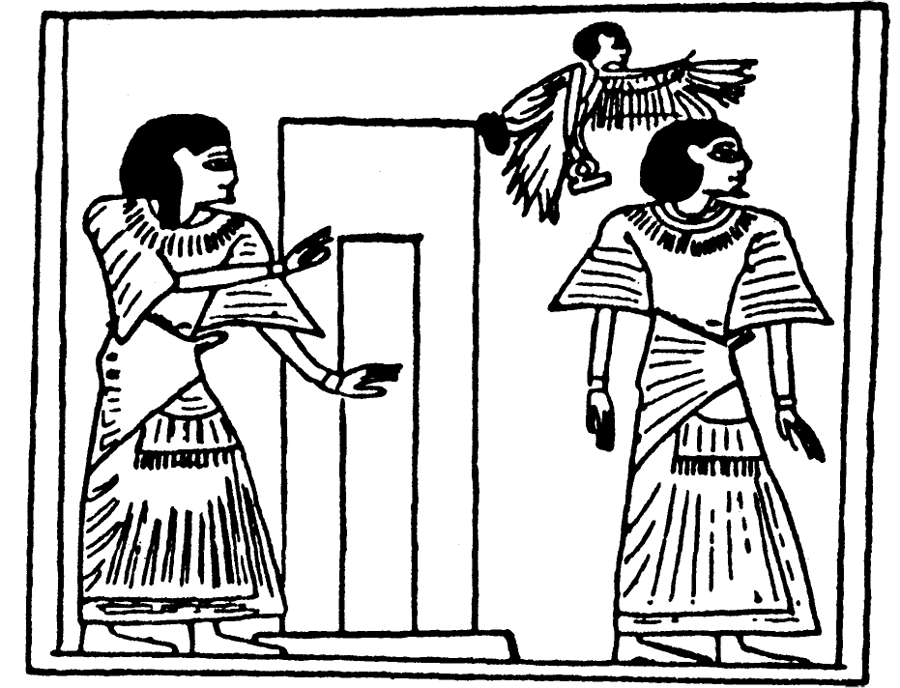

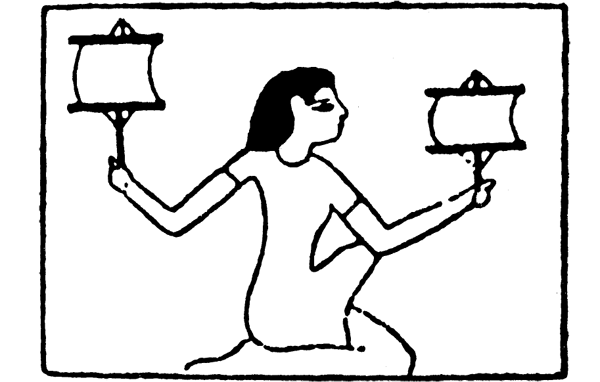

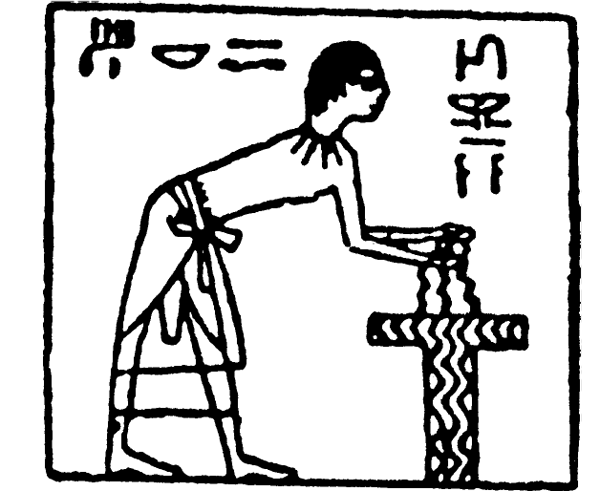

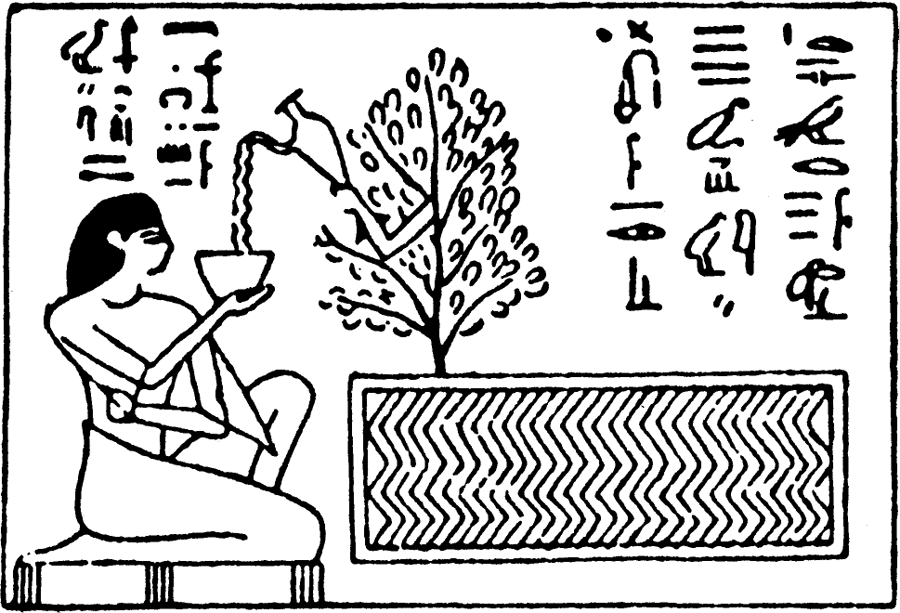

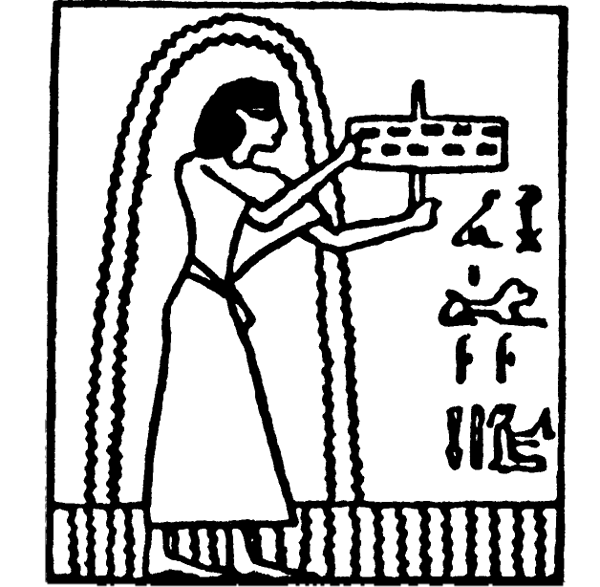

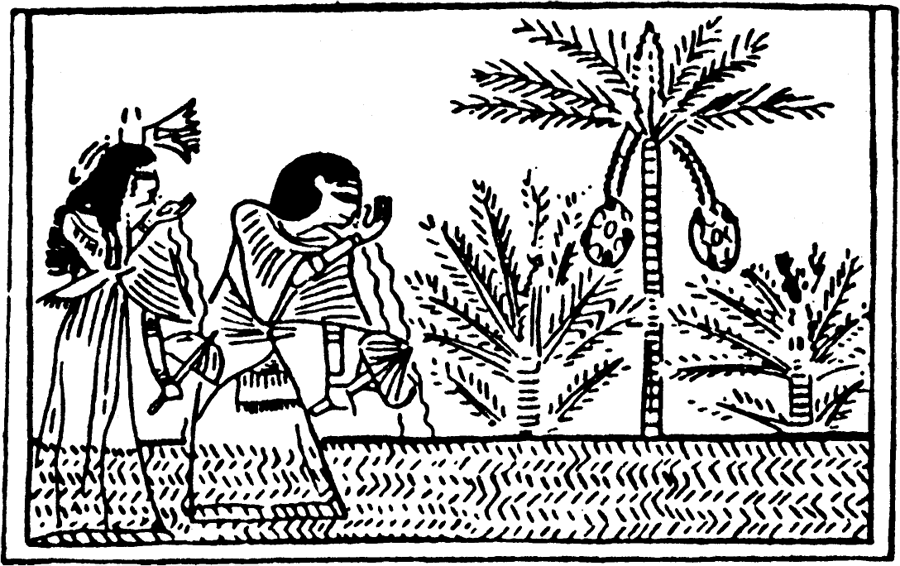

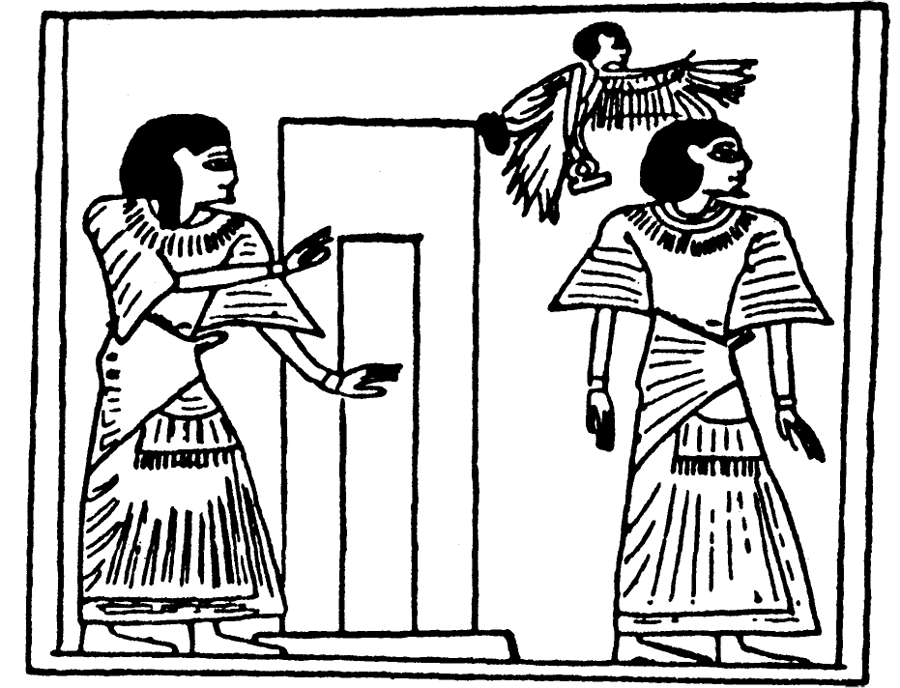

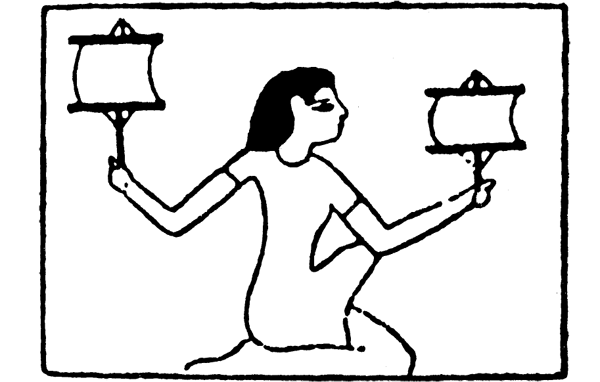

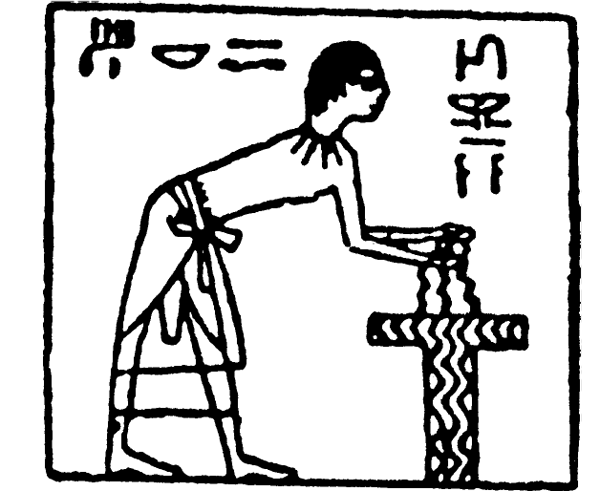

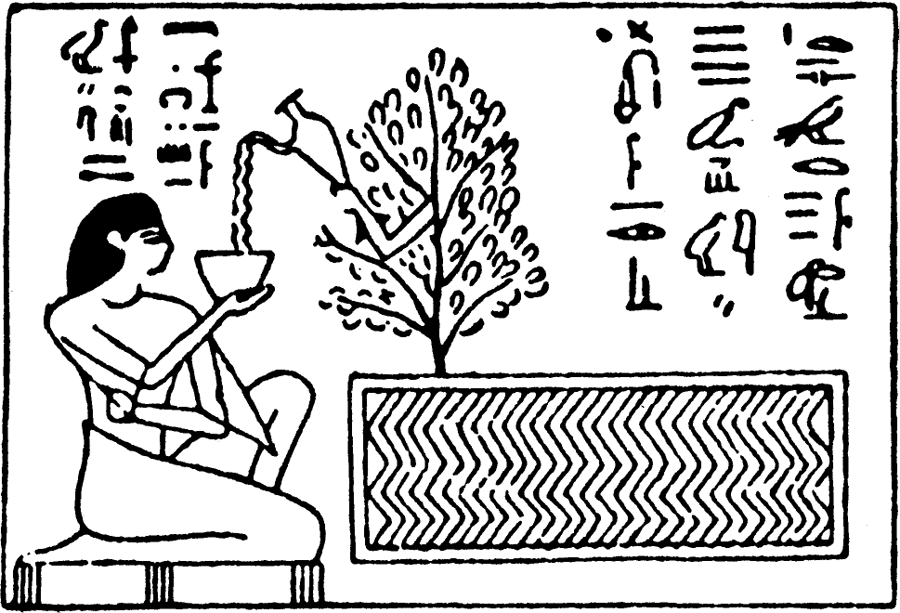

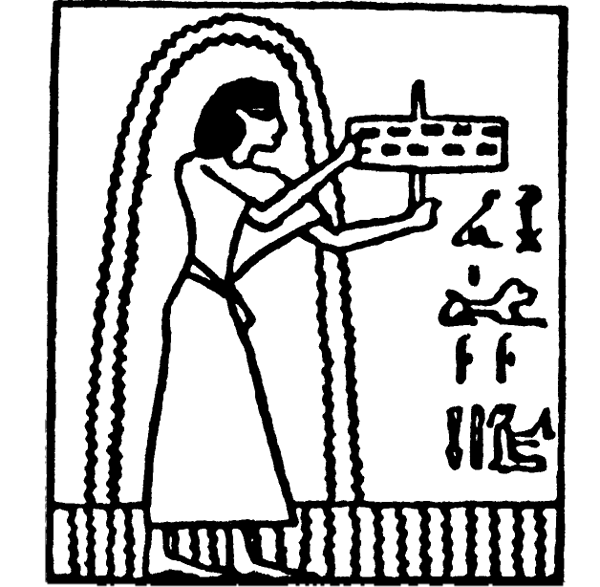

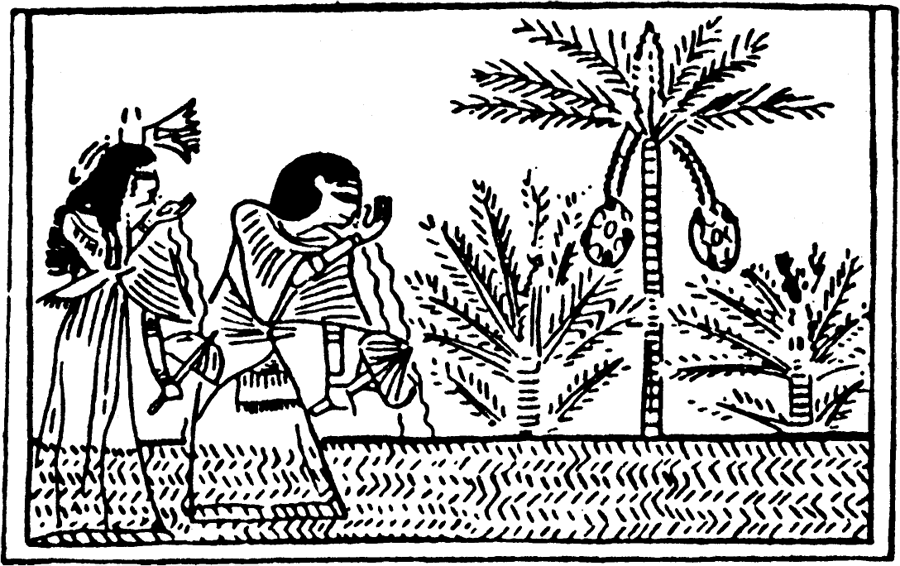

Fig. 25 Vignette from the Book of the Dead (Papyrus of Ani)

(source credit for this and the following vignettes from the Book of the Dead see note 36, p. 239 and the legends accompanying each illustration)

Fig. 26 Vignette from the Book of the Dead (Papyrus of Ani)

Fig. 27 Vignette from the Book of the Dead (Papyrus of Ani)

Fig. 28 Vignette from the Book of the Dead (Papyrus of Ani)

Fig. 29 Vignette from the Book of the Dead (Papyrus of Ani)

Fig. 30 Vignette from the Book of the Dead (Papyrus of Ani)

Fig. 31 Vignette from the Book of the Dead (Papyrus of Nu)

Fig. 32 Vignette from the Book of the Dead (Papyrus of Nu)

Fig. 33 Vignette from the Book of the Dead (Papyrus of Nebseni)

Fig. 34 Vignette from the Book of the Dead (Papyrus of Nu)

Fig. 35 Vignette from the Book of the Dead (Papyrus of Ani)

Fig. 36 The Chinese T’ai-Ki

Fig. 37 Vignette from the Book of the Dead (Papyrus of Nu)

Fig. 38 Vignette from the Book of the Dead (Papyrus of Ani)

Fig. 39 Winged Dolphin (section of figure 41, Plate 8)

(by permission of the British Museum, London)

Fig. 40 Winged Ephebe with Dolphin; bronze, Hellenistic period, from Myrina

(source credit note 87, p. 244)

Fig. 41 Drawing on a Greek bowl

(source credit as for figure 39)

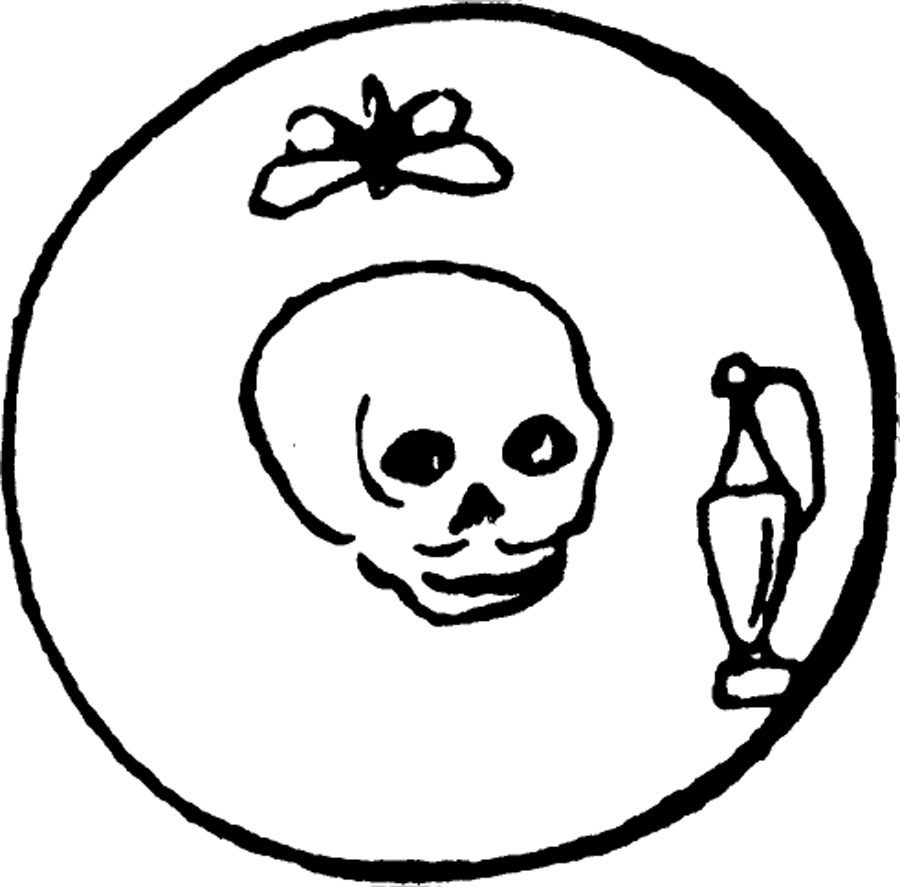

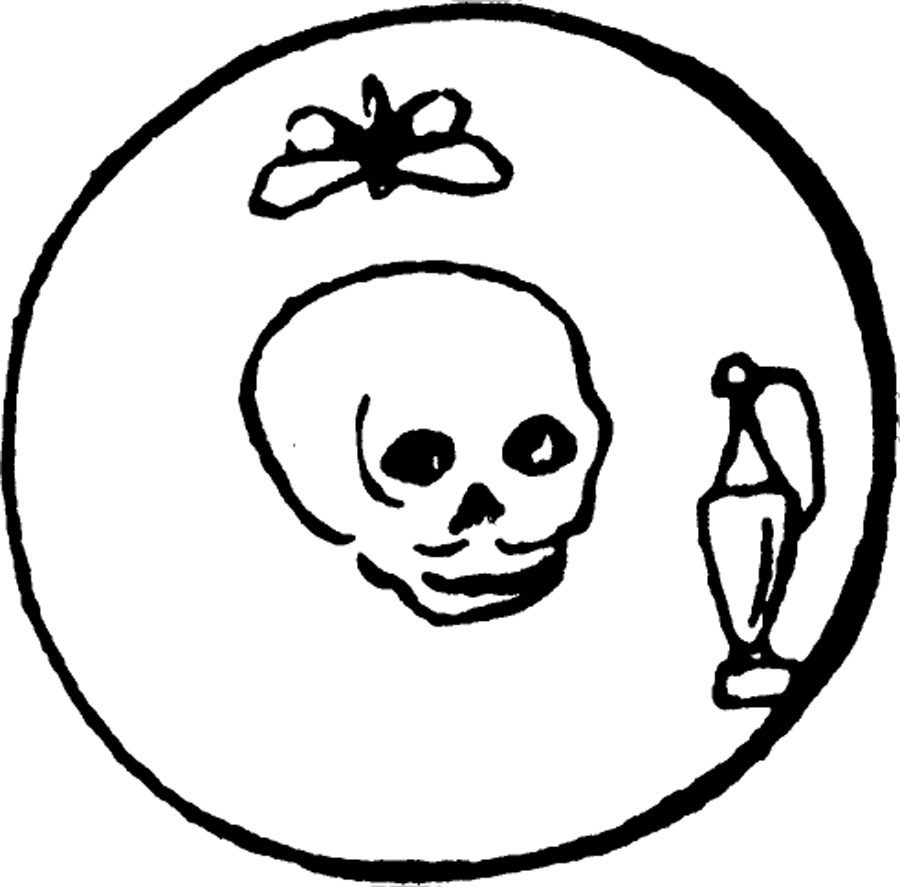

Fig. 42 Glyptograph, early Christian Period

(source credit note 91, p. 244)

Fig. 43 Vignette from the Book of the Dead (Papyrus of Ani)

(source credit note 36, p. 239)

Fig. 44 Kore, Greek, fourth century B.C., from Tanagra

(This and the following Tanagra statuette are from a private collection in Berne, and are here reproduced by permission of the owner.)

Fig. 45 Kore, Greek, third century B.C., from Tanagra

Fig. 46 Mies van der Rohe, German Pavillion at the Barcelona World’s Fair, 1929

(from a photograph reproduced in the book by E. Mock, cited in note 85 on p. 511, p. 10)

Fig. 47 Lucio Costa, Oscar Niemeyer Soares, and Paul Lester Weiner, Brazilian Pavillion at the New York World’s Fair 1939

(source credit as for figure 46, p. 19)

Fig. 48 Walter Gropius, Bauhaus, Dessau, 1925-26

(source credit as for figure 46, p. 11)

Fig. 49 A. and E. Roth, Marcel Breuer, two multi-family dwellings in the Doldertal, Zürich

(with the kind permission of Alfred Roth, from his book; source credit note 95 on p. 512, p. 49)

Fig. 50 Edward D. Stone, A. Conger Goodyear House, Old Westbury, Long Island, N. Y., 1940; view from outside looking toward living room

(figures 50 and 51 from the book of E. Mock, note 85 on p. 511, p. 43)

Fig. 51 Goodyear House (fig. 50), view from the livingroom toward the outside

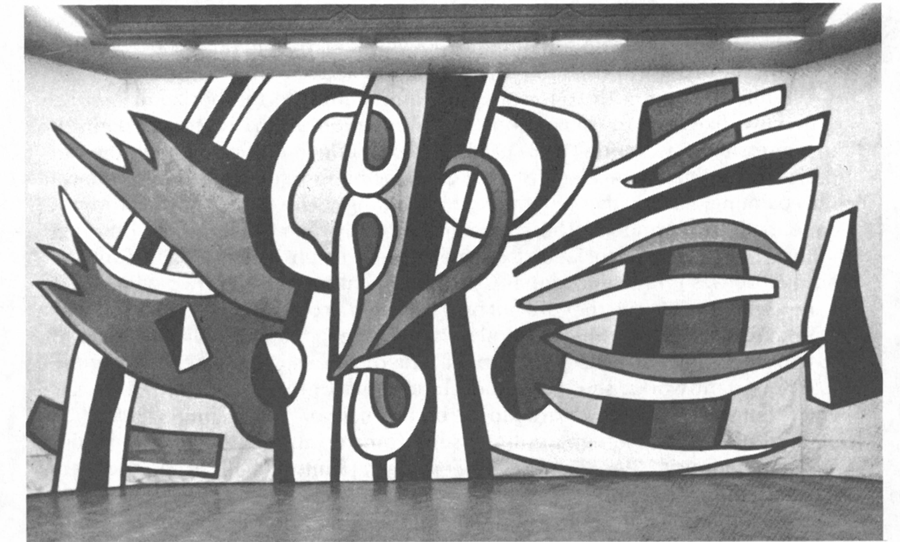

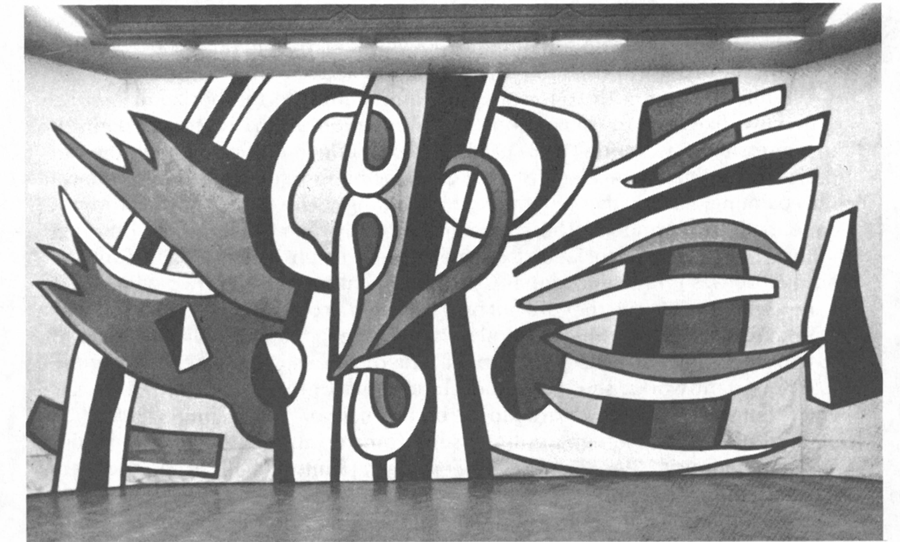

Fig. 52 Fernand Léger, “Peinture decorative” for the French Pavillion at the Trienniale, Milan, 1951

(by permission of Mr. Arnold Rüdlinger, Director of the Kunsthalle, Berne)

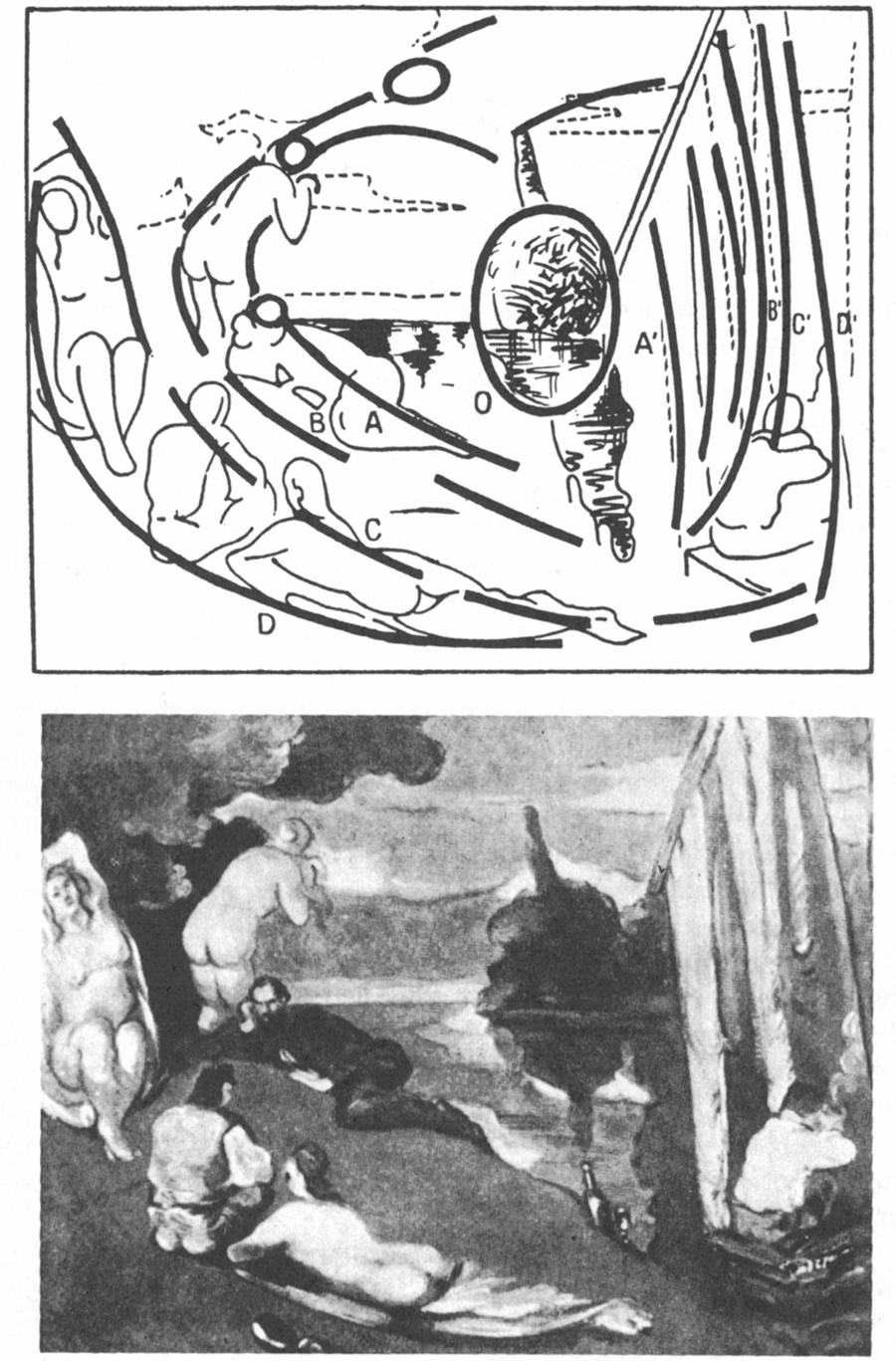

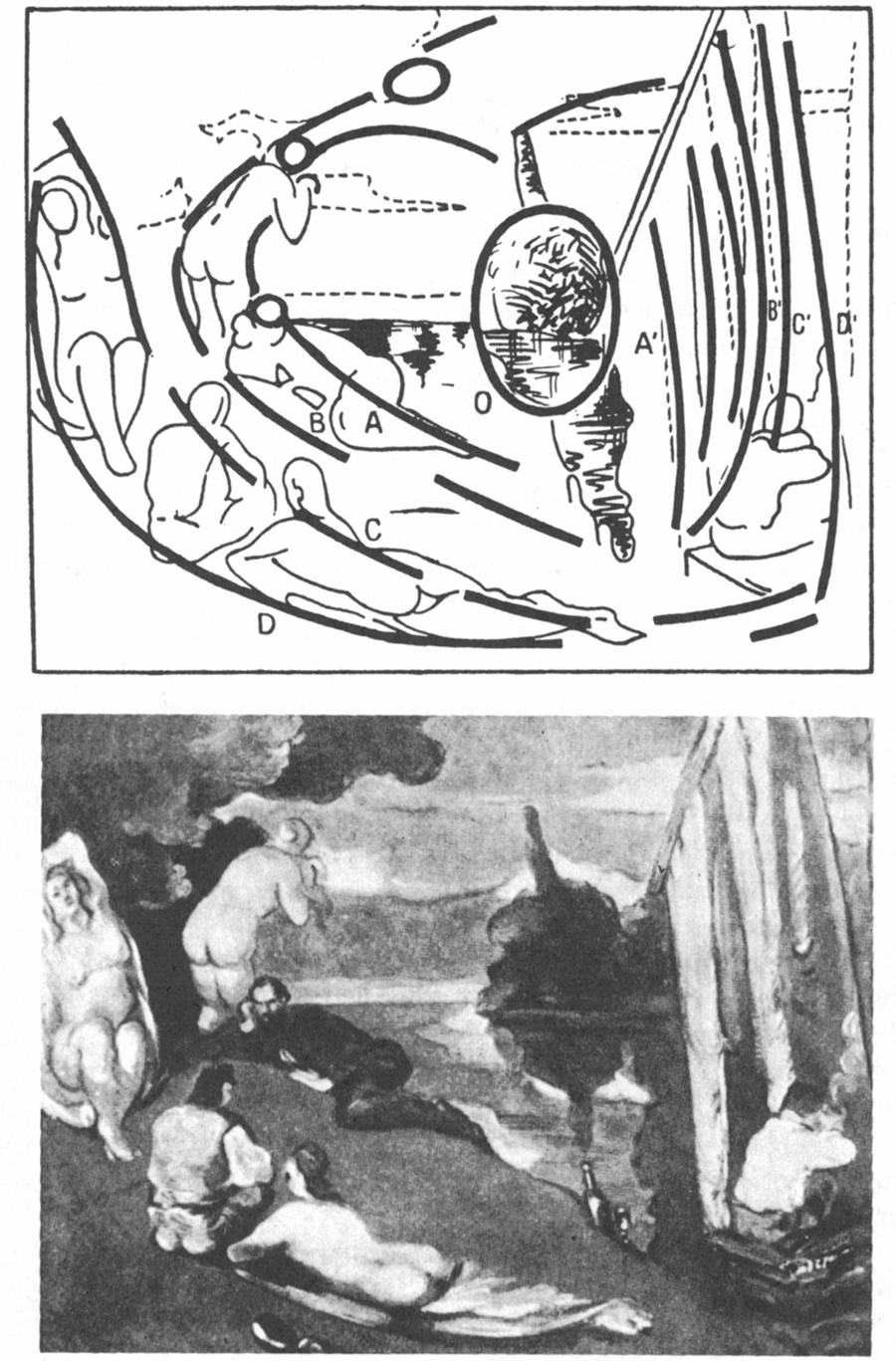

Fig. 53 Diagram for figure 54

(figures 53 and 54 from the book of L. Guerry, cited in note 16 on p. 506, p. 19)

Fig. 54 Paul Cézanne, “Don Quichotte sur les rives de Barbarie” (Don Quixote on the Barbary Coast)

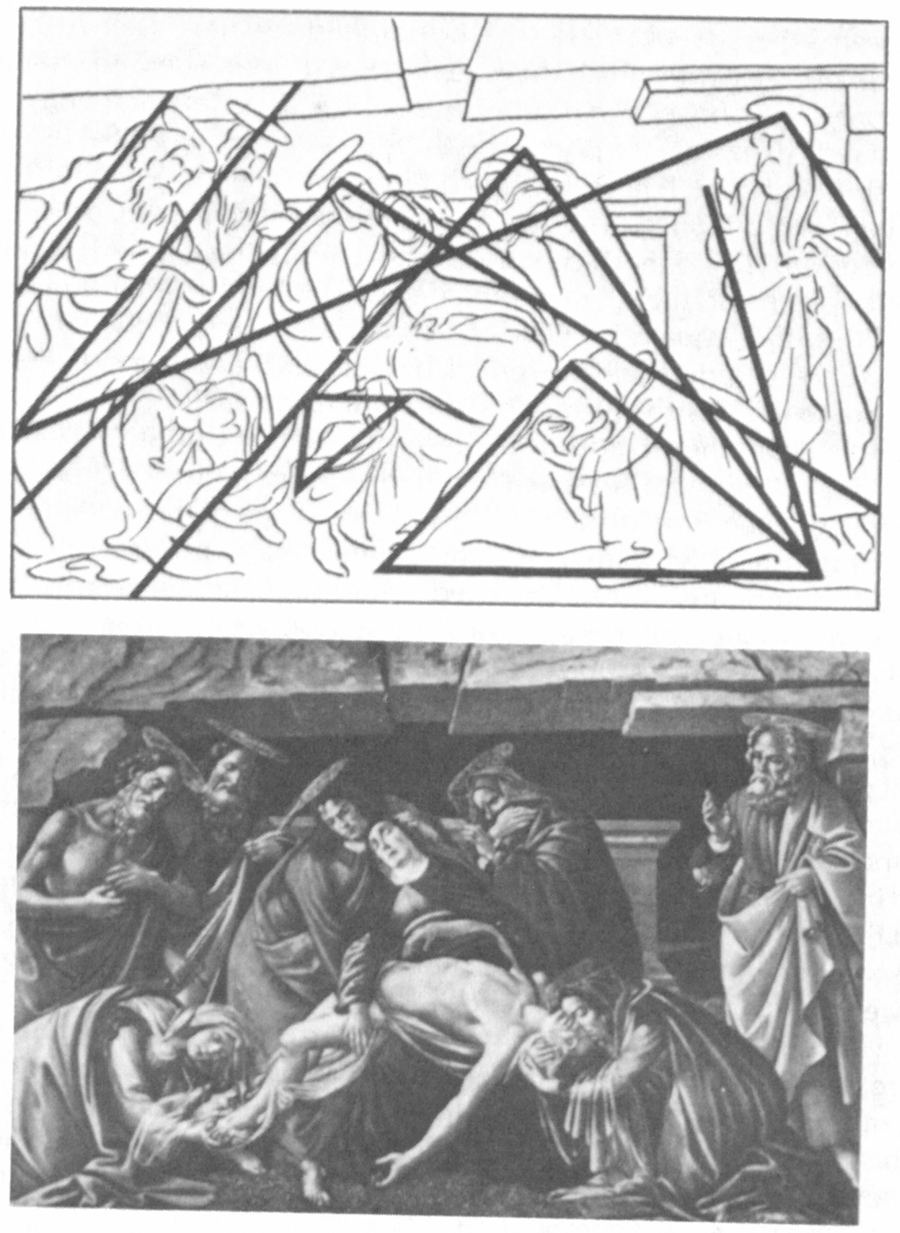

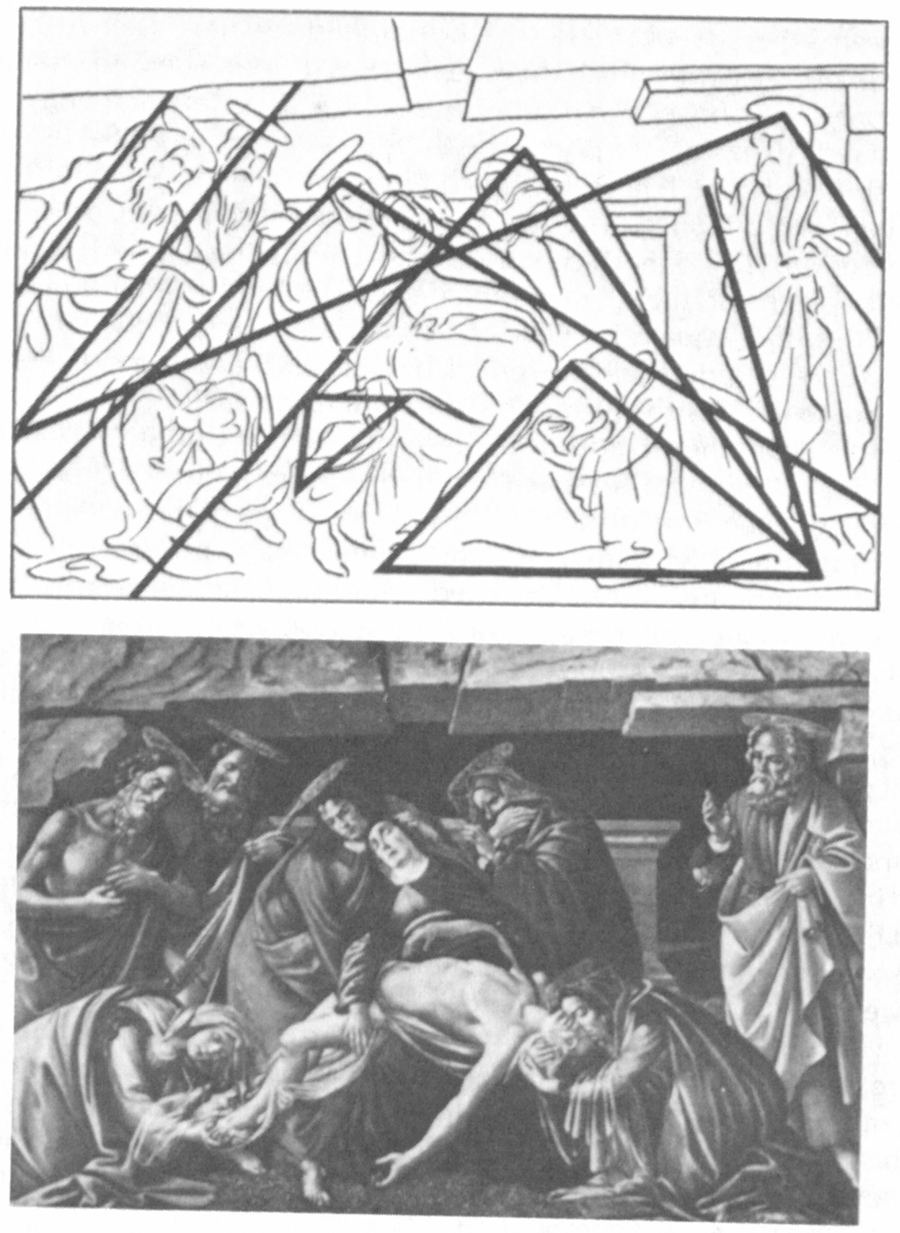

Fig. 55 Diagram for figure 56

Fig. 56 Sandro Botticelli, “Christ’s Entombment” (1605)

Fig. 57 Pablo Picasso, “The Woman of Arles,” 1913

Fig. 58 Gino Severini, “The Restless Dancer,” ca. 1912–1913

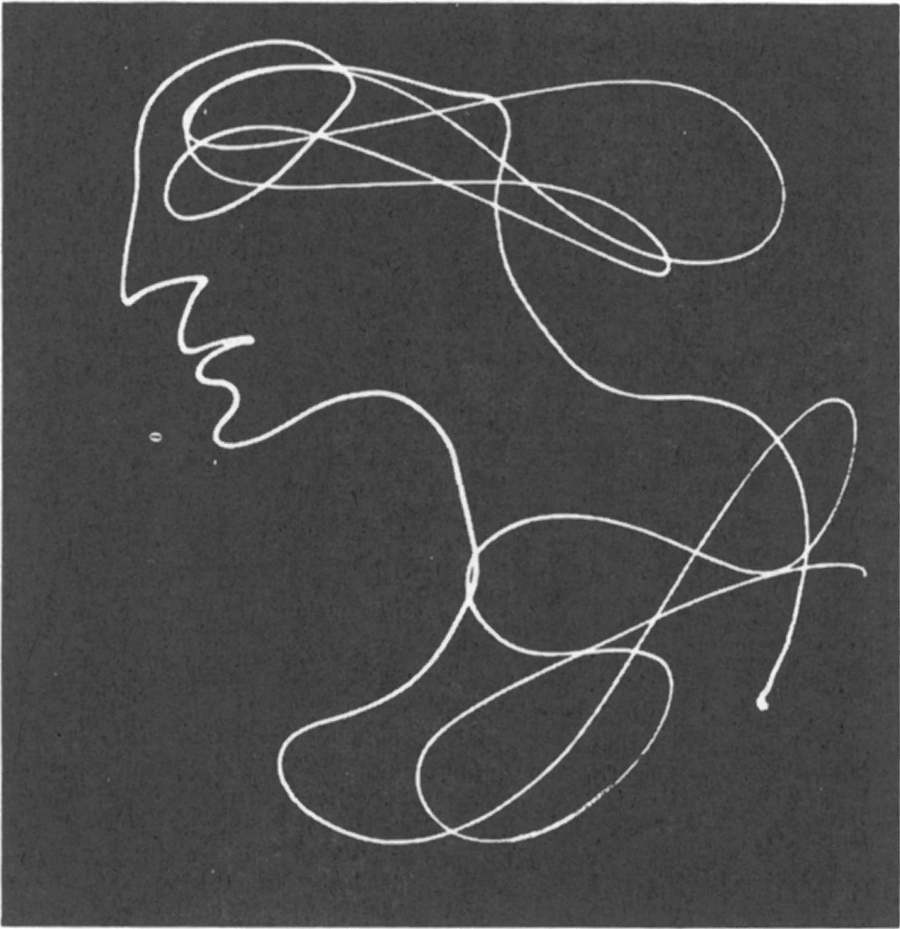

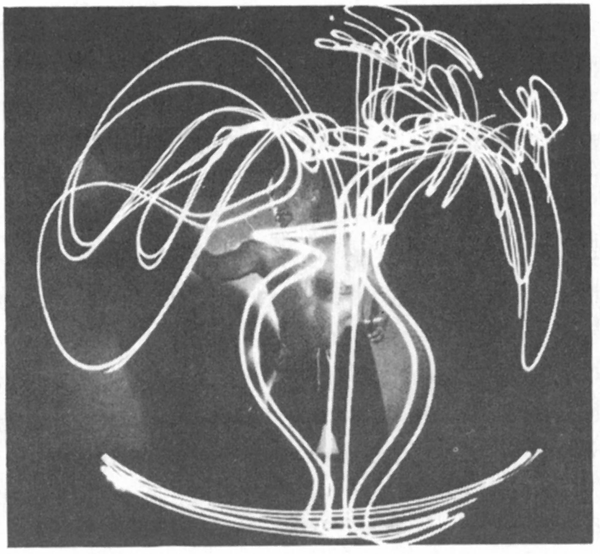

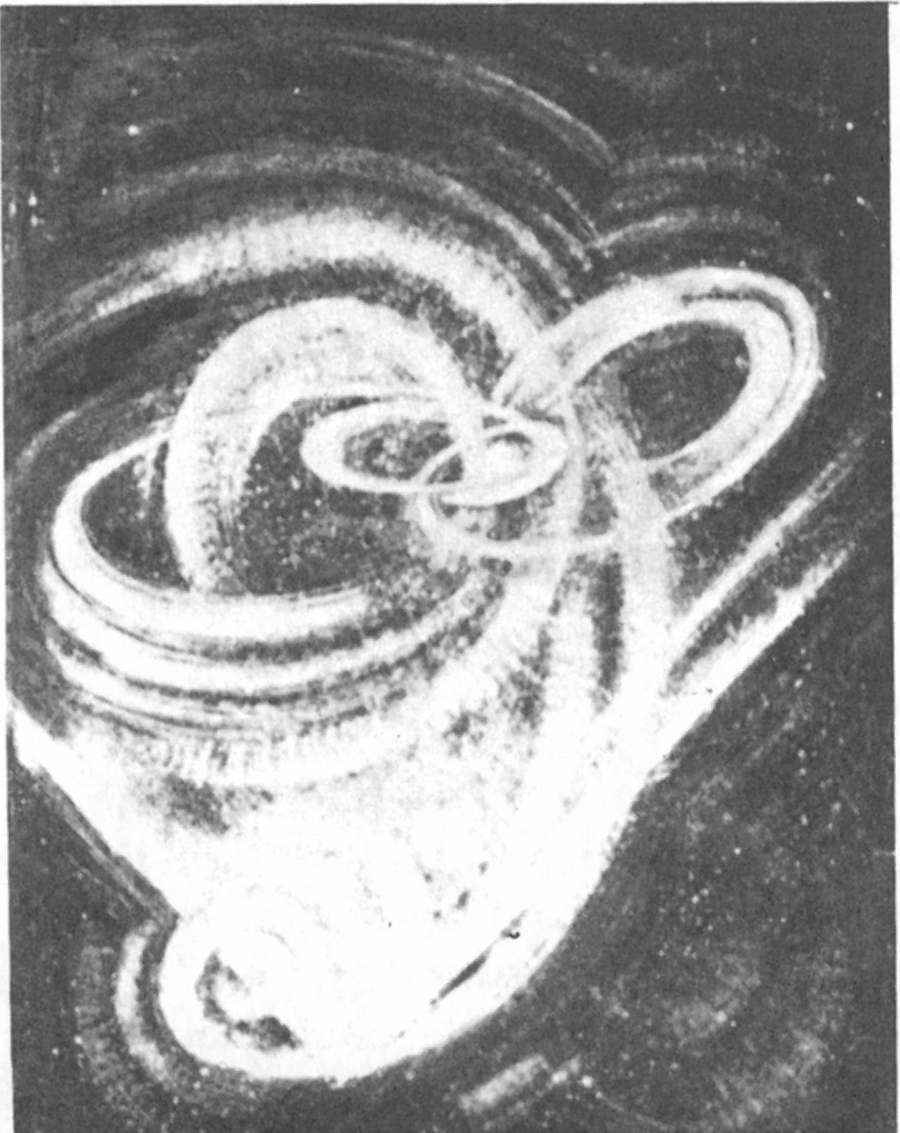

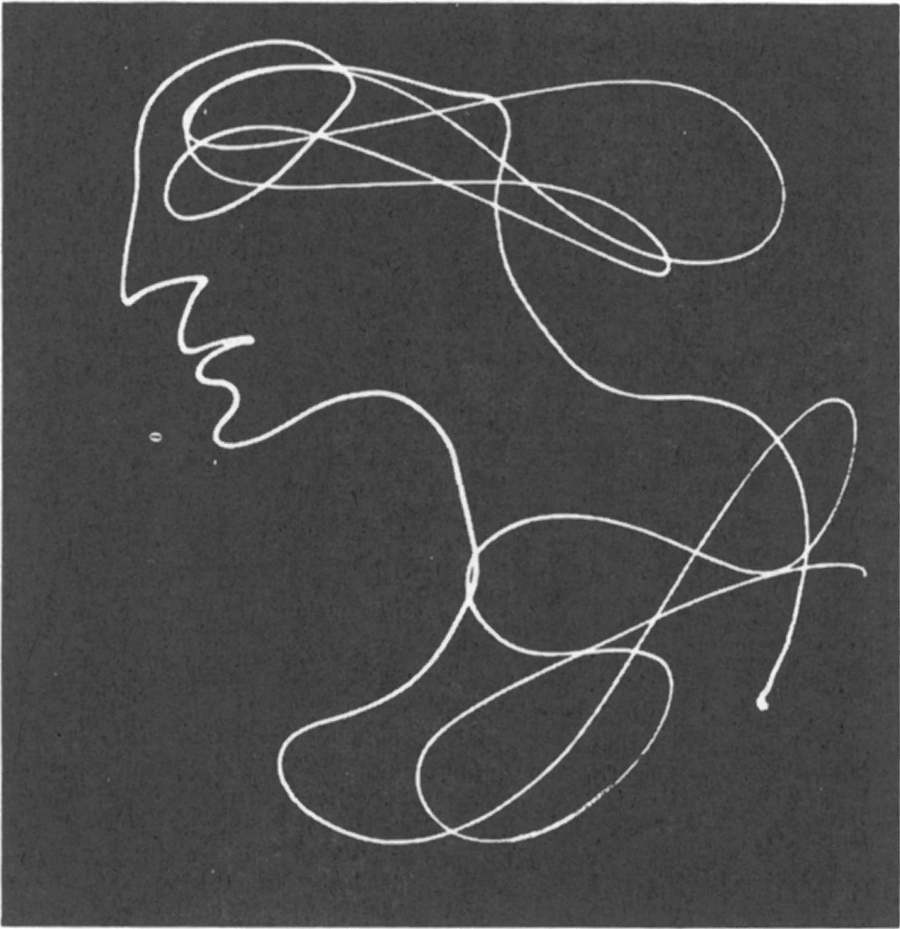

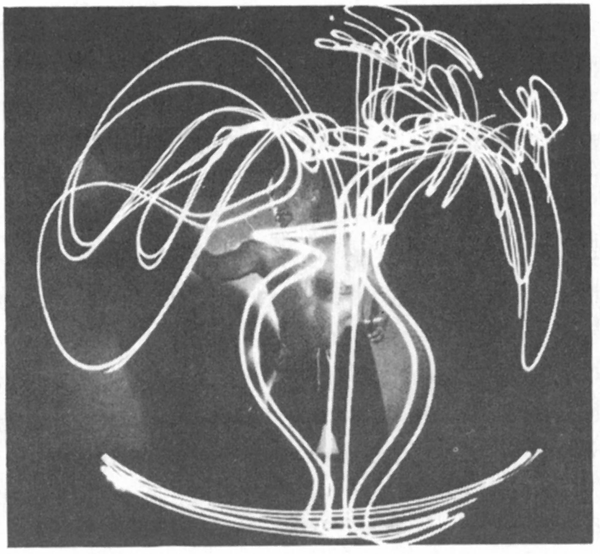

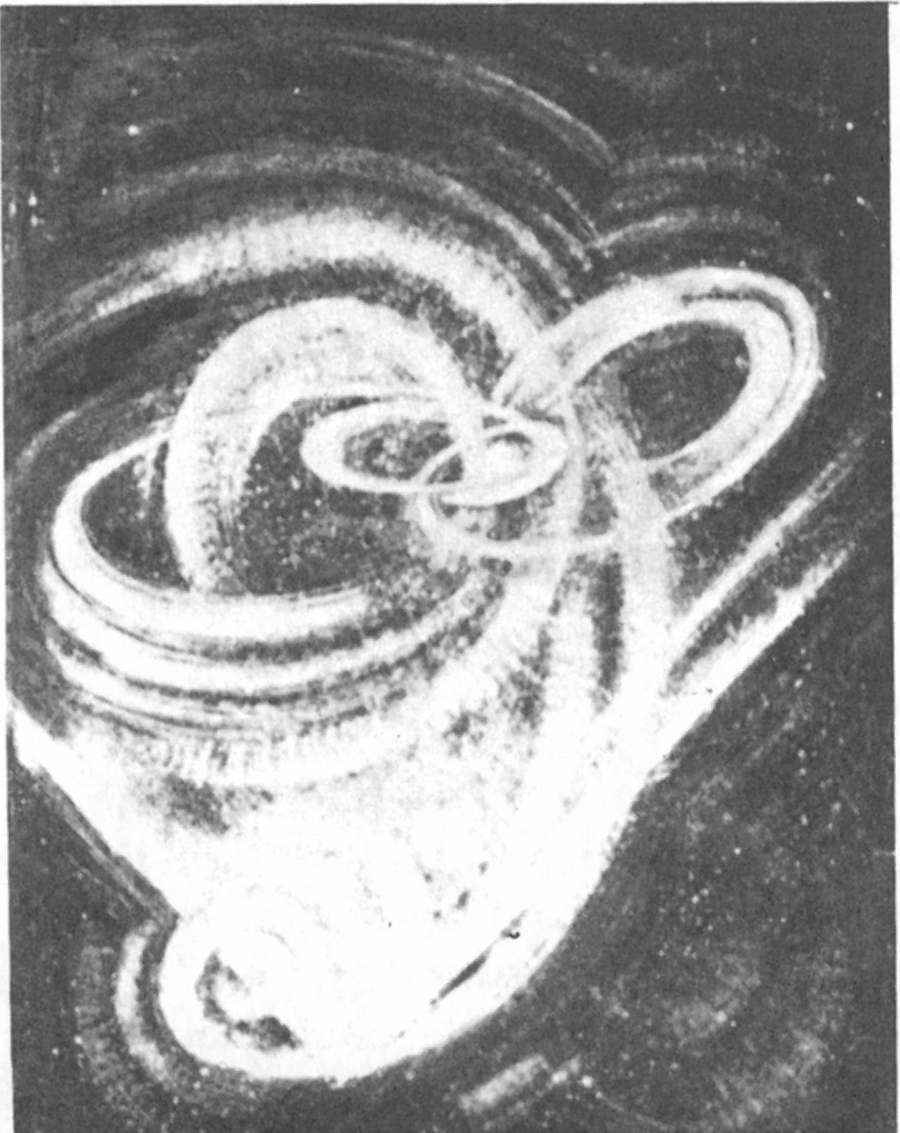

Fig. 59 Pablo Picasso, “Classic Head,” flashlight sketch, ca. 1949

(Figures 59 and 60: photographs by Gjon Mili from Life, International Edition, February 13, 1950, pp. 3 and 4, by permission of the editors)

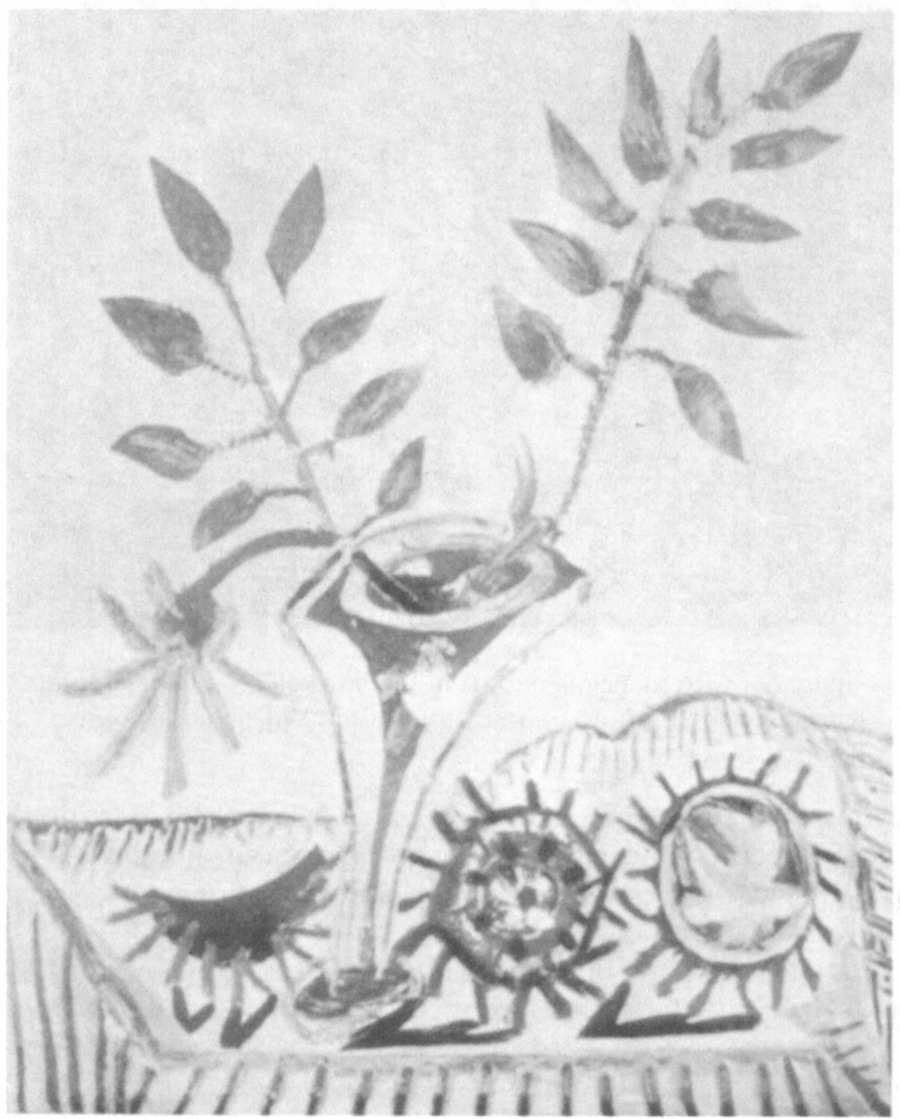

Fig. 60 Pablo Picasso, ‘“Flowers in a Vase,” flashlight sketch, ca. 1949

Fig. 61 Alexander Calder, Mobile, 1936; Collection Mrs. Meric Callery, Paris

(From James Johnson Sweeny, Alexander Calder, The Museum of Modern Art, New York, 1943, p. 32)

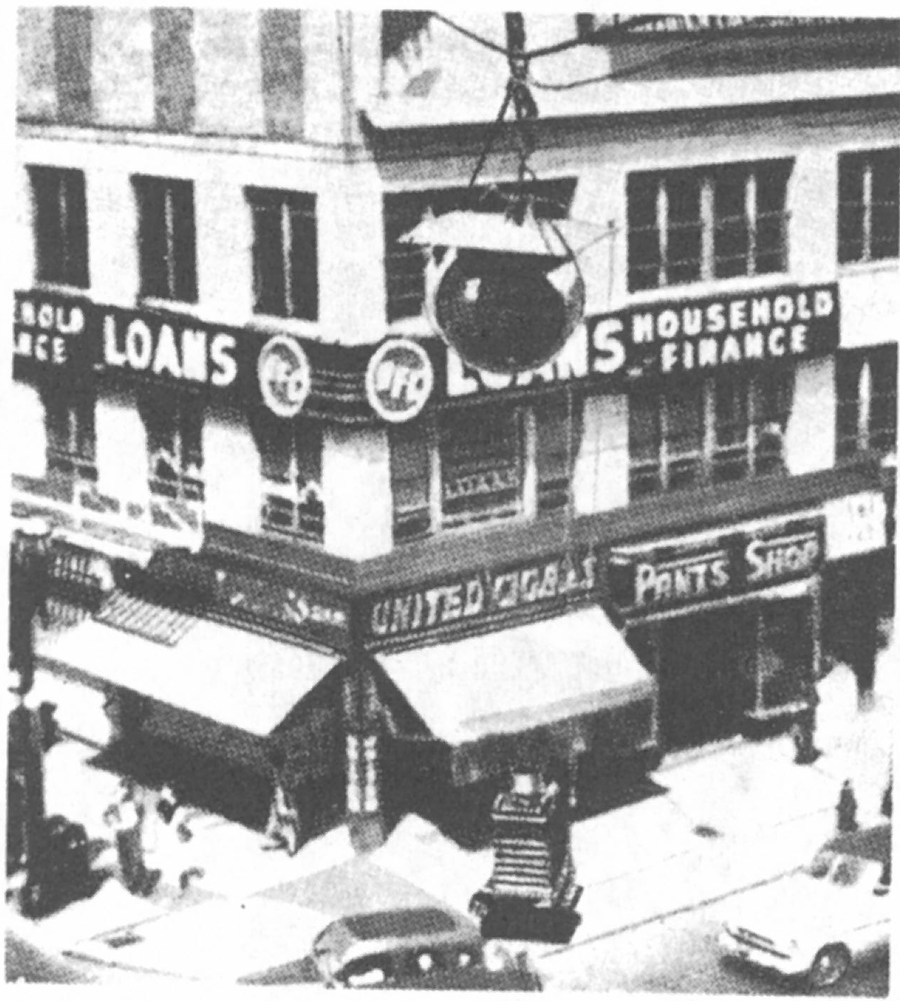

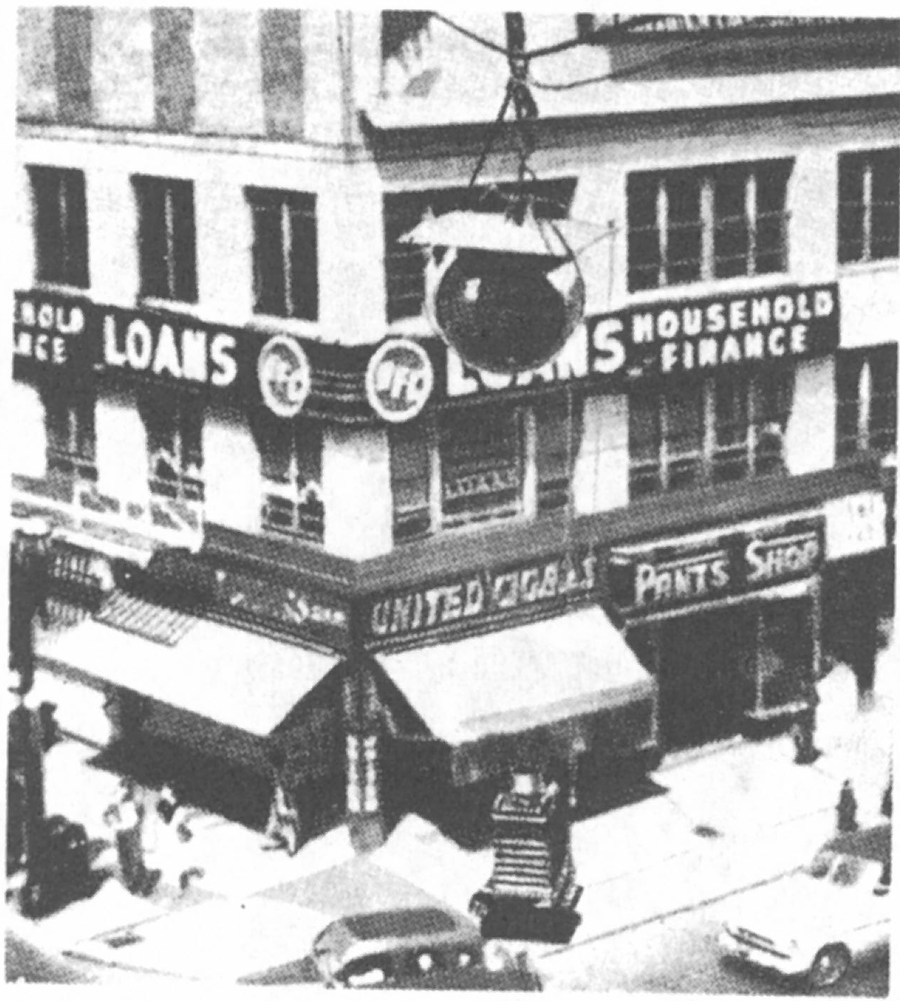

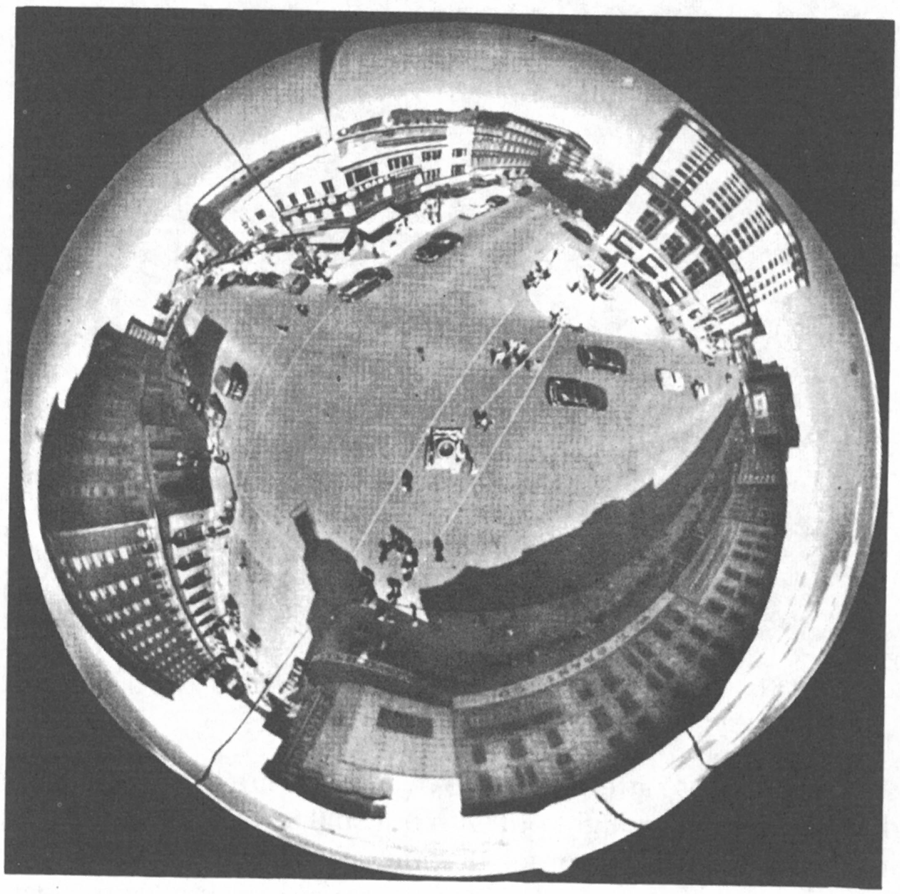

Fig. 62 View of camera and silvered sphere used to photograph figure 63

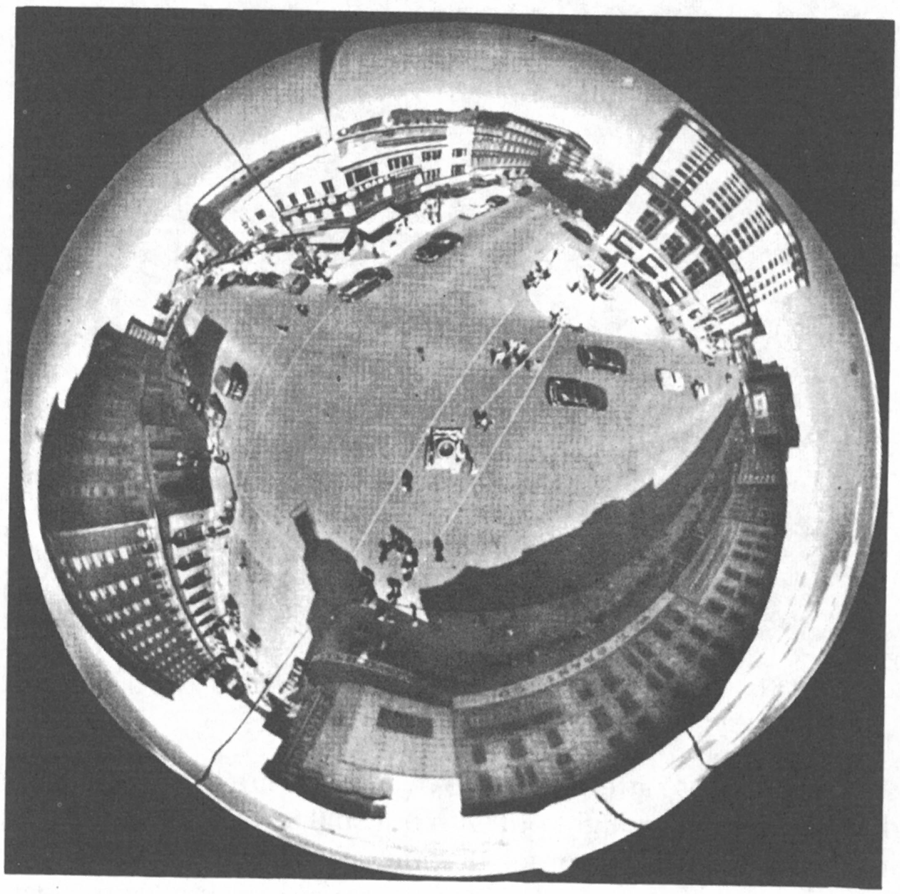

Fig. 63 Spherical photograph by Dale Rooks and John Malloy, Grand Rapids, Michigan; ca. 1949

(figure 62 and 63 from Life, International Edition, August 28, 1950, p. 2; by permission of the editors)

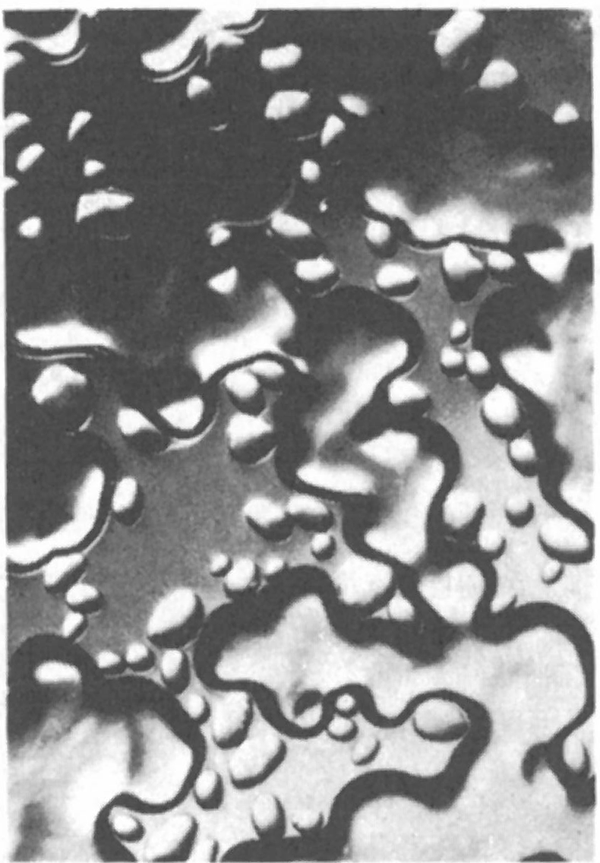

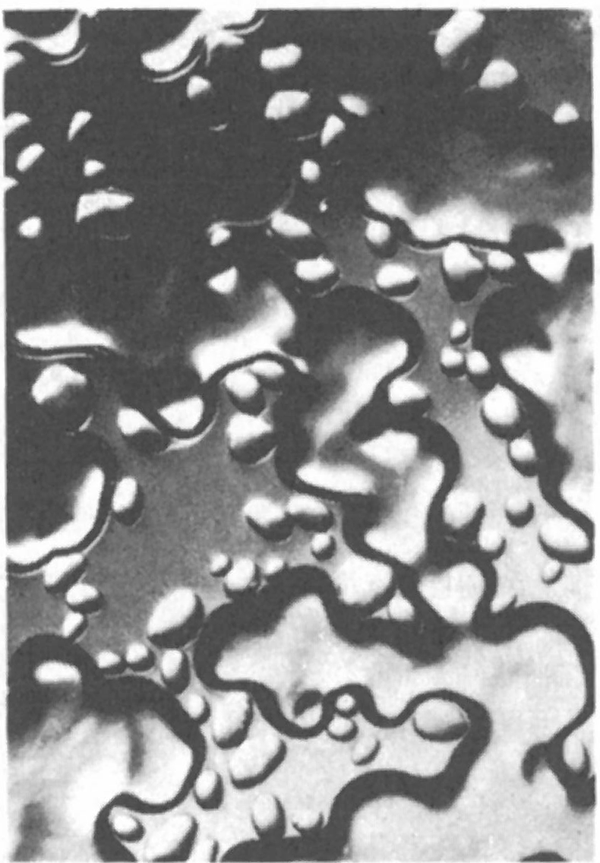

Fig. 64 Grains of starch embedded in lacquer

(Photograph by Carl Strüwe)

Fig. 65 Sophie Taeuber-Arp, “Lignes d’été,” 1942, Kunstmuseum, Basel; donation of Emanuel Hofmann

(source credits for figures 64 and 65 note 169, p. 517)

Fig. 66 Georges Braque, “Sunflowers,” 1946

(from Life, International Edition, June 6, 1949, p. 40, by permission of the editors)

Fig. 67 Hans Haffenrichter, “Energy,” egg tempera, 1954

(by permission of Hans Haffenrichter)

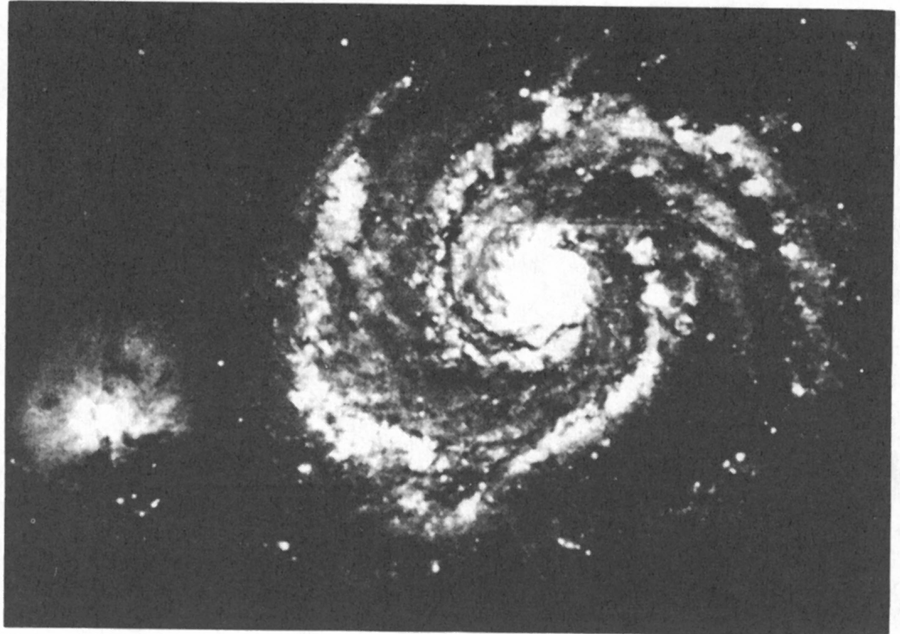

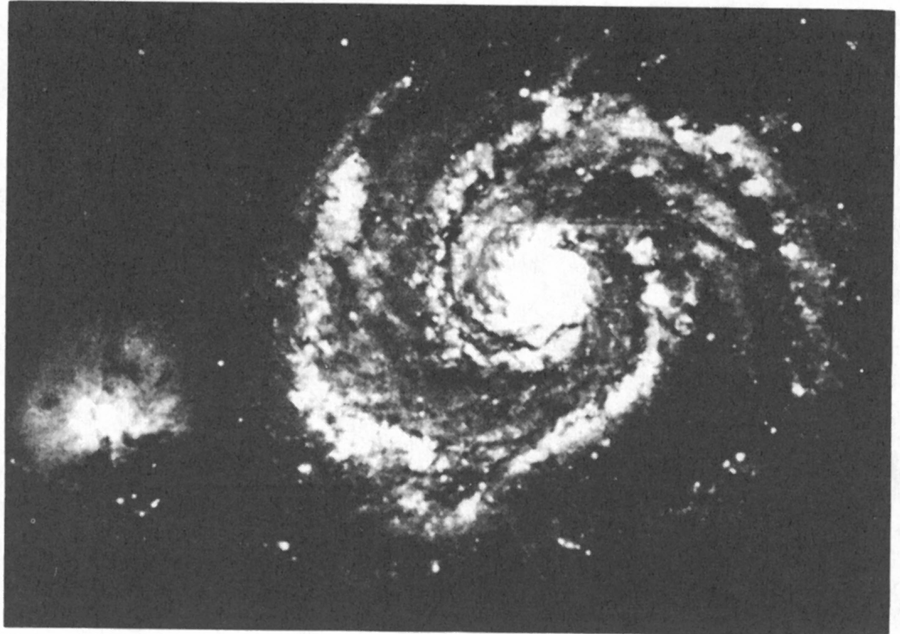

Fig. 68 Extragalactic Nebula in the Constellation “The Hounds” (canes venatici)

(From Vincent de Callatay, Goldmanns Himmelsatlas, Munich: Goldmann, 1959, p. 155, figure 5)

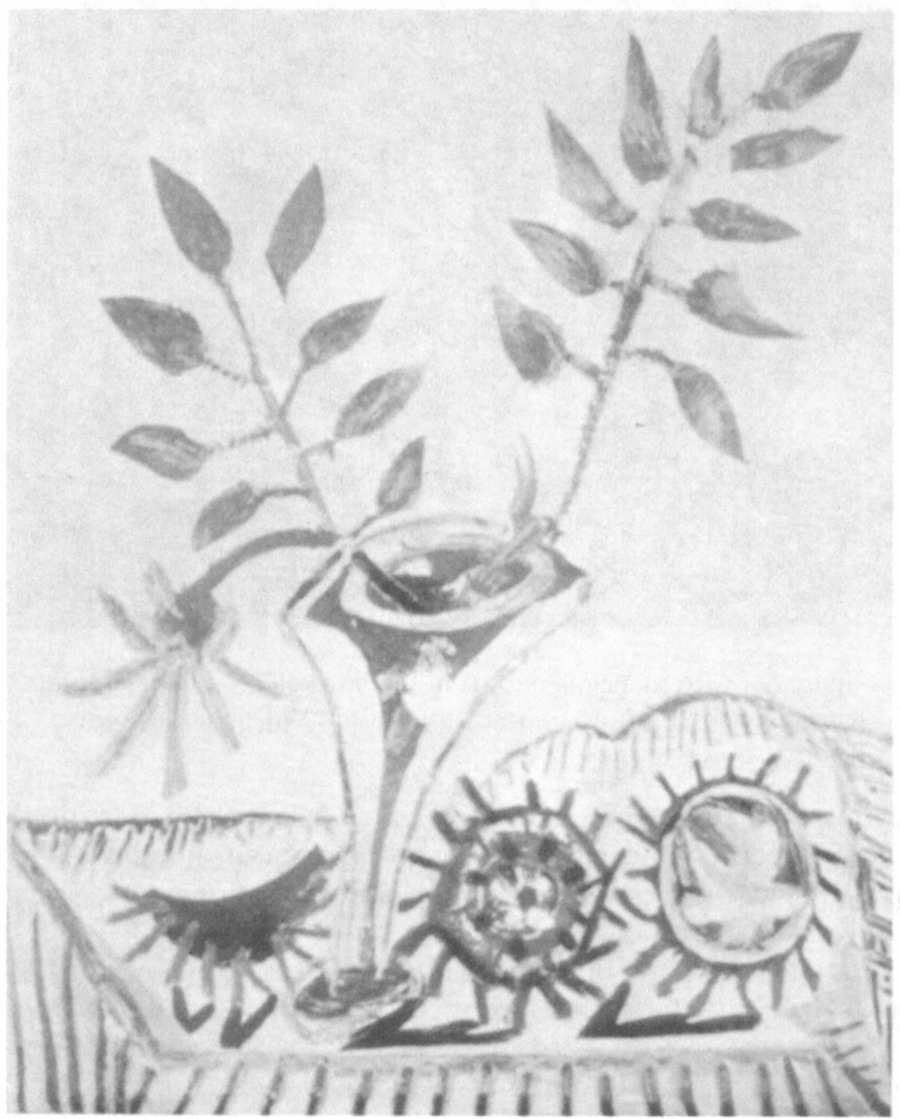

Fig. 69 Pablo Picasso, “Vase with Foliage and Sea Urchins,” 1946, Musée Grimaldi, Antibes

(From Cahiers d’Art, 23 année, Paris, 1948, no. 1, p. 43)

Preface

“Our virtues lie in the interpretation of the time.” (Shakespeare, Coriolanus, IV, 7)

“What is now proved was once only imagined.” (Blake, Proverbs of Hell)

Origin is ever-present. It is not a beginning, since all beginning is linked with time. And the present is not just the “now,” today, the moment or a unit of time. It is ever-originating, an achievement of full integration and continuous renewal. Anyone able to “concretize,” i.e., to realize and effect the reality of origin and the present in their entirety, supersedes “beginning” and “end” and the mere here and now.

The crisis we are experiencing today is not just a European crisis, nor a crisis of morals, economics, ideologies, politics or religion. It is not only prevalent in Europe and America but in Russia and the Far East as well. It is a crisis of the world and mankind such as has occurred previously only during pivotal junctures—junctures of decisive finality for life on earth and for the humanity subjected to them. The crisis of our times and our world is in a process—at the moment autonomously—of complete transformation, and appears headed toward an event which, in our view, can only be described as a “global catastrophe.” This event, understood in any but anthropocentric terms, will necessarily come about as a new constellation of planetary extent.

We must soberly face the fact that only a few decades separate us from that event. This span of time is determined by an increase in technological feasibility inversely proportional to man’s sense of responsibility—that is, unless a new factor were to emerge which would effectively overcome this menacing correlation.

It is the task of the present work to point out and give an account of this new factor, this new possibility. For if we are not successful—if we should not or cannot successfully survive this crisis by our own insight and assure the continuity of our earth and mankind in the short or the long run by a transformation (or a mutation)—then the crisis will outlive us.

Stated differently, if we do not overcome the crisis it will overcome us; and only someone who has overcome himself is truly able to overcome. Either we will be disintegrated and dispersed, or we must resolve and effect integrality. In other words, either time is fulfilled in us—and that would mean the end and death for our present earth and (its) mankind—or we succeed in fulfilling time: and this means integrality and the present, the realization and the reality of origin and presence. And it means, consequently, a transformed continuity where mankind and not man, the spiritual and not the spirit, origin and not the beginning, the present and not time, the whole and not the part become awareness and reality. It is the whole that is present in origin and originative in the present.

The remarks above are a prefatory fore-word to our exposition. The book is addressed to each and every one, particularly to those who live knowledge, and not just to those who create it. Our exposition is neither a monologue nor a postulate but a discussion—an intent the author has striven to convey by using the stylistic device of “we” and by including others in the discussion via Extensive quotations.

The conception of this work dates from 1932. Any conception, however, is a personal view whose evidential character is valid only for the individual. During the seventeen years since the basic conception was formed, the author has encountered statements here and there in the literature of the numerous subjects treated herein that in part resemble, relate or correspond to aspects of his basic understanding. The quotations and references to such sources are intended to lend a generally valid evidential character to the personal validity of the original conception. In this the author hopes to fulfil the ethical imperative of presenting an expository dialogue instead of a postulatory monologue and thereby convey the probable objective correctness of the basic idea rather than merely a subjective opinion of its correctness.

For this opportunity of being able to express my appreciation, I gratefully acknowledge the aid of my friends and all who have contributed to the success of this venture. My special thanks to Mrs. Gertrud and Mr. Walter R. Diethelm (Zürich-Zollikon), and particularly to Dr. Franz Meyer (Zürich); without their assistance and trust, I would have been unable to carry out the difficult and extended task amidst my economically precarious circumstances.

My gratitude also to the following for permission to reproduce several rare illustrations: The British Museum, London; Messrs. Kegan Paul, Trench, Trubner & Co., London; Hybernia Verlag, Basel; Galerie Rosenberg, Paris; Galerie Gasser, Zürich; and the Kunsthalle, Berne.

Burgdorf (Canton Berne); Whitsuntide 1949

Jean Gebser

From the Preface to the Second Edition

The present work has been out of print for four years, as other pressing obligations have frequently interrupted the author’s preparation of this new edition. . . . The text has been revised only where necessary for reasons of style, and where excision of repetitive material and minor rearrangement seemed advisable. Apart from this, the original version has been altered only by the addition of supplementary material and by a substantial increase in the number of illustrations. The additions to the text are written in such a way as to be immediately recognizable, and many have been incorporated into the notes so as not to unduly encumber the text.

The additions have been necessary in the light of many ominous as well as encouraging events since publication of the first edition. The ominous aspects are conceivably outweighed and counterbalanced by insights and achievements which, by virtue of their spiritual potency, cannot remain without effect.

Among these achievements, the writings of Sri Aurobindo and Pierre Teilhard de Chardin are pre-eminent. . . . Both develop in their own way the conception of a newly emergent consciousness which Sri Aurobindo has designated as the “supramental.” We defined it in turn as the “aperspectival (arational-integral)’’ consciousness to which we first referred in Rilke and Spain (Rilke und Spanien, Zürich/New York: Oprecht, 1940) and later in our Transformation of the Occident (1943). It remains the principal concern of the present work to elucidate the possibility as well as the emergence of this new consciousness, and to describe its uniqueness. This same concern is also evident in the author’s later works Standing the Test, or Verifications of the New Consciousness (2nd ed., 1969) and Asian Primer (1962).

The reader will have to judge for himself in what respects our discussion parallels or diverges from those of the authors mentioned, the dissimilarities being occasioned by the differing points of departure. Although both authors have a human-universal orientation, Sri Aurobindo—integrating Western thought—proceeds from a reformed Hindu, Teilhard de Chardin from a Catholic position, whereas the present work is written from a general and Occidental standpoint. But this does not preclude the one exposition from not merely supporting and complementing, but also corroborating the others.

Our exposition has been further corroborated by many scientific disciplines and by the arts. The results of research, the discoveries, insights and creations of numerous creative individuals testify to an attitude closely akin to our own. Not all of these could be considered in our discussion, and we have mentioned only those that seemed to us most significant. The references to these complementary sources may be considered a not insignificant enhancement of this revised version.

There remains the pleasant task of thanking those whose aid has contributed to the success of this edition. I am particularly grateful to the Werner Reimers Foundation for Anthropogenetic Research and its director Prof. Dr. Helmut de Terra (Frankfurt/M.), whose support enabled me to devote myself for a time exclusively to final revisions for this edition. I am equally grateful to Dr. Heinz Temming (Gluckstadt) for his extensive assistance in correcting the proofs and compiling the indexes. In conclusion, my thanks to Editions Gallimard (Paris) and Editions de Vischer (Rhode-St.-Genèse) for permission to reproduce several illustrations.

Berne, February 1966

Jean Gebser

From the Preface to the Paperbound Edition

The present work was written primarily for my generation, or so I thought; but the interest shown by the younger generation has become increasingly evident. The principal subject of the book, proceeding from man’s altered relationship to time, is the new consciousness, and to this those of the younger generation are keenly attuned. I am particularly pleased that this edition will make the book more accessible to them. . . .

I would like to thank my wife and my friend Dr. Rolf Renker (Düren) for their invaluable assistance in the preparation of this paperbound edition.

Wabern/Berne, February 1973

Jean Gebser

PART ONE:

Foundations of the Aperspectival World

A Contribution to the History of the Awakening of Consciousness

Editorial Note Regarding the Annotations

Besides references to sources and the relevant secondary literature, the extensive notes following each chapter contain important supplementary information (commentaries and digressions to extend and clarify the questions under discussion). Reference to this supplementary information is made throughout the text by italicized, raised numbers in order to distinguish them from the mere source references.

[In the notes themselves, an asterisk following the number indicates a change or emendation for the English edition. These changes are in almost all instances the substitution of quotations and their accompanying source references for passages originally in English, or for quotations familiar from existing English translations. In one or two instances a clarifying remark has been added.

References to the author’s own works have been brought up to date by including in each instance volume and page numbers of the complete edition of his works in the original (Jean Gebser, Gesamtausgabe, Schaffhausen, Switzerland, 1975–1981, eight volumes and index).

The author has placed particular emphasis on cross-referencing the notes and source references. Accordingly, his arrangement, although departing from current scholarly practice, has been retained in this English edition. The notes, however, have been placed at the end of each chapter, rather than in a separate volume, as is the case with the second through fifth editions of the original.—Translators note.]

1

Fundamental Considerations

Anyone today who considers the emergence of a new era of mankind as a certainty and expresses the conviction that our rescue from collapse and chaos could come about by virtue of a new attitude and a new formation of man’s consciousness, will surely elicit less credence than those who have heralded the decline of the West. Contemporaries of totalitarianism, World War II, and the atom bomb seem more likely to abandon even their very last stand than to realize the possibility of a transition, a new constellation or a transformation, or even to evince any readiness to take a leap into tomorrow, although the harbingers of tomorrow, the evidence of transformation, and other signs of the new and imminent cannot have gone entirely unnoticed. Such a reaction, the reaction of a mentality headed for a fall, is only too typical of man in transition.

The present book is, in fact, the account of the nascence of a new world and a new consciousness. It is based not on ideas or speculations but on insights into mankind’s mutations from its primordial beginnings up to the present—on perhaps novel insights into the forms of consciousness manifest in the various epochs of mankind: insights into the powers behind their realization as manifest between origin and the present, and active in origin and the present. And as the origin before all time is the entirety of the very beginning, so too is the present the entirety of everything temporal and time-bound, including the effectual reality of all time phases: yesterday, today, tomorrow, and even the pre-temporal and timeless.

The structuration we have discovered seems to us to reveal the bases of consciousness, thereby enabling us to make a contribution to the understanding of man’s emergent consciousness. It is based on the recognition that in the course of mankind’s history—and not only Western man’s—clearly discernable worlds stand out whose development or unfolding took place in mutations of consciousness. This, then, presents the task of a cultural-historical analysis of the various structures of consciousness as they have proceeded from the various mutations.

For this analysis we shall employ a method of demonstrating the respective consciousness structures of the various “epochs” on the basis of their representative evidence and their unique forms of visual as well as linguistic expression. This approach, which is not limited to the currently dominant mentality, attempts to present in visible, tangible, and audible form the respective consciousness structures from within their specific modalities and unique constitutions by means appropriate to their natures.

By returning to the very sources of human development as we observe all of the structures of consciousness, and moving from there toward our present day and our contemporary situation and consciousness, we can not only discover the past and the present moment of our existence but also gain a view into the future which reveals the traits of a new reality amidst the decline of our age.

It is our belief that the essential traits of a new age and a new reality are discernible in nearly all forms of contemporary expression, whether in the creations of modern art, or in the recent findings of the natural sciences, or in the results of the humanities and sciences of the mind. Moreover we are in a position to define this new reality in such a way as to emphasize one of its most significant elements. Our definition is a natural corollary of the recognition that man’s coming to awareness is inseparably bound to his consciousness of space and time.

Scarcely five hundred years ago, during the Renaissance, an unmistakable reorganization of our consciousness occurred: the discovery of perspective which opened up the three-dimensionality of space.1 This discovery is so closely linked with the entire intellectual attitude of the modern epoch that we have felt obliged to call this age the age of perspectivity and characterize the age immediately preceding it as the “unperspectival” age. These definitions, by recognizing a fundamental characteristic of these eras, lead to the further appropriate definition of the age of the dawning new consciousness as the “aperspectival” age, a definition supported not only by the results of modern physics, but also by developments in the visual arts and literature, where the incorporation of time as a fourth dimension into previously spatial conceptions has formed the initial basis for manifesting the “new.”

“Aperspectival” is not to be thought of as merely the opposite or negation of “perspectival”; the antithesis of “perspectival” is “unperspectival.” The distinction in meaning suggested by the three terms unperspectival, perspectival, and aperspectival is analogous to that of the terms illogical, logical, and alogical or immoral, moral, and amoral.2 We have employed here the designation “aperspectival” to clearly emphasize the need of overcoming the mere antithesis of affirmation and negation. The so-called primal words (Urworte), for example, evidence two antithetic connotations: Latin altus meant “high” as well as “low”; sacer meant “sacred” as well as “cursed.” Such primal words as these formed an undifferentiated psychically-stressed unity whose bivalent nature was definitely familiar to the early Egyptians and Greeks.3 This is no longer the case with our present sense of language; consequently, we have required a term that transcends equally the ambivalence of the primal connotations and the dualism of antonyms or conceptual opposites.

Hence we have used the Greek prefix “a-” in conjunction with our Latin-derived word “perspectival” in the sense of an alpha privativum and not as an alpha negativum, since the prefix has a liberating character (privativum, derived from Latin privare, i.e., “to liberate”). The designation “aperspectival,” in consequence, expresses a process of liberation from the exclusive validity of perspectival and unperspectival, as well as pre-perspectival limitations. Our designation, then, does not attempt to unite the inherently coexistent unperspectival and perspectival structures, nor does it attempt to reconcile or synthesize structures which, in their deficient modes, have become irreconcilable. If “aperspectival” were to represent only a synthesis it would imply no more than “perspectival-rational” and would be limited and only momentarily valid, inasmuch as every union is threatened by further separation. Our concern is with integrality and ultimately with the whole; the word “aperspectival” conveys our attempt to deal with wholeness. It is a definition which differentiates a perception of reality that is neither perspectivally restricted to only one sector nor merely unperspectivally evocative of a vague sense of reality.

Finally, we would emphasize the general validity of the term “aperspectival”; it is definitely not intended to be understood as an extension of concepts used in art history and should not be so construed. When we introduced the concept in 1936/1939, it was within the context of scientific as well as artistic traditions.4 The perspectival structure as fully realized by Leonardo da Vinci is of fundamental importance not only to our scientific-technological but also artistic understanding of the world. Without perspective neither technical drafting nor three-dimensional painting would have been possible. Leonardo—scientist, engineer, and artist in one—was the first to fully develop drafting techniques and perspectival painting. In this same sense, that is from a scientific as well as artistic standpoint, the term “aperspectival” is valid, and the basis for this significance must not be overlooked, for it legitimizes the validity and applicability of the term to the sciences, the humanities, and the arts.

It is our intent to furnish evidence that the aperspectival world, whose nascence we are witnessing, can liberate us from the superannuated legacy of both the unperspectival and the perspectival worlds. In very general terms we might say that the unperspectival world preceded the world of mind- and ego-bound perspective discovered and anticipated in late antiquity and first apparent in Leonardo’s application of it. Viewed in this manner the unperspectival world is collective, the perspectival individualistic. That is, the unperspectival world is related to the anonymous “one” or the tribal “we,” the perspectival to the “I” or Ego; the one world is grounded in Being, the other, beginning with the Renaissance, in Having; the former is predominantly irrational, the later rational.

Today, at least in Western civilization, both modes survive only as deteriorated and consequently dubious variants. This is evident from the sociological and anthropological questions currently discussed in the Occidental forum; only questions that are unresolved are discussed with the vehemence characteristic of these discussions. The current situation manifests on the one hand an egocentric individualism exaggerated to extremes and desirous of possessing everything, while on the other it manifests an equally extreme collectivism that promises the total fulfillment of man’s being. In the latter instance we find the utter abnegation of the individual valued merely as an object in the human aggregate; in the former a hyper-valuation of the individual who, despite his limitations, is permitted everything. This deficient, that is destructive, antithesis divides the world into two warring camps, not just politically and ideologically, but in all areas of human endeavor.

Since these two ideologies are now pressing toward their limits we can assume that neither can prevail in the long run. When any movement tends to the extremes it leads away from the center or nucleus toward eventual destruction at the outer limits where the connections to the life-giving center finally are severed. It would seem that today the connections are already broken, for it is increasingly evident that the individual is being driven into isolation while the collective degenerates into mere aggregation. These two conditions, isolation and aggregation, are in fact clear indications that individualism and collectivism have now become deficient.

When we have grasped this it is at once apparent that we can extricate ourselves from our dangerous situation only by ordering our relationships to ourselves, to our “I” or Ego, and not just our relationships with others, to the “Thou,” that is to God, the world, our fellow man and neighbor. That seems possible only if we are willing to assimilate the entirety of our human existence into our awareness. This means that all of our structures of awareness that form and support our present consciousness structure will have to be integrated into a new and more intensive form, which would in fact unlock a new reality. To that end we must constantly relive and re-experience in a decisive sense the full depth of our past. The adage that anyone who denies and condemns his past also abnegates his future is valid for the individual as well as for mankind. Our plea for an appropriate ordering and conscious realization of our relationships to the “I” as well as the “Thou” chiefly concerns the ordering and conscious recognition of our origin, and of all factors leading to the present. It is only in terms of man in his entirety that we shall achieve the necessary detachment from the present situation, i.e., from both our unperspectival ties to the group or collective, and our perspectival attachment to the separated, individual Ego. When we become aware of the exhausted residua of past or passing forms of our understanding of reality we will recognize more clearly the signs of the inevitable “new.” We will also sense that there are new sources which can be tapped: the sources of the aperspectival world that can liberate us from the two exhausted and deficient forms which have become almost completely invalid and are certainly no longer all-inclusive or decisive.

It is our task in this book to work out this aperspectival basis. Our discussion will rely more on the evidence presented in the history of thought than on the findings of the natural sciences as is the case with the author’s Transformation of the Occident. Among the disciplines of historical thought the investigation of language will form the predominant source of our insight since it is the pre-eminent means of reciprocal communication between man and the world.

It is not sufficient for us to merely furnish a postulate; rather, it will be necessary to show the latent possibilities in us and in our present, possibilities that are about to become acute, that is, effectual and consequently real. In the following discussion we shall therefore proceed from two basic considerations:

1. A mere interpretation of our times is inadequate. We must furnish concrete evidence of phenomena that are clearly revealed as being new and that transform not only our countenance, but the very countenance of time.

2. The condition of today’s world cannot be transformed by technocratic rationality, since both technocracy and rationality are apparently nearing their apex; nor can it be transcended by preaching or admonishing a return to ethics and morality, or in fact, by any form of return to the past.

We have only one option: in examining the manifestations of our age, we must penetrate them with sufficient breadth and depth that we do not come under their demonic and destructive spell. We must not focus our view merely on these phenomena, but rather on the humus of the decaying world beneath, where the seedlings of the future are growing, immeasurable in their potential and vigor. Since our insight into the energies pressing toward development aids their unfolding, the seedlings and inceptive beginnings must be made visible and comprehensible.

It will be our task to demonstrate that the first stirrings of the new can be found in all areas of human expression, and that they inherently share a common character. This demonstration can succeed only if we have certain knowledge about the manifestations of both our past and our present. Consequently, the task of the present work will be to work out the foundations of the past and the present which are also the basis of the new consciousness and the new reality arising therefrom. It will be the task of the second part to define the new emergent consciousness structure to the extent that its inceptions are already visible.

We shall therefore begin with the evidence and not with idealistic constructions; in the face of present-day weapons of annihilation, such constructions have less chance of survival than ever before. But as we shall see, weapons and nuclear fission are not the only realities to be dealt with; spiritual reality in its intensified form is also becoming effectual and real. This new spiritual reality is without question our only security that the threat of material destruction can be averted. Its realization alone seems able to guarantee man’s continuing existence in the face of the powers of technology, rationality, and chaotic emotion. If our consciousness, that is, the individual person’s awareness, vigilance, and clarity of vision, cannot master the new reality and make possible its realization, then the prophets of doom will have been correct. Other alternatives are an illusion; consequently, great demands are placed on us, and each one of us have been given a grave responsibility, not merely to survey but to actually traverse the path opening before us.

There are surely enough historical instances of the catastrophic downfall of entire peoples and cultures. Such declines were triggered by the collision of deficient and exhausted attitudes that were insufficient for continuance with those more recent, more intense and, in some respects, superior. One such occurrence vividly exemplifies the decisive nature of such crises: the collision of the magical, mythical, and unperspectival culture of the Central American Aztecs with the rational-technological, perspectival attitude of the sixteenth-century Spanish conquistadors. A description of this event can be found in the Aztec chronicle of Frey Bernardino de Sahagun, written eight years after Cortez’ conquest of Mexico on the basis of Aztec accounts. The following excerpt forms the beginning of the thirteenth chapter of the chronicle which describes the conquest of Mexico City:

The thirteenth chapter, wherein is recounted

how the Mexican king Montezuma

sends other sorcerers

who were to cast a spell on the Spanish

and what happened to them on the way.

And the second group of messengers—

the soothsayers, the magicians, and the high priests—

likewise went to receive the Spanish.

But it was to no avail;

they could not bewitch the people,

they could not reach their intent with the Spanish;

they simply failed to arrive.5